Is the Mountain carved by giants?

The mountains nourish the collective imagination. Mysterious massifs, peaks with strange shapes, or pierced rocks — they have given rise to countless tales passed down from generation to generation. Giant builders, an enraged devil, or petrified heroes: each landform seems to preserve a legend in which humans try to explain the inexplicable.

Partout dans les régions de France et d’Europe, ces récits folkloriques attribuent aux giants such as Gargantua, Roland, or Hok-Braz the creation of hills, breaches, or even entire mountain ranges. A toppled basket becomes a mountain, a pulled-out tooth takes the shape of a solitary peak, while a sword strike splits the rock to open a passage. Other stories evoke the devil, furious, hurling his tools at the Corsican peaks, or optical illusions in which the silhouette of Napoleon appears in the eternal snow of Mont Blanc.

1. Its folklore and its sources

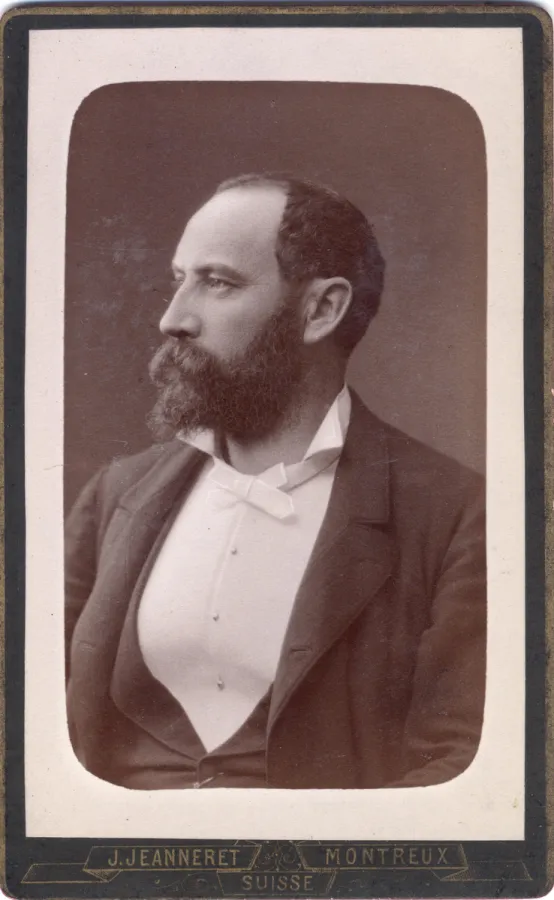

Mountain folklore in French-speaking countries has only rarely been the subject of a true scientific study. The stories we have come mostly from literary works, where the elegance of style has often taken precedence over ethnographic accuracy. The Legends of the Vaud Alps by Alfred Cérésole are a good example: the author gathers local traditions, sometimes taken from scattered publications, sometimes collected by himself. But in seeking to give his narrative a pleasant form, he did not always preserve the authenticity of the oral tradition. As a result, while the substance of the stories is credible, it is difficult to distinguish what belongs to the true popular heritage from what stems from literary embellishment.

Other works show the same limitations, making the study of these traditions particularly complex. Among all the surveys conducted by the Revue des Traditions populaires, the one on the folklore of the mountains has remained the least fruitful. In French-speaking Switzerland in particular, this theme is scarcely present, even in the Swiss Archives of Popular Traditions. However, the stories they contain can be considered reliable and serve as valuable sources.

2. Giants and mountains

If the people rarely explain the formation of the great massifs, they readily attribute the origin of certain peaks to giants. In Belgian Luxembourg, it is said that colossi living in the bowels of the earth fought with such violence that the earth’s crust was lifted. The mountains are nothing more than the scars of these titanic battles.

Other stories feature Gargantua. When he supposedly dug Lac Léman, he piled up the clods and rocks on the left bank. Seeing this mass grow, the inhabitants exclaimed: “Hey! It’s rising!” – a legendary origin of the name of Mont Salève. Further south, in Beaujolais, the stones that Gargantua is said to have pulled from the bed of the Saône formed Mont Brouilly.

Brittany also preserves powerful stories. The giant Hok-Braz is said to have built, almost playfully, the Monts d’Arrée range, from Saint-Cadou to Berrien. He even placed Mont Saint-Michel of Brasparts there. This episode was first published in 1874 in the Publicateur du Finistère, then taken up by Ernest Du Laurens de la Barre in his Nouveaux Fantômes bretons. Although heavily romanticized, this legend illustrates the poetic power of mountain myths: the landforms become the silent witnesses of the games and wrath of giants.

3. Gargantua

In many regions of France and Switzerland, natural landforms are attributed to the exploits – and clumsiness – of Gargantua. It is said that he planned to raise the Colombier de Gex to the height of Mont Blanc. To do so, he fetched materials from the Alps, carrying them in a huge basket. But one day, one of his straps broke: his load toppled, forming the hill of Mussy.

While digging the Val d’Illiez, Gargantua struck the rocks of Saint-Triphon with his foot while trying to drink from the Rhône. He lay down in the valley, shouting: “Hey! Up it goes!”. His overturned basket spilled the earth, forming the hill of Montet. According to the Genevans, this name comes from his exclamation. Furious, he kicked his basket and scattered the remaining earth, giving rise to other hills. The same adventure repeated near the Sarine, where the contents of his basket formed the small mountain of Château d’Œx.

Gargantua did not only shape the Alps and French-speaking Switzerland. In Beaujolais, the Dent de Jamant and Mont de Roimont are said to have originated from the same clumsiness. Further north, in Laonnais, he was carrying earth in his basket, but overloaded, he dropped part of it. This pile formed the hill on which the city of Laon stands today.

In a Valais legend, the giant’s role is even replaced by the devil: he, carrying the bell of Sion in a basket, tripped at the summit of Mont Joux. The bell, basket, and demon rolled down to Montigny, where they formed Mont Catagne, whose silhouette resembles an overturned basket.

The legend also attributes a much more mundane geography to Gargantua. The mud from his shoes is said to have created a <strongmultitude of hills: Pinsonneau in Charente-Inférieure, a small mound at Grignon, two hills at Précy-sous-Thil (Côte-d’Or), two mounds in Poitou, and even three isolated knolls at Heuilley-Coton (Haute-Marne).

And the stories become even more colorful: while “farting and pooping”, Gargantua is said to have formed several famous landforms, such as the Pic d’Aiguilhe in the Forez, Mont Gargan near Nantes, his namesake near Rouen, the Pech d’Embrieu near Saint-Céré, and even the Aiguille de Quaix, nicknamed the Gargantua’s Turd. A hill near Carpentras, called the Estron de Dzupiter, seems to share an equally scatological origin.

4. The breaches and the giants

Some spectacular breaches visible in French massifs are attributed not to erosion or earthquakes, but to the sword strikes of legendary heroes. The most famous is undoubtedly the Brèche de Roland, near Gavarnie in the Pyrenees. According to tradition, Charlemagne’s nephew himself split the mountain with a masterful blow.

Another legend tells that one day, annoyed at not having thrown</strong his stone as far as he had hoped, Roland drew his sword and cut through the mountain of Beltchu, leaving a monumental scar that still draws attention today.

In the Alps, it is again Gargantua who leaves his mark on the landscape. In Savoie, near the Grands Plans, he is said to have moved a huge rock to open a passage. The dislodged boulder, still visible on a nearby mountain, would testify to the giant’s enormous strength.

This story fits into the long series of legends in which Gargantua shapes the landforms, sometimes by depositing earth, sometimes by tearing out stones, giving the mountains their uniquely distinctive shapes.

In the Dauphiné, another story links rocky breaches to giants. It is said that a colossus set out to rid the region of a monstrous wolf, reputed to devour men and beasts. But when the animal appeared, with a bloody mouth and threatening fangs, the giant’s courage faltered. Rather than confronting the beast, he struck the side of a mountain with his sword and opened a wide crack to take refuge there. This passage, known as the Saut du Loup, near Sassenage, is still shown as the tangible trace of this missed encounter between human strength and animal savagery.

5. The Devil at Capu Tafunatu

The Capu Tafunatu, in Corsica, is famous for its circular opening visible at sunrise. This hole, impressive and mysterious, is not explained by geology in popular tradition, but by a diabolical legend.

According to the story, the devil, furious after breaking his plow against a rock, threw his hammer with such force that it pierced the mountain. Thus was born the hole of Tafunatu, still visible today, an eternal reminder of this infernal wrath.

Another version places the quarrel at Campotile, on the upper plateau. The devil was plowing his fields when he was interrupted by Saint Martin, who mocked his poorly drawn furrows. Stung, the devil swore that he would “make a furrow so straight that even the saint could not criticize it”. He set to work, but his undisciplined oxen complicated the task. Enraged, he jabbed them with his pitchfork, and in the chaos, the plowshare struck a rock and broke. In anger, the devil hurled the tool into the air. The metal piece flew to Capu Tafunatu, piercing a perfect opening, before falling back into the sea, near Filosorma.

Through these stories, a recurring theme of Corsican folklore emerges: the devil, despite his strength and arrogance, always comes up against the Christian faith embodied by the saints. Here, the hole of Capu Tafunatu becomes both a spectacular natural monument and a visible trace of this mythical struggle between evil and the sacred.

6. Anthropomorphic aspects of some

Leave a Reply