Stars and Constellations: the Stellar Chariot and the Mystical Stars

1. The Milky Way: an origin linked to Saint James

In the countryside of France and Wallonia, the Milky Way carries a name deeply rooted in Catholic tradition: the Way of Saint James. It is seen as the celestial path guiding pilgrims to Saint James of Compostela in Galicia.

Each region has adapted this name to its own language or dialect:

These names all recall the sacred pilgrimage to Compostela, once undertaken by thousands of believers.

In some legends, the Milky Way is seen as the last celestial river, a remnant of the seas of the firmament that supposedly receded. This reflects an ancient memory where the sky and the sea were intertwined.

In certain regions, it is given names that emphasize this passage to the afterlife:

In Antiquity, it was the road of souls leaving Earth for the afterlife. Later, in the Middle Ages, it took on a more pronounced Christian symbolism: that of the path of eternity, guiding souls toward their salvation.

In Wallonia, the Milky Way is sometimes called li Tchâssey romin-n – the Roman Road. A local legend tells that the devil tried to build this celestial path in a single night. But the crowing of the rooster, heralding the dawn, interrupted his work. This story reflects the association of the Milky Way with the ancient Roman roads, which the peasants of Hesbaye still saw winding through the fields.

The Chronicle of Turpin (pp. 427-428), a famous medieval legend, tells that Saint James appeared to Charlemagne while he was gazing at the Milky Way. The saint showed him the path of stars that would lead him to Spain, toward the discovery of his tomb.

In Provence, another tradition holds that it was Saint James himself who traced the Milky Way to guide Charlemagne during his war against the Saracens.

2. Origin of the Stars

For many, stars are not mere points of light. They play a fundamental role in the balance of the world and the destiny of human beings. They appear suspended in the firmament, much like the starry paintings that adorn the ceilings of certain churches.

In other traditions, stars are described as:

In the folklore of Upper Brittany, a children's riddle captures this poetic perception:

“I have lost my stitches; unfortunately, I can only find them when the sun has set. What are they?”

The answer, of course, is the stars.

3. The Big Dipper and Its Names

Since the Middle Ages, the Big Dipper has been seen as a chariot drawn by animals. In the Roman de Rou by Robert Wace, one of the oldest French texts, we already read: « Tot dreit devers Setentrion – Que nos char el ciel apelon. » (“Straight toward the North – Which we call the chariot in the sky.”)

Until the 17th century, this constellation was commonly called the Chariot of the Sky. Depending on the region, the names vary but retain this idea of a celestial vehicle:

The Walloons also call it Chaûr-Pôcè, a name that might refer to a version of the Tom Thumb tale, in which he becomes an ox driver.

Behind these names lie precise legends that tell how this chariot was lifted into the sky, who drives it, and why it is there. In some versions, it is King David who, after his death, was placed in the sky. Elsewhere, the driver is Saint Martin, Tom Thumb, or even a nameless man punished for his sins.

The Walloon and French tales echo ancient Germanic legends, such as that of the punished celestial chariot, or the figure of Philomelos in Greek mythology, the inventor of the celestial chariot.

In several traditions, the constellation is interpreted in detail:

In a dialogue, a shepherd explains to young Frédéric Mistral that the Big Dipper corresponds to the « Good Lord’s Chariot », and that the small stars around the chariot are the souls recently risen to Heaven (Frédéric Mistral, Armana Prouvençau, 1872, p. 40 Gallica).

In many regions, the celestial chariot is associated with an imperfection or imbalance: In Brittany, it is called ar C’harr gamm, the Lame Cart.

In the Messin region, the horses are poorly harnessed, and it is believed that the world will end when the coachman Alcor manages to bring them back into line.

In Vivarais and the High Vosges, people see in the Big Dipper a handle-less pot, in which a little man (the star Alcor) watches the cooking: when the water boils, it will be the end of the world.

Other legends, particularly in the southeast of France, speak of blasphemous men transformed into a constellation along with their animals and servants, as a divine punishment.

The most famous of these stories comes from the Basque Country: two thieves steal a pair of oxen from a ploughman. After sending his servant, his maid, and even his dog to chase them, the ploughman eventually sets off himself. None of them return. Mad with rage, the ploughman swears and blasphemes. Jinco (God) then condemns him, his retinue, and the thieves to walk eternally in the sky, forming the Big Dipper:

In Gascony, a variant replaces the oxen with a cow and a bull.

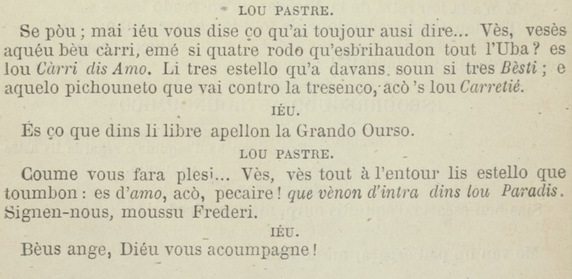

The Shepherd

– That’s right; but I’ll tell you what has always been said… See, see that beautiful chariot, with its four wheels shining up there? It is the Good Lord’s Chariot. The three stars in front are its oxen; and the little star next to the third one is the Coachman.

The Young

– That is what is called the Big Dipper in books.

The Shepherd

– As you see, boy… Look, look at all the little stars falling around: they are souls, those said to have just entered straight into Heaven. Let us make the sign of the cross, my dear Frédéric.

The Young

– Beautiful angel, may God be with you!

3. Particular stars

In Provence, the Pole Star, called Tremountano (or Tramontane), serves as an essential landmark for sailors. When they lose sight of it, they believe themselves lost. Located in the constellation of the Little Dipper, the star guides navigators who, when facing the north wind, say they are going « to the Bear » (à l’Orso).

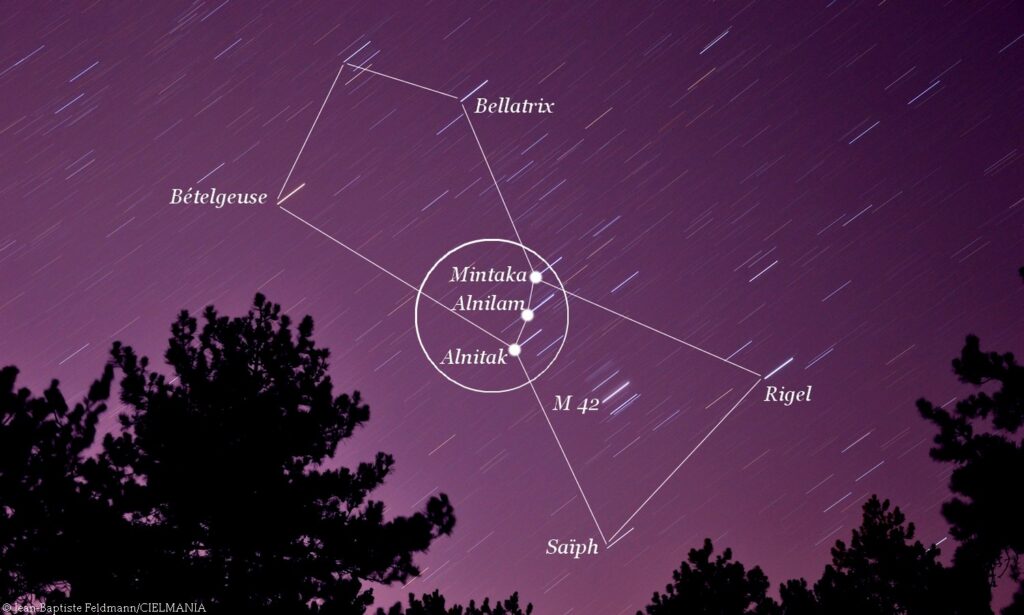

The three aligned stars of Orion’s Belt are the subject of many names:

Each region has thus projected its own images onto these three stars, often associated with agricultural tools or biblical figures.

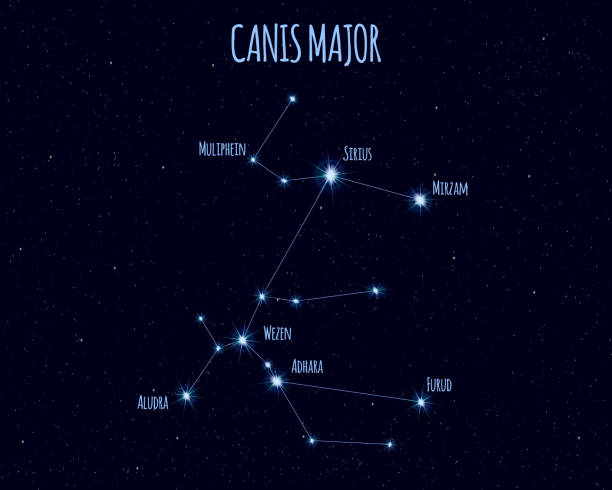

The Pleiades cluster (M45), recognizable by its shape as a small group of closely packed stars, is also prominent in beliefs:

Here, the stars become hens surrounded by chicks, protective images associated with motherhood and fertility.

The brightest star in the morning or evening sky, Venus, is almost everywhere referred to as the Shepherd’s Star. Other names further enrich this designation:

A legend tells that the Beautiful Maguelonne (Venus) pursues Pierre de Provence (Saturn), whom she marries every seven years.

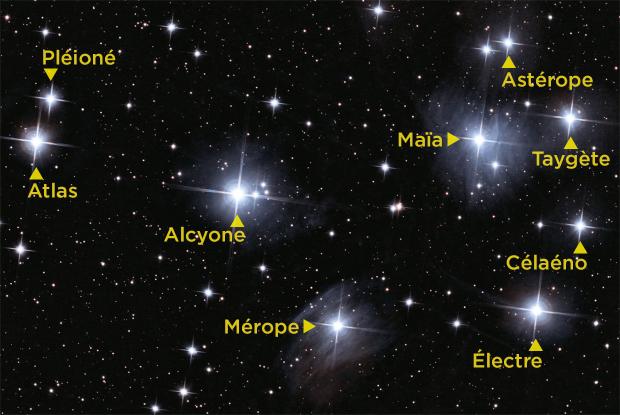

In Provence, the star Sirius is known as Jan de Milan. A legend tells that one night, Jean de Milan, the Three Wise Men (the stars of Orion’s Belt), and the Poussinière were invited to a celestial wedding. The Poussinière left early, the Wise Men overtook her, but Jean de Milan, being lazy, got up too late. Furious, he threw his stick, which formed the three stars of the Scythe Handle, known as the Stick of Jean de Milan.

The star Antares, nicknamed lou Panard (the Lame), was also supposed to attend the festivities but arrived too late, moving slowly across the sky.

Some stars are associated with Christian ideas: in Wallonia, the Shepherd’s Star precedes the two chariots (the Big and Little Dipper), and whoever follows it will symbolically reach the tomb of Christ in Jerusalem. In the Liège region (Laroche), only a person free of mortal sin can see the Swan Cross.

Several stories associate the stars with fantastic journeys or parallel worlds: in Gascony, a tale tells of the Master of the Night who locks his fiancée in the central star of the Three Bourdons. In the Perche, a fairy transports a man she wishes to reward to a star where one never dies.

According to the Tales of King Cambrinus, a young girl who falls into a well finds herself in a star, highlighting the connection between the deep earth and the high sky.

4. Birth and Fate Influenced

In certain regions of Upper Brittany, when a child is born at night, it is customary for family members and neighbors to step outside to observe the star above the main chimney. If this star is bright, it heralds a happy future for the newborn. But if it is pale or veiled, it is a bad omen.

This belief is confirmed by several traditional tales from the Côtes-du-Nord. In one of them, a poor man, witnessing a birth, advises delaying the child’s arrival by an hour: otherwise, according to a seer’s prophecy, the child would be born under a bad star that would condemn him to be hanged at the age of twenty. Thanks to a heavenly intervention, the tragic fate is ultimately avoided, and the child is saved from this dreadful prediction.

Another legend from Upper Brittany tells the story of a young girl born under a bad star. To ward off misfortune, she must exile herself for seven years away from her homeland and give birth to seven illegitimate children before she can return home.

5. Shooting Stars and Souls

In the traditions of several regions, when stars fall to the horizon, it is said that they drown in the sea. This belief is referenced in the verses of the poet Charles Leconte de Lisle in La Chute des étoiles: “Fall, O undone pearls / Pale stars, into the sea.”

In the southern Finistère, it is said that stars, upon crossing a mountain that blocks their path, then fall to the ground or into the ocean if they cannot find their way.

For centuries, shooting stars have been associated with human souls. A medieval belief, still alive in the 15th century, held that each person has their own star and that, when they die, the star falls from the sky. A prayer would then be recited so that the gates of Heaven would open to the soul of the deceased.

In many regions, the fall of a star is interpreted as the death of a loved one, often of a guilty or unfortunate person. For example:

In other stories, shooting stars are the souls of the deceased rising to the sky, sometimes released from Purgatory through the prayers of the living.

In Audierne, the souls walk all night toward Heaven. If they move quickly, it is because they have been freed by prayers. In the Norman Bocage, it is the soul of a child ascending to the sky.

In Auvergne, a legend tells that after a thief returned stolen goods to the Church, a shooting star appeared, signaling the liberation of the deceased’s soul. Everywhere, these celestial appearances are seen as calls to prayer to hasten the release of souls in distress.

Summer nights, particularly during the meteor showers known as the tears of Saint Lawrence, are considered the prime time when the departed make themselves known to remind the living of their presence.

Depending on the region, there are specific formulas to recite when one sees a shooting star:

6. Wishes and the Traces They Leave

The custom holds that anyone who makes a wish at the exact moment a shooting star passes will see that wish granted. It is even said that if one has time to make three wishes, all will come true.

In some regions, these wishes take on particular forms: in the Vosges, it is said that fortune will come to anyone who, as the star passes, utters the words: « Paris, Metz, Toul », referring to the three major cities of the East, in connection with a marvelous vision: that of a dragon carrying a diamond between its fangs.

In Gironde, if one thinks intensely about something and sees a shooting star while looking up, that thought will come true. In the Nièvre, seeing a shooting star prompts one to make the sign of the cross while asking God to overcome their chief flaw.

Some traditions claim that shooting stars can leave tangible marks of their passage on Earth: in Wallonia, it is said that they may deposit celestial droppings, kinds of gelatinous masses sometimes found in marshes. These remnants, locally called hit’ di steûl, are in fact frog skins vomited by predators, but older generations associate them with falling stars. According to the inhabitants of La Reid, the blue pierced stones scattered throughout the countryside are also said to be remnants fallen during star showers.

7. Omens Drawn from Shooting Stars

In Liège, a young girl wishing to discover the identity of her future husband must, every evening for seven days, count seven stars. If clouds prevent her from seeing the sky, she must patiently begin her cycle again. The first young man to offer her his hand will then become her husband. This practice is also found in Creuse and in Nivelles, where one must count not seven but nine stars for nine days.

🌟 🌟 🌟 🌟 🌟 🌟 🌟 🌟 🌟

In the Vendée Bocage, superstition holds that whoever manages to count seven stars on seven different evenings will see the truth in the dream of the seventh night.

🌟 🌟 🌟 🌟 🌟 🌟 🌟

The stars also guide the fate of those who know how to observe them:

In Poitou, a legend says that children who fast on Christmas Eve see, through the chimney flue, the beautiful star that reveals the nest.

The stars are also sources of omens, sometimes favorable, sometimes troubling:

Shooting stars hold a special place in popular imagination:

Some beliefs call for caution: in the Vosges and in Vendée, it is strictly forbidden to count the stars: whoever counts their lucky star dies instantly. In Marseille, pointing at the stars with one’s fingers exposes one to getting warts.

8. Remnants of the worship of stars and witchcraft

In the 15th century, a star nicknamed Poussinière was particularly revered because of its name, which evoked the protection of chicks. It was said that anyone who, at bedtime, greeted this star with respect would never lose a single chick, and that their broods would double in number. The traditional formula said:

"Whoever at bedtime greets the Poussinière star will not lose any of their chicks, and they will double in number."

Even in the 18th century, some stars still inspired respect. Around Plougasnou, in Brittany, a few devout men would drop to their knees as soon as they saw the Star of Venus, considered a sacred sign.

In Lower Brittany, a religious practice called the fast of the nine stars was observed on Christmas Eve. Whoever abstained from food from sunrise until nine stars became visible in the sky gained a strange power: at Midnight Mass, they could see Death touch with a finger the people destined to die within the year.

In popular beliefs, witches were capable of influencing astral revolutions through secret incantations. The stars, in this context, were not merely celestial bodies: they were sensitive entities that could be manipulated, for better or for worse.

In Gironde, upon seeing a shooting star, one could recite these protective words:

"Saint Catherine, I see you, do not fall!"

Leave a Reply