Hauntings of the house: mischievous elves and devils

Some beliefs present the night as the domain of wandering souls or of the Devil, prowling around households to enter at the slightest negligence. It is said that ghosts could return in the form of will-o’-the-wisps if no water was offered for purification, while the Devil watched mirrors and tripods to sneak into homes. But the night was not only threatening: it could also welcome benevolent beings, like Aunt Arie in Franche-Comté or fairies descending through the chimney to reward well-behaved children.

Legends place great importance on the mysterious signs heard in the nighttime silence: barking, birdsong, or unexplained noises were all omens announcing misfortunes or deaths. To protect themselves, families relied on precise rituals, ranging from spreading salt in front of the stables to placing knives under pillows, as well as offering seeds to elves to keep them occupied. These practices, inherited from a blend of Christian and pagan traditions, reflect an intimate relationship between humans, their homes, and invisible forces.

1. Forbidden acts: sweeping or leaving the fire on a tripod

At the end of the 18th century, around Lesneven (Finistère), this prohibition was strictly observed. It was called Scuba an anaoun, literally “the sweeping of the dead.” According to belief, this act drove happiness away from the home and disturbed the souls of the departed. It was said that the movement of a broom would harm and chase away the spirits wandering in the household once night had fallen. As a precaution, the tool was carefully put away at twilight.

This idea was not unique to Brittany: in other regions, nighttime sweeping remained forbidden for similar reasons. Everywhere, the night was considered the time of the dead, and every action inside the home could, it was believed, attract or repel their presence.

In the Breton-speaking part of Côtes-d’Armor, it is still believed that the souls of the dead return to visit their former home at nightfall. Sweeping at this time could chase them away with the dust. And if the wind brought back</strong} this dust, one must not throw it out a second time, under penalty of being disturbed all night by the deceased.

According to François-Marie-Guillaume Habasquet (Notions historiques sur les Côtes-du-Nord), on the eve of All Saints’ Day, this prohibition aimed to avoid driving away the souls in purgatory. It was also said that sweeping in the evening would scare away the Blessed Virgin, who came to see in which houses she could let in her favorite souls.

In some regions, the danger of nighttime sweeping was not aimed at spirits, but at the living. In Corsica, it foretold the death of a family member. In Loir-et-Cher, the head of the household would surely die if one swept before sunrise or after sunset—a belief particularly strong during Palm Sunday.

In several areas of the Armorican Peninsula, the hearth held a sacred role at night.

In Upper Brittany, extinguishing the hearth meant driving away the Blessed Virgin, who customarily warmed herself at fires that were still burning. The fire used to cook the porridge for a newborn was also kept going all night so she could prepare the porridge for the Baby Jesus. If a child fell ill in a house where this custom was not observed, it was seen as a punishment.

In Ille-et-Vilaine, leaving a tripod on the extinguished hearth caused the souls in purgatory to suffer. In Lower Brittany, it was feared that these souls might accidentally sit on an iron still hot, like the ghost of Gouarec who burned himself on a tripod heated by a malicious maid.

In northern Finistère, a pebble or a flat stone was once placed in a corner of the hearth, intended for the Bouffon Noz. But when a maid heated it red-hot, the elf burned itself and never returned.

2. Recommended actions: do not extinguish the fire and leave water

In Anjou, an old recommendation advises leaving a bucket full of water in the kitchen every evening. The reason? If a person in the household were to die during the night, their soul could wash there before departing. According to belief, the housewife who forgot this precaution risked seeing the sinful soul, unable to purify itself, return in the form of a will-o’-the-wisp.

Paul Sébillot notes that he did not find this custom in other French provinces. Yet, it persists in the Vallaise, a French-speaking region of Italy, where it is still advised today to never go to bed without leaving a bit of clean water for the needs of the souls.

3. Ways to drive away spirits

It was rare to try to drive the ghosts out of the house. Yet, in the Tréguier region, a traditional method was used to chase away spirits… but also elves. Before going to bed, small piles of sand were placed on the table. If the ghosts found them satisfactory, they were never seen again. This superstition, reported to Paul Sébillot in 1884 by G. Le Calvez, now deceased observer, illustrates a pragmatic approach: occupy the spirits in order to get rid of them more effectively.

More frequently, people sought to honor the deceased, especially on All Saints’ Day.

In Breton-speaking regions, the hearth fire was kept burning all night with a special log called Kef ann Anaon, “the log of the deceased.”

In some villages of the High Vosges, it was also believed that the dead came to warm themselves. During All Saints’ Week, fire was deliberately left in the hearth, and sometimes the beds were uncovered while the windows were opened… so that the departed could, for a single night, return to their former bed.

4. Considerations for the dead

Acts of respect toward the deceased are not solely rooted in affectionate remembrance of loved ones. They are primarily grounded in fear of the resentment of the dead.

Popular legends often describe the deceased as jealous of the living, quick to take revenge if treated disrespectfully. Thus, ignoring certain customs could attract their resentment or curses.

From the moment they were completed, houses were subject to protective ceremonies, whether Catholic (holy water, Candlemas candles, blessed branches from Palm Sunday) or pagan (apotropaic objects, figurines, images).

Yet, even thus fortified, they were not completely safe from incursions by the Devil or evil spirits, especially at nightfall. Tradition holds that they watch for the slightest negligence to enter inside.

In the 15th century, certain clumsy acts were believed to open the door to dark forces:

« Qui laisse de nuit une selle ou un trepié les piez dessus, autant et aussi longuement est l’ennemi à cheval dessus la maison… autant de gannes dyables sont assis dessus chascun pied. »

“Whoever leaves a saddle or a tripod at night with the feet on it, the enemy is equally and as long on horseback over the house… as many devilish creatures are sitting on each foot.”

In Upper Brittany, it is still said today that if a tripod rests with its legs in the air, the Devil is already in the house.

Another mistake was to leave a small saddle, with all four feet in the air, overnight:

« Autant est l’ennemi à cheval sur la maison… qui s’en va couchier sans remuer le siège sur quoy on s’est deschaussié, il est en dangier d’estre ceste nuit chevauchié de la quauquemare. »

“As much as the enemy is on horseback over the house… whoever goes to bed without moving the seat on which they removed their shoes is in danger of being ridden tonight by the quauquemare.”

5. The Devil in the houses

At night, in popular imagination, the night is not only the realm of ghosts and wandering souls. It is also the Devil’s hunting ground, ready to appear at the slightest imprudence. In Saint-Brieuc, a persistent belief warns women:

"If a woman looks at herself in the mirror after sunset, she sees the Devil behind her, over her shoulder.”

This superstition goes back a long way. In the Evangiles des Quenouilles, it was already written:

« Qui se mire en un mirouer, de nuit, il y veoit le mauvais et si n’en embelira jà pourtant, ains en deviendra plus lait. »

“Whoever looks at themselves in a mirror at night sees the evil, and if they do not yet adorn themselves, they will become even more pale.”

In short: looking at oneself at night brings neither beauty… nor peace of mind.

Several accounts report that, in times still close to our own, the Devil would appear in farms and inns where people danced after midnight. In the Pyrenees and Gascony, it is said that he can also come to those who speak too much of him once the sun has set.

Legends agree: the Devil never sleeps. In Lower Brittany, in the French part of the Côtes-d’Armor, as well as in Picardy, it is said that the night counts for him as much as a day. It is not uncommon for him to come to demand the fulfillment of a pact much earlier than expected, explaining to his victim:

“The day for us runs from six in the morning to six in the evening; and from six in the evening to six in the morning, there is still a day.”

Many victims were trapped, forgetting to specify that their years would be calculated based on twenty-four-hour days, and not on doubled cycles.

6. Benevolent spirits

While the night is sometimes associated with wandering souls or the Devil, some legends tell that it also harbors much more gracious nocturnal visitors. These creatures, true familiar spirits, show benevolence toward the households they favor.

In oral traditions, servants and sprites often put everything in order in the homes where they feel at home. Grateful, the inhabitants do not try to drive them away. On the contrary, they offer them small gifts in thanks for their good deeds.

In eastern France, in the region of Montbéliard, a legendary figure reappears regularly at Christmas time: Aunt Arie, the reincarnation of the benevolent countess Henriette de Montbéliard. The Francs-Comtois describe her as a charming fairy, riding the donkey Marion, a substitute for Santa Claus and Saint Nicholas, with a loving heart and a generous hand. She descended from the empyrean only at certain times of the year to visit:

She gave gifts to obedient and studious children, detested laziness, but showed a natural indulgence. Thus, if she caught a young girl with a bit of flax still hanging on her distaff at Carnival time, she would simply tangle it as a warning.

In Lower Brittany, an old belief tells that a very old fairy would descend the chimney on the eve of Saint Andrew. Her purpose: to see if, as midnight approached, the housewife was still spinning. If so, she did not fail to scold her.

In several tales, fairies also use this path to care for children or help afflicted people. But in the tradition of Essé (Ille-et-Vilaine), the chimney was sometimes used for more sinister purposes: it was through it that fairies descended to steal children.

7. Mischievous or malevolent elves

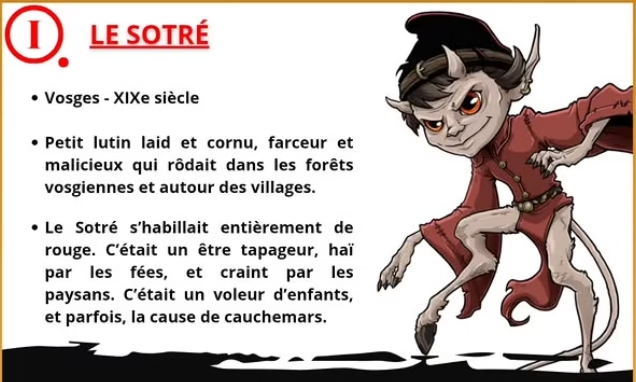

Night is also the time when certain mischievous spirits, often small in stature, come to disturb the sleep and peace of humans and animals. Among these nocturnal visitors, some enter houses solely to carry out their malevolence or pranks:

Faced with these nuisances, peasants use various means to drive away these malevolent spirits: chasser ces esprits malveillants :

These practices show how the night is considered a sensitive time when the visible and invisible worlds coexist, requiring vigilance and respect to protect the household and its inhabitants.

8. How to drive them away?

The most common way to repel elves is to place peas, millet, or ashes in a balancing container. The elf, arriving unexpectedly, bumps into it and overturns it. Forced to pick up each of these countless grains one by one, it quickly tires of the task and never returns.

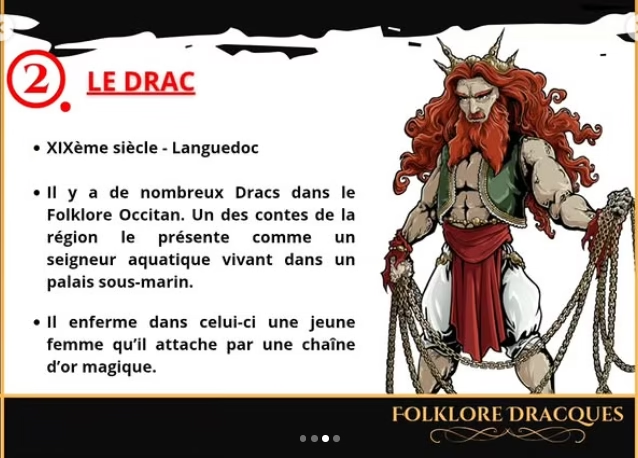

In Auvergne, flax seeds were simply placed in a corner. The drac, another mischievous spirit, preferred to leave rather than count them. In the same region, ashes were spread along the path of the Betsoutsou, who vainly tried to count them.

Sometimes, more radical methods were employed. The Faudeur of Upper Brittany stops oppressing anyone who threatens it with a knife. In the Beauce, people protected themselves from the Sotré-cauchemar or the lutin fouleur by opening a knife or crossing their arms.

In XVe siècle, on utilisait aussi la méthode de « vestant sa chemise ce devant derrière » pour se préserver du luiton. Une autre vieille pratique disait :

« Qui doute la cauquemare qu’elle ne viengue de nuit à son lit, il convient mettre une sellette de bois de chesne devant un bon feu, et se elle venue se siet dessus, jamais de là ne se porra lever qu’il ne soit cler jour. »

In Wallonia, pour repousser ces esprits, il fallait déposer ses souliers avec les talons dirigés vers le lit, ou bien un soulier dans un sens, l’autre dans le sens inverse. La croyance voulait que la mark ne puisse monter sur le lit qu’après avoir chaussé les souliers, et que ce placement inhabituel les en empêchait.

The métal, et notamment la lame du couteau, était autrefois considéré comme aussi efficace que son tranchant pour repousser les esprits. En Lorraine, le sel était répandu à la porte des étables, le premier mai, avant le lever du soleil, pour empêcher le Sotré de venir traire les vaches.

As for doors, they must remain closed at night, not to keep out thieves, but to prevent the entry of malevolent spirits. In Gironde, opening a door at midnight, especially after a death in the family, exposed one to misfortune. On the island of Ouessant, it was avoided to pass a burning ember under a door, as the returning elf Lannig an aod would first grab the arm, then the whole body, causing the disappearance of the careless person.

In the Aude, to protect the house from visits by the Masque (or masco), a spirit that takes human form during the day, a vase filled with water is placed near the keyhole or cat flap, with an old pair of pants suspended above it. The pants usually drown in the water. If it nevertheless enters the house, it is warded off with these words:

« Pét surfelho, passo la chiminiero »

« Recule, remonte par la cheminée »

“Step aside, go back up the chimney”

Leave a Reply