Anthropomorphic rocks: giant heads, female silhouettes, and divine punishments

1. Ce qu’elles sont

We encounter many such examples in Antiquity. Thus, Lot’s wife was said to have been turned into a statue as punishment for her curiosity. Niobe, for her part, underwent a comparable metamorphosis following misfortunes that became legendary, and that were in fact told in several quite different versions. In the time of Pausanias, a rock known as Niobe was pointed out on Mount Sipylus, in Attica. The Greek traveler once climbed up specifically to observe it. Here is what he reports:

“What is true is that, when you look at it up close, it has no human features at all; but if you see it from a distance, it does indeed seem to you like a woman in tears, overwhelmed with grief.”

Niobe continues: “Personal experience of direct observation confirms this reality. I have had occasion to verify it on several occasions while painting from life. Thus, near Paimpol, I began around two o’clock in the afternoon a study of a strangely shaped rock, which at that time showed nothing anthropomorphic. Yet, when the sun, lighting it from behind, was about to disappear, I noticed that its summit bore a striking resemblance to a woman leaning forward, bending the knee in an attitude of prayer. I returned to the spot the following morning and was able to convince myself that the stone, this time lit from the front, did not resemble a female statue in any way.”

In regions where tradition places destroyed or submerged cities as the result of catastrophes comparable to the punishment of Sodom and Gomorrah, local inhabitants sometimes point to anthropomorphic rocks as the remains of figures petrified like Lot’s wife, and for the same transgression.

At La Bastide Villefranche, two stones of unequal size are pointed out, called Mother and Daughter. On each of them are engraved dice and scissors, distinctive signs that reinforce their identification.

According to local tradition, these stones are said to be a mother and her daughter turned to stone as punishment for their curiosity, at the moment when a fire destroyed, not far from there, a settlement called Belle Mareille. Like Lot’s wife, they supposedly wanted to see what should not have been seen, and were frozen for eternity.

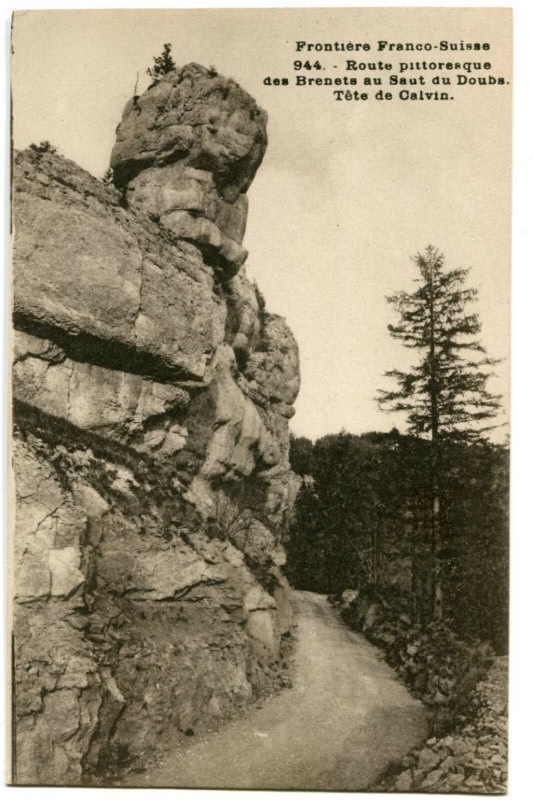

2. Heads of Giants or Heroes

Several examples testify to this tendency to humanize the rock:

This anthropomorphic rock is said not to be a mere trick of nature. A young noblewoman named Marie Mâtre used to meet her lover at night in the middle of Lake Nantua, each arriving by boat from opposite shores. One stormy night, the young girl’s boat capsized and she drowned. In memory of his beloved, the young man is said to have sculpted this rock and given it a human shape, naming it Maria Mâtre.

In the region, where this rock is very popular, children are still lulled to sleep with this refrain, sung to a mournful tune:

Marià Mâtre

Who ate the tattar

And gave none to her husband,

Oh! the sly one!

The original article is accompanied by a photograph of the rock (Louis Cognat, in La Tradition, 1902, pp. 258-269).

It is rarer for anthropomorphic blocks to bear the name of a saint. However, an isolated rock located on the eastern part of a mountain called Tracros, four leagues from Clermont-Ferrand, which from a distance takes the shape of a statue, is called Saint Foutin by the locals. This figure is known to be frequently associated with procreation. Indeed, the shape of the rock is characterized in a way that leaves no doubt about the reason for its name: when viewed from the plain to the north or northwest of Tracros, one can clearly distinguish boldly pronounced phallic forms.

Even more often, these rocks evoke the idea of monks or female figures. Their upper part, frequently shaped by erosion into a conical form, outlines a hood or a headdress against the sky, while the base can, with little imagination, be taken for a dress.

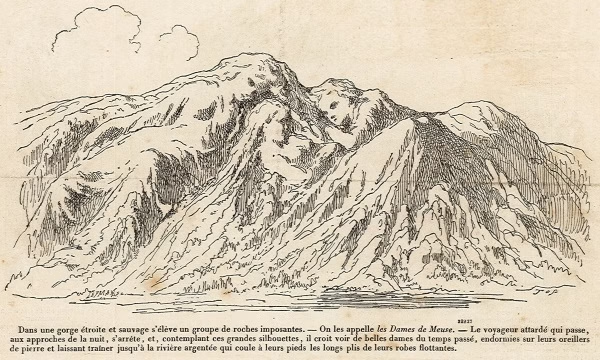

3. Rocks with Feminine Shapes

In the vicinity of Pleigne, the Maï’s Daughter, a rock about 33 meters high, features a woman’s head crowned with a Scots pine. The upper part of the torso is visible, while the rest of the body is modestly hidden in the foliage. Viewed from the front or in profile, up close or from a distance, the resemblance to a woman is striking.

At Condes, a rocky spire, which from a distance resembles a statue, is called the Lady of the Sleeve.

Near the former priory of Vaucluse, a rock resembling a seated woman is known as the Woman of Bâ. It has been personified to the point that a popular saying is attributed to it:

“The Woman of Bâ puts on her white clothes at sunset, it will be fine tomorrow”

“The Woman of Bâ puts on her black clothes, it will rain”

Some natural formations, arranged three by three, have inspired the idea of gatherings of women, often linked to dramatic stories.

In Corsica, where metamorphoses of people or animals are frequent, several stories arise from a curse. Notably, there is the one that turned a wedding into the summit of Sposata Mountain. Another legend tells of a lazy girl, busy picking flowers instead of bringing in the laundry, who was cursed by her mother:

“Even a bucket for you no more, and your laundry too! May you dry forever, you and your clothes!”

Rocks whose appearance has led them to be named monks are just as numerous.

Finally, a legend tells that a devil, having splashed the head of a penitent hermit, was turned into a rock. He took the shape of a hooded monk, head bowed before the cave, while his accomplices remain visible nearby, along the banks of the stream.

4. Petrified Impious Figure

In the high, heather-covered plain separating the village of Ortho from the valley of the Ourthe, a shepherd was grazing his sheep. A pilgrim, dying of thirst, implored him for a cup of water in the name of Saint Thibault, highly venerated in the region. The shepherd refused. The pilgrim moved about twenty steps away and sat down. The shepherd threatened him with his staff, then, finding him too slow to leave, threw a stone at him. But the stone, repelled by a divine hand, struck the wretched man, who was petrified on the spot along with his flock. These rocks are known as the Stones of Mousny. Tradition adds that the thirsty pilgrim was none other than Jesus Christ himself.

On the road to Mount Saint-Vallier, one can see the ancient sheep, Los oueillos antiquos. This is an arrangement of white stones lined up like a flock, the shepherd at the front, the dogs at a distance. God, passing by, asked the shepherd:

“Where are you going?”

— To lead my flock up this mountain, whether it wants to or not,” replied the shepherd.

Immediately, the shepherd and his beasts were turned to stone.

Further along, on Mount Saint-Savin, the Turning Stone is a jagged rock jutting from the ground on the mountainside. Long ago, a giant was chasing a young girl there. At the moment he was about to reach her, she invoked divine intervention. The giant was then frozen upright, turned into living rock from head to toe. Since then, it is said, he is permitted to move only once every hundred years, on the anniversary of his crime.

A legend from Guernsey explains the anthropomorphic appearance once possessed by a rock, now destroyed, known as la Roque Màngi. It stood in the sand dunes of the northeast coast. The formation consisted of a rocky mass eight to ten feet high, topped by a large stone resting on the narrowest part of the other. Seen from a short distance, it resembled a petrified giant.

The peasants told that the devil, having quarreled with his wife, had tied her by the hair to the upright stone. In her desperate efforts to free herself, turning her head from side to side, she is said to have worn down the solid granite, reducing the rock to the narrow neck that supported the “head.”

5. Characters from Tales Transformed

Unlike local legends, where large stones often occupy a central place, proper folk tales more rarely mention the transformation of characters into anthropomorphic blocks. When this motif appears, it follows a very specific logic: the hero’s fault, almost always linked to forgetting or transgressing a fundamental taboo.

In these tales, the metamorphosis generally occurs during a difficult task, undertaken by a hero who has been given a single instruction, the only one capable of saving him from the fatal fate of his predecessors. To forget this instruction, to give in to fear or curiosity, is to expose oneself to irreversible petrification.

A Provençal tale perfectly illustrates this pattern. It concerns the quest to seize three wonders:

Those who failed to ignore the shouts and insults encountered along the way are turned into rocks at the very moment they look away. The punishment is immediate, automatic, and allows no room for repentance.

Other adventurers, setting out to conquer similar wonders, suffer the same fate when they lose courage while climbing the mountain amid hail and snow. Human weakness in the face of the trial becomes here an irreparable fault.

In a variant of the story, anyone who, while climbing the tree atop which sits the Singing Apple, touches even one of the many fruits it bears, is immediately turned to stone. The gesture, though minimal, is enough to break the balance and freeze the body for eternity.

6. Animals Turned to Stone

On the shores of certain lakes covering submerged cities, or said to be visible beneath the waters, rocks depicting animals are pointed out as proof of divine punishment. Their presence reinforces the idea that the catastrophe struck not only humans, but also the animals that shared their fate.

Other animals were turned to stone alongside humans, notably in the stories of stone hunts. The dogs from these legendary hunts are still visible:

These animals, frozen in the midst of the chase, extend in the landscape the image of a hunt eternally halted.

On the Campotile Plateau, in Corsica, two roughly similar large rock blocks are called the Devil’s Oxen. According to tradition, Saint Martin petrified them while Satan, furious at being unable to fix the plowshare, threw his hammer into the air. A stone placed horizontally above the blocks represents their yoke.

Another version of the story specifies that the devil was plowing this plateau so that the herds could no longer graze there. Saint Martin, through prayer, first caused the plowshare to break. But Satan forged another, so strong that it split the rock without dulling. The saint recited twelve dozen rosaries without success; on the thirteenth, the oxen stopped abruptly and were turned to stone.

Above the village of Montgaillard, there is a cow-shaped rock. According to legend, it is the Cow of Arize, which had shown humans the source of Barèges. After completing this beneficial task, the animal was transformed into stone, as if to remain forever the silent guardian of the water it had revealed.

7. Rocks Resembling Constructions

Sometimes, people, struck by the striking resemblance of certain rock formations to human constructions, see in them the remains of ancient cities, ruined under marvelous or cursed circumstances. These mineral landscapes then become imaginary ruins, inhabited by fairies, ghosts, or the devil himself.

On the slopes of a hill near Villefranche-sur-Saône, scattered blocks are regarded as the remains of a cursed city, now home to fairies and ghosts. Each year, it is said, when the bells ring in the middle of Christmas night, a long procession emerges from the depths of the destroyed city and wanders among the ruins. Any living person daring enough to join this procession would be infallibly struck dead, a reminder that these places belong to the otherworld.

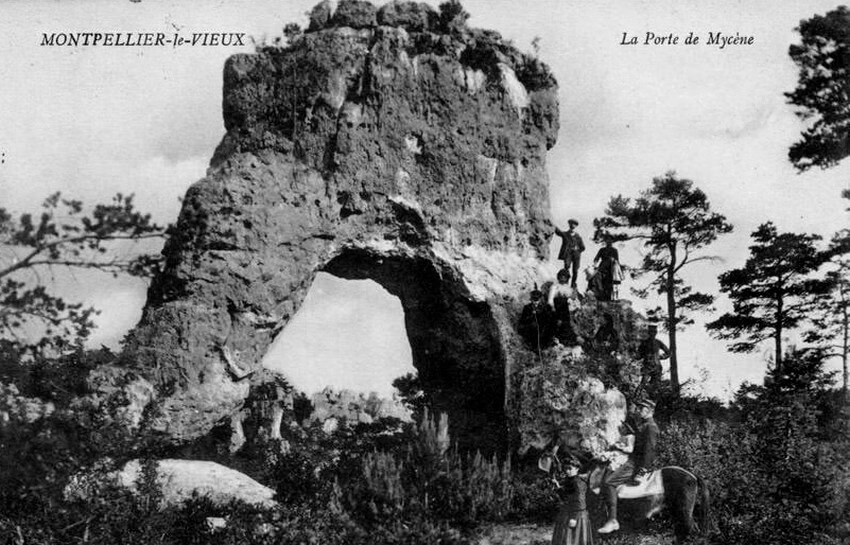

The shepherds of Aveyron feared approaching a natural formation not far from Millau, called the Devil’s City or Montpellier-le-Vieux. They imagined that it had been built by a race of giants and then destroyed by the devil.

Dans une autre région, une tradition locale affirme que les pierres gigantesques qui hérissent les collines de Poullaouen sont les débris du palais d’Arthur. Le roi y aurait enfoui ses trésors en quittant la Bretagne. Le diable et ses fils en seraient les gardiens : on les aurait vus rôder sous forme de follets, et tout téméraire cherchant ces richesses serait épouvanté par leurs cris.

In Creuse, un gros amas de rochers est appelé Châté de las Fadas, the château des fées.

In Bordes, dans l’Yonne, le plus imposant des blocs d’un ensemble rocheux porte le nom de Four du Diable. Autrefois, on menaçait les enfants de les y conduire, utilisant le paysage comme instrument de crainte et de discipline.

8. Objets pétrifiés