Evils of the heaths and deserts: a barren land swarming with monsters

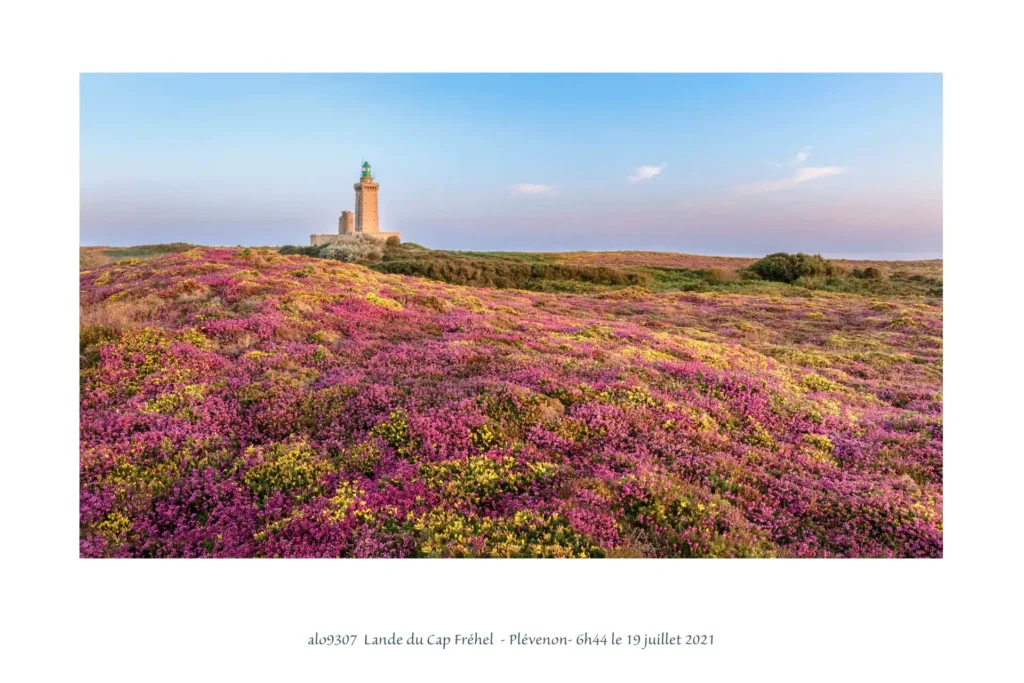

1. Origins of the moorlands

The heaths, with their desolate appearance and vast stretches of heather, have not always been regarded as simple natural landscapes. According to oral traditions, they are the result of ancient metamorphoses, often linked to the hardness of the human heart. Several tales recount that long ago, these barren lands were once fertile fields, thriving villages, or even beautiful forests. But the pride, greed, or inhospitality of their inhabitants are said to have drawn a divine punishment or a supernatural one, turning abundance into desolation.

The moors, with their desolate appearance and vast stretches of heather, have not always been seen as simple natural landscapes. According to oral traditions, they are the fruit of ancient metamorphoses, often linked to the hardness of the human heart. Several tales recount that long ago, these barren lands were once fertile fields, prosperous villages, or even beautiful forests. But the pride, greed, or inhospitality of their inhabitants is said to have drawn a divine punishment or a supernatural one, turning abundance into desolation.

The heaths, with their desolate appearance and their expanses of heather, have not always been seen as simple natural landscapes. According to oral traditions, they are the result of ancient metamorphoses, often linked to the hardness of the human heart. Several tales recount that long ago, these barren lands were once fertile fields, prosperous villages, or even beautiful forests. But the pride, greed, or inhospitality of their inhabitants is said to have drawn a divine punishment or a supernatural curse, transforming abundance into desolation.

From then on, the heath became barren and its lands produced nothing ever again.

Another legend tells the story of the Lanvaux moor, once fertile. On a rainy night, Saint Peter and Saint Paul, dressed as poor travelers, knocked on the door of the richest house in the region, that of Mr. Richard. Not only did he refuse them shelter, but he threatened to unleash his dog on them. The saints finally found refuge with a humble man, Goodman Misery. As a reward, they granted him a strange power: whoever climbed his apple tree could not come down without his permission.

Even Death was trapped in the tree. Misery agreed to release her only after she promised to spare him until the Last Judgment. Furious, Death then struck the region, hitting men, houses, and trees. Since then, the moor has remained arid and desolate (according to Alfred Fouquet, Legends of Morbihan).

2. The Grass of Straying

Walking through the moors of Brittany or the Cotentin is stepping into a world that is both fascinating and unsettling. These seas of heather and gorse, stretching as far as the eye can see, have a strange reputation: they are said to harbor magical plants capable of making travelers lose their way. They are called the herbs of forgetting or herbs of straying.

In Brittany, belief in these mysterious herbs is deeply rooted. In the Morbihan, on the moor of Brandivy, grows the famous golden herb, or lezeuen eur. Anyone who steps on it after sunset is doomed to wander in an invisible circle until dawn. Even in broad daylight, its power to disorient is feared.

Not far from Saint-Mayeux, in the Côtes-d’Armor, another invisible plant is feared: the royal herb. Although no one has ever seen it, it is said to make any traveler lose their way, even on horseback. If a horse’s hoof steps on it, both the animal and its rider wander endlessly across the moor.

Belief in these plants extends beyond the borders of Brittany. In Berry, there is talk of the herb of engaire, which is said to grow in the vast desolate plain of Chaumoi de Montlevicq. As for the peasants of the Cotentin, they fear the male herb. Anyone who steps on it immediately sees the path vanish, wandering like a ship without a compass (Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, L’Ensorcelée, p. 29; Jean Fleury, Oral Literature of Lower Normandy, 1883):

« Quand on avait tourné le dos au Taureau rouge et dépassé l’espèce de plateau où venait expirer le chemin et où commençait la lande de Lessay, on trouvait devant soi plusieurs sentiers parallèles qui zébraient la lande, et se séparaient les uns des autres à mesure qu’on avançait en plaine, car ils aboutissaient tous, dans des directions différentes, à des points extrêmement éloignés. Visibles d’abord sur le sol et sur la limite du landage, ils s’effaçaient à mesure qu’on plongeait dans l’étendue, et on n’avait pas beaucoup marché qu’on n’en voyait plus aucune trace, même le jour. Tout était lande. Le sentier avait disparu. C’était là pour le voyageur un danger toujours subsistant. Quelques pas le rejetaient hors de sa voie, sans qu’il pût s’en apercevoir, dans ces espaces où dériver involontairement de la ligne qu’on suit est presque fatal, et il allait alors comme un vaisseau sans boussole, après mille tours et retours sur lui-même, aborder de l’autre côté de la lande, à un point fort distant du but de sa destination. Cet accident, fort commun en plaine, quand on n’a rien sous les yeux, dans le vide, ni arbre, ni buisson, ni butte, pour s’orienter et se diriger, les paysans du Cotentin l’expriment par un mot superstitieux et pittoresque. Ils disent du voyageur ainsi dévoyé, qu’il a marché sur male herbe, et par là ils entendent quelque charme méchant et caché, dont l’idée les contente par le vague même de son mystère.«

“When one had turned one’s back on the Red Bull and passed the sort of plateau where the road came to an end and the moor of Lessay began, several parallel paths appeared ahead, crisscrossing the moor and diverging from each other as one advanced across the plain, for they all led, in different directions, to very distant points. Initially visible on the ground and at the edge of the moor, they faded as one plunged into the expanse, and after walking only a short distance, no trace of them remained, even by day. Everything was moorland. The path had vanished. This was always a lingering danger for the traveler. A few steps could throw him off his route without his noticing, in these spaces where straying even slightly from the line one follows is almost fatal, and he would then move like a ship without a compass, after a thousand twists and turns, to reach the other side of the moor at a point far from his intended destination. This misfortune, very common on the plain when there is nothing to see, no tree, bush, or mound to guide one, is expressed by the peasants of the Cotentin with a superstitious and picturesque phrase. They say of a traveler so led astray that he has stepped on the male herb, and by this they mean some hidden and malicious charm, whose very vagueness satisfies them with its mystery.“Extrait de l’Ensorcelée, Jules Barbey d’Aurévilly

Fortunately, popular tradition offers a simple solution. In the Côtes-d’Armor, it is enough to touch a piece of wood or iron as soon as one suspects having stepped on the magical plant. This gesture breaks the enchantment and allows one to regain their way.

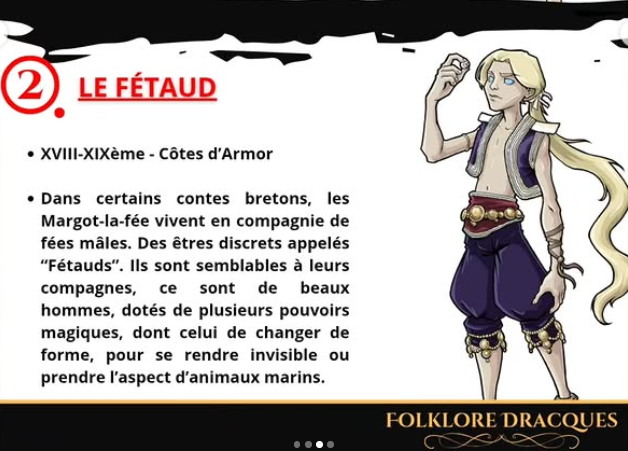

3. Spirits of moorlands

While forests sometimes shelter fairies and graceful creatures, the moors are considered the domain of malevolent spirits: goblins, revenants, giant ghosts, and unsettling apparitions. In the folklore of Brittany, Berry, or Provence, the moor is a place where the night unleashes mysterious forces.

In the Morbihan, the moors are inhabited by goblins who take refuge sometimes in megalithic ruins, sometimes in the thickets. They hide by day, but once night falls, they emerge to dance and mislead travelers. Crossing the moors of Pinieuc after sunset is a trial: the peasants say that thousands of shadows stir, mingling their clamors with the breeze. The only salvation is to reach a stone cross along the path before midnight and recite one’s prayers there. Without this, the willis lead the unwary into their infernal dances.

In Berry, the vast stony plain of Chaumoi de Montlevicq is renowned for its hauntings. At night, passersby may see illuminated chests, or even a blood-red cross that begins to follow them in the shadows. Legends also tell of the appearance of two long lines of kneeling ghosts, torches in hand, dressed in flour sacks. These are said to be the restless souls of dishonest millers from the Igneraie, condemned to endlessly throw burning flour in travelers’ faces. At the crossroads, a plot still bears the name Field of the Young Lady: there one might see a massive female figure that grows endlessly as one approaches, before vanishing into the air.

In Lower Normandy, the Faulaux is a type of spirit that takes the form of a lantern to mislead passersby and lead them into quagmires. It particularly hates whistling: a harness mender, caught in the moors of Lougé, happened to whistle. The Faulaux rushed to punish him. The worker threw himself to the ground and covered himself with his harness, but she struck with such force that the tip of an awl pierced his wickerwork. The more blood flowed, the more she believed she was striking the man, crying, “Little one, my poor little one!” When she realized the truth, she began to whimper and answered the mender’s question, “Who are you?” with the words: “I am Marie, your aunt.”

4. Ghostly Priests; White Ladies

The moors, already famed for harboring goblins and revenants, are also the stage for even more unsettling visions: headless ghostly priests, bloodied white ladies, and demonic creatures that torment travelers. In Breton, Norman, and Loire Valley (Ligérien) folklore, these nocturnal apparitions serve as a reminder that the moor is a passageway between the world of the living and that of wandering souls.

Around Paimpont, it was said that a ghostly priest appeared on the moor, ready to celebrate Mass, with lit candles by his side. He chased travelers, seeming to beg for something. But no matter how fast they fled, he always remained at their side… until Masses were said for the rest of his soul. After that, he vanished.

Not far from there, on the Longue-Raie moor at Saint-M’Hervon, an incredulous man heard a Mass bell ringing in the night. Suddenly appeared a headless priest, dressed in his sacerdotal vestments, surrounded by candles carried by invisible hands. A chilling vision that left a lasting mark on the village.

On the Vigneux moor (Loire-Inférieure), it is said that a headless woman crosses the heather without bending a single gorse bush. Upon reaching the crossroads of the Hutte au Broussay, she waits for a black goat with fiery eyes to appear, holding a severed head between its teeth. The woman tries to catch it, but the goat begins to leap in circles. Cries ring out, and soon owls and polecats swirl in this diabolical dance. A peasant, returning late from the fair, found himself trapped: against his will, he began to spin with the infernal troupe, until dawn finally drove the vision away.

In Elven, the White Lady wanders at night, dressed in a blood-stained gown. She reunites with the soul of her beloved, an officer who died defending her. Together, they exchange words of love that no one dares to disturb. In Lower Normandy, nearly every moor has its White Lady. The most famous is the Young Lady of Tonneville. In her lifetime, she declared:

« Si après ma mort j’avais un pied dans le ciel et l’autre dans l’enfer, je retirerais le premier pour avoir toute la lande à moi. »

“If after my death I had one foot in Heaven and the other in Hell, I would pull back the first so that I might have the whole moor to myself.”

Since then, she haunts these lands, leading travelers astray. One legend tells of a rider, captivated by her beauty, who invited her to ride pillion. When he tried to kiss her, she revealed monstrous teeth before vanishing, leaving him in the waters of the Percy pond.

A peculiar Breton legend speaks of a fantastic dwelling where three revenant women atone for their sins. A charcoal burner, lost on a moor, saw a light and entered a cabin. Three women welcomed him there:

They offered him food and money, but he refused. Immediately, everything vanished. Later, an old man revealed to him that these souls were performing penance: one worked on Sundays, the second kept the meat for herself and gave only the bones, and the third stole without scruple.

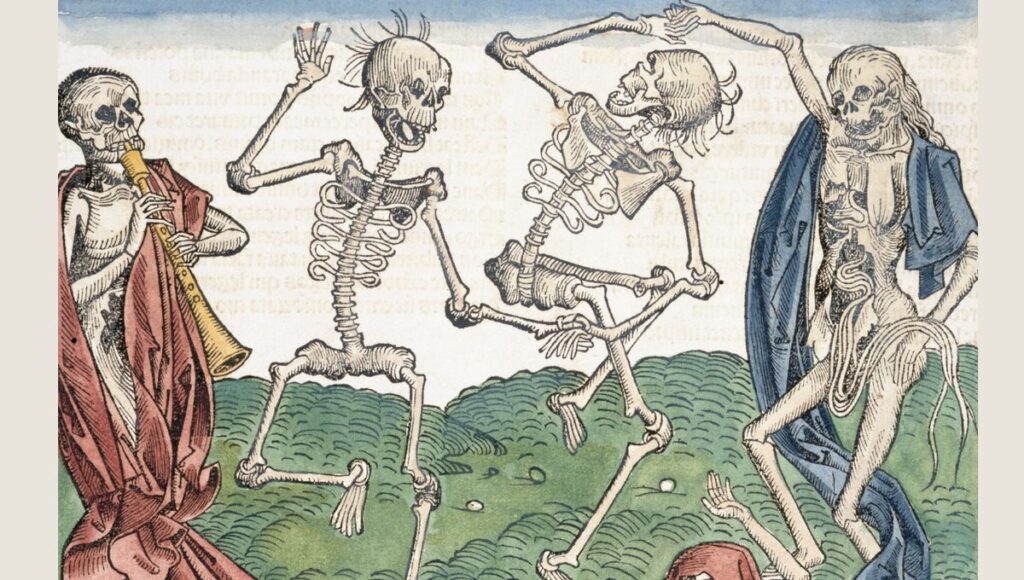

5. Macabre Dances

The moors, already famed for their ghostly priests, White Ladies, and goblins, are also the stage for macabre dances and spectacular gatherings of the dead.

In the Vaud region, the dead sometimes gather in crowds on deserted moors to perform the coquille, a winding dance that ensnares all who cross its path. The imprudent spectator, witness to this funeral round, often glimpses the specter of a living person who is soon to die, and sometimes even recognizes themselves as the central figure in this macabre chain.

A tale from Auvergne recounts that at the stroke of midnight, thousands of little restless souls appear on the moor to a young girl seeking refuge. They dance around her, singing a refrain. When the young girl adds two lines, the spirits offer her gifts. After several visits, she completes their chant, and thanks to her intervention, the souls announce that their penance is complete.

6. Ghosts in Animal Forms

The Breton moors are not only inhabited by White Ladies and goblins: some punished souls return in animal form to atone for their sins.

On the Minars moor in Clohars-Carnoët (Finistère), unjust notaries and prosecutors wander after death, transformed into old horses. Similarly, the Young Lady of Heauville roamed the moor that bears her name, sometimes taking the form of a mare from a nearby farm. Approaching a peasant who thought he recognized his animal, she would gallop to make him chase her, turning an everyday scene into a moment of supernatural fright.

In Lower Brittany, certaines âmes pénitentiellement errantes prennent la forme de souris blanches ou de moucherons, et se posent sur les arbres rabougris et les ajoncs nains des landes. En Upper Brittany, d’autres se manifestent sous l’apparence de papillons, errant autour des ajoncs lorsqu’elles n’ont pas trouvé de repos ailleurs. Les contes bretons mentionnent souvent la lande des Morts, où les défunts, sous forme ailée, circulent pendant des siècles, chacun autour de sa tige d’ajonc ou d’aubépine.

7. Lycanthropes

The moors are not only the domain of goblins and revenants: they also host beings connected to lycanthropy and temporary supernatural metamorphoses. These creatures are striking for their ability to unsettle travelers and transform ordinary scenes into truly fantastical experiences.

A legend from Norman folklore, the Varou is the local name for the Werewolf, cursed by the Church for having committed a crime and escaped justice, or for having been a witness to a crime and keeping silent.

While alive, he is condemned to the « Varouage », a nocturnal run through the countryside lasting seven years. According to Légendes de Normandie by Amélie Bosquet, the Varou, a damned soul, found no rest in death, and ripped open his grave to continue his run, ablaze with infernal flames.

In Vendée, werewolves would sometimes gather at the edges of the moors to feast and regain their strength after their metamorphoses. One night, a passing priest scared them away, and the cooking utensils they had abandoned were auctioned the following Sunday. In Avessac (Loire-Inférieure), the Melleresse moors were particularly notorious for these dangerous gatherings.

8. Devil, Witches, and Sabbaths

The moors and uncultivated areas of France were long perceived as dangerous and mysterious places, favorable to supernatural forces. Their isolation and the aura of fear surrounding them made them prime grounds for the Devil and his accomplices. In the Lower Pyrenees, Morbihan, Loire-Inférieure, and other regions, these deserted places were reputed to host male and female witches during their nocturnal gatherings, particularly at the height of witchcraft’s flourishing.

The demonologist Jean Bodin (De la démonomanie des sorciers) recounts that an inhabitant of Loches in Touraine threatened to kill his wife when she left the house at night. She confessed that she was going to a sabbat and offered to take him along. According to the account, they both anointed themselves, and the Devil transported them through space, from Loches to the moors of Bordeaux.

These gatherings, often called sabbaths, took place in various regions. The Grande Lande was reputed to host all the witches of Gascogne and its surroundings. In the Basque country, the site of the sabbath was known as Akhelarre, the “moor of the goat.” Near La Hague, witches, sometimes transformed into animals, would gather there, producing strange noises reminiscent of quarrelsome beasts. In the Gironde region, the Arlac moor was also famous for its nocturnal meetings. Participants would gather certain herbs, reputed to inspire love or heal ailments, which could be found only there.

In Armagnac, the moors of Urgosse, the plain of Midour, and that of the Catalan were also gathering places for witches. In Auvergne, the fatsillières danced in circles amid the heather and gorse, but any participant who stepped out of the magic circle was struck with paralysis. The Basques told that the Mairiac and the Lamigna met weekly on the Mendi moor, while in Périgord, devilish invocations mainly took place on the Lomagne moors, where a fallow esplanade was called Lou Soou de las fadas or de las fajilieras.

9. Animal Hauntings

The desolate moors of France are not only the domain of spirits and revenants: they are also haunted by fantastic animals that carry omens. On the Kerprigent moors in Saint-Jean-du-Doigt (Finistère), wanders a white doe, eerie and elusive. She follows passersby she encounters, never harming them, but her presence always foretells great misfortune. If she crosses paths with a young girl and blocks her way, the girl will marry quickly but die within the year. If she accompanies the girl, she will never marry. For a married woman, she portends the death of her husband, and for a widow, a period of mourning or financial loss. For young men, she predicts marriage or family misfortune depending on their age. This animal ghost is so feared that almost all who have seen it are said to have died. The black hound of Menez, in the Breton mountains, was also considered a harbinger of misfortune.

D’autres récits font état de batailles animales annonciatrices de grands événements. En Upper Brittany, on racontait avant la Révolution que des batailles de chats and rats se déroulaient sur les landes du Mené and Meslin, laissant certains animaux blessés. Un canton des landes de la Dordogne porte d’ailleurs le nom de Cimetière des chats, peut-être en référence à une telle légende. Une autre tradition bretonne rapporte qu’avant d’entamer une bataille, l’armée des rats et celle des chats furent détournées par leur capitaine, qui leur suggéra plutôt de brûler un vieux moulin voisin.

To protect travelers and ward off these hauntings, locals erected granite crosses on the highest points of the moors. Around the cross of the Brun moor in Plémy, for instance, the possessed could not approach without being freed there. The menhir of the Croix-Longue moor, near Guérande, was transformed into a cross to drive away witches. Similarly, on the Tiron moor, near Bains (Ille-et-Vilaine), a cross was erected at the center of the circle formed by witches during their nocturnal dance. These sacred markers served both as protection and as a guide for those venturing into these feared territories.

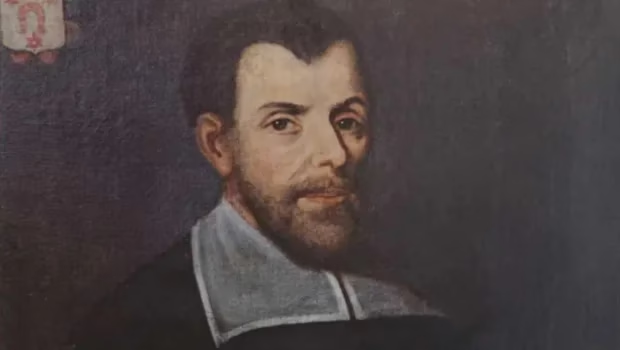

10. Bandits

Pierre Le Gouvello, Lord of Kériolet.

Just like the Corsican maquis, some French moors served as refuges for outlaws and bandits. These isolated and hard-to-reach areas offered an ideal shelter for those fleeing justice. While popular memory has preserved few detailed accounts of their exploits, one legend endures in the vast Lanvaux moor in Morbihan, famous in the early 17th century for harboring notorious thieves. According to this still-lively tradition, Pierre de Kériolet, famous for his misdeeds before turning to penance and being sanctified, mingled with the brigands alongside his friend Bonimichel.

Pierre de Kériolet, born in 1602 into a noble Breton family, initially led a violent, dissolute, and scandalous life. An inveterate gambler, indebted, seducer, and at times thief, he distinguished himself by immoral and proud behavior, attributing his “luck” to diabolical protection. His wanderings took him across Europe to Istanbul, in a quest for unbridled fortune and pleasure. The turning point in his life came during the famous possessions of Loudun: during an exorcism, his sins were publicly revealed, and he became aware of the extent of his sin. This spiritual shock led him to understand that his survival and “successes” had actually depended on the protection of the Virgin Mary. From that moment, he converted profoundly, adopting a life of penance, charity, and prayer. He donated his castle to establish a hospice and was ordained priest in 1637 at Vannes. Until his death in 1660, he led an austere and pious life, recognized for his sanctity. (see the video here, or the article).

11. Treasures

Leave a Reply