The Man in the Moon: Condemnation of a Sinner

1. Punished for a Religious Offense

Working on the Lord’s Day has never been without consequences… according to the many popular legends from Christian regions of Europe. The lunar body, far from being a mere celestial backdrop, becomes the stage for divine punishment: that of the man (or woman) who refused to observe the Sunday rest.

Across France and beyond, these tales recount how peasants, artisans, or thieves were carried to the Moon, condemned to wander there with the instrument of their wrongdoing. Here is an overview of these lunar legends from Christian folklore.

In many versions, the story is simple: an individual performs work forbidden on Sunday, and God punishes them by exiling them to the Moon. The culprit carries with them the object of their sin: a bundle of thorns, a wheelbarrow, a bucket of laundry, or even an oven not lit in time. These tales, rich in regional variations, serve both as moral lessons and as mythical explanations for the presence of a visible figure on the Moon.

In southwestern France, a Basque version claims that the Moon itself is the punished man. A mother recounts: “A man went to patch a hole in his hedge on a Sunday, carrying a bundle of thorns on his back. Jainco (God) appeared to him and said:

"Since you have not obeyed my law, you shall be punished. Until the end of the world, every night you will shine."

And the man became the Moon.

In the Liège region, the myth takes a cosmogonic turn: the Moon did not exist before the sin. The peasant Bozar, accustomed to cutting wood during Mass, is confronted by an old man:

"There are six days to work, the seventh to pray."

Bozar ignores the warning. Then God declares:

"I will create the Moon and lock you there with your bundle of sticks."

In this version, a man persists in working on holy days. On his third disobedience, God offers him a choice: “Sun or Moon? The sun burns, the Moon bites.” The man chooses the Moon. The story specifies that his name was Février (February), and having refused rest, he will never know it again, condemned to wander on a moving celestial body.

The good man Job, caught patching a breach, first chooses the Sun, but, suffering from the heat, is transferred to the Moon. In Bigorre, a simple bundle-stealing thief suffers the same punishment. In Bourbonnais, several stories mention men and women working on sacred days—Christmas, Easter, Ascension… All end up on the Moon or the Sun, sometimes exchanged during an eclipse, in a cosmic inversion that God ultimately refuses to undo…

Throughout France, the same pattern repeats:

These tales reveal one thing: the Moon is not just a celestial body. It becomes a mirror of human faults, a space of celestial memory. The one who transgresses the sacred rest does not vanish; they are set as an example, visible each night to remind everyone of the importance of observing the sacred rhythm.

2. Biblical origin

In most traditional stories, the Man in the Moon is not alone. He is accompanied by an object—often heavy or sharp—a burden that represents the fault he committed on Earth. In 35 legends out of 50, this object is a bundle of sticks.

The bundle of sticks is not just a tool of rural poverty: it also refers to an original fault—the act of working on the sacred day of rest. This figure is thought to be inspired by the Book of Numbers (XV, 32–36) :

29 For the native Israelite — among the sons of Israel — and for the immigrant residing among them, one single law shall apply to anyone who commits a fault unintentionally.

30 But the person who, whether native Israelite or immigrant, acts deliberately, it is the Lord that they offend: that person shall be cut off from the midst of their people.

31 Since they have despised the word of the Lord and violated His command, they must be cut off — yes, cut off from the people: the guilt is upon them!”

32 While the sons of Israel were in the wilderness, they found a man gathering wood on the Sabbath day.

33 Those who had found him gathering wood brought him to Moses, to Aaron, and to the whole community.

34 They put him under guard, because no decision had yet been made about what should be done to him.

35 Then the Lord said to Moses: “The man shall be put to death: the entire community shall stone him outside the camp.”

36 So, as the Lord had commanded Moses, the whole community brought him outside the camp, stoned him, and he died.

This passage from the Old Testament may have blended with popular legends, giving rise to this figure exiled in the Moon, his bundle of sticks on his back—an eternal reminder of a forbidden act.

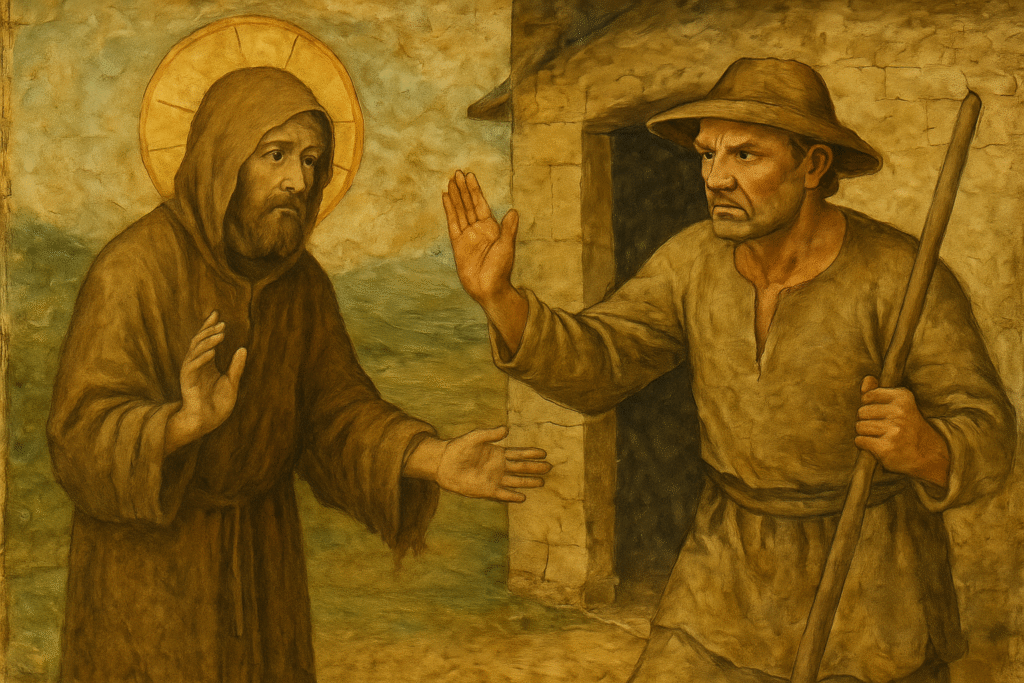

3. Atones for a lack of charity

In French popular legends, the Moon is not merely a poetic star. It becomes the site of an eternal punishment for those who are heartless, selfish, or indifferent to human suffering. And when charity is lacking, especially toward a poor traveler, the sanction is relentless: exile to a cold and fireless star, with only the weight of one’s guilt as a companion.

These stories, found in various regions of France, teach that refusing to help a stranger—especially if it is Jesus disguised as a beggar—can lead to a terrible punishment: being cast onto the Moon, burdened with the very symbol of one’s greed.

In the Bocage Vendéen, it is said that a man refused a spot by his fire to Jesus, who had come incognito. For this fault, he is sent to the Moon, burdened with a bundle of sticks, never able to warm himself. Thus, the fire he denied to others becomes forever out of reach—a cruel and celestial irony.

On the Coast of Côtes-d’Armor, the figure of the damned takes the name Pierrot. This greedy peasant stole his neighbors’ bundles of sticks and refused to share the warmth of his hearth. One evening, a poor old man knocked at his door:

“Move along, my house is not for wanderers!”

The old man calmly replied:

“The wood you burn doesn’t cost you much, but you will pay for it sooner or later. We shall meet again.”

Pierrot repeats his offense with twelve other beggars, all mercilessly turned away. At his death, he finds himself facing them, revealed as the twelve apostles of Jesus Christ:

“There is no place here for you. You will go neither to heaven, nor to hell, nor even to purgatory.

You will be sent to a cold place, with the bundles of sticks you have stolen, never able to warm yourself.

It is on the Moon that you will do your penance.”

At that very moment, Pierrot is cast onto the Moon, condemned to carry forever the stolen wood he refused to share.

These stories are not isolated. In Lower Normandy, tradition identifies the Man in the Moon as the rich wrongdoer, the one who, despite his wealth, offered nothing to the poorest. Thus, the Moon becomes the symbol of a moral cooling—a frozen purgatory, suspended in the sky.

Whether it is a simple refusal, a theft, or a closed heart, the lesson remains the same: what we refuse here on Earth will be denied to us in the afterlife. Lunar exile is less a physical punishment than a spiritual allegory: those who refuse the warmth of sharing will experience the eternal cold of solitude.

4. Thief sent to the Moon

Among the many European legends surrounding the Man in the Moon, some depict him as a shadowy thief, punished for his nocturnal misdeeds. The lunar body then becomes a place of exile, of silent suffering, reserved for those who have transgressed human or divine laws—often through poaching or stealing wood.

In the Perche region, it is said that the Man in the Moon was the first thief on Earth. God placed him in the sky, on the Moon, to serve as an example. A 12th-century Latin quatrain summarizes him with poetry and severity:

Rusticus in Luna – Quem sarcina deprimit una – Monstrat per opinas – Nulli prodesse rapinas

(The peasant on the Moon – crushed by his load – shows everyone that – theft benefits no one.)

— Alexander Neckam, De naturis rerum

In Upper Brittany, another version illustrates divine justice through a direct enactment. When a man steals a bundle of sticks, God intervenes:

“These bundles of sticks are not yours. I could make you die. But I give you the choice: after your death, do you wish to go to the Sun or to the Moon?”

The man, cunning, replies:

“I prefer the Moon. It only comes out at night; I will be seen less often.”

The sentence is final: he remains there until the last day of the world, unable to die.

In a Walloon legend, a man named Bazin steals at night in his neighbor’s fields. Caught in the act, he tries to frighten him:

“ I come from the grave, in the name of the living God, to take away both the young and the old! ”

But God is not fooled: Bazin is condemned to wander on the Moon, bundle of sticks on his back. He remains there, his face twisted with regret, gazing melancholically at the Earth. A popular expression from Liège preserves this memory:

It’s like Bazin on the Moon

he has what he deserved.

In Lower Normandy, the story of a thieving peasant once again illustrates divine strictness. He would plunder his neighbors’ hedges, especially between Saturday and Sunday. On his way home, burdened with a bundle of thorns, he encounters people who accuse him:

“Old man, have you been stealing our wood again?”

He swears: “By my faith, may I be on the Moon if you lie!”

No sooner had he spoken than he disappears into the Moon, caught by his own words. In this version, the Moon seems alive, endowed with will, capable of swallowing the guilty itself.

According to historian Oscar Colson, in some cultures, the Moon was not merely a celestial backdrop, but a punitive deity, watching over nocturnal transgressions. He suggests that over time, God may have replaced the Moon in these stories to align them with Christianity:

“God would have taken the place of the Moon, which appeared in early lessons of punishment for nocturnal marauders.” — Wallonia, 1893

Until the beginning of the 20th century, popular Walloon expressions bear witness to this ancient belief:

Jusqu’au début du XXe siècle, des expressions populaires wallonnes témoignent de cette croyance ancienne :

Whether it is Bazin, the Norman peasant, or the overconfident Breton man, the message remains clear: theft, especially committed at night, never goes unpunished. And the Moon, a celestial and icy mirror, preserves the trace of these condemned souls, perhaps visible in the shadows of its craters.

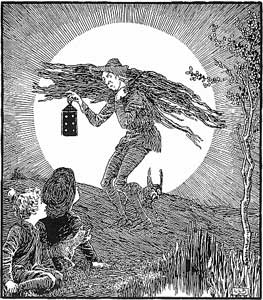

5. The Moon that takes revenge or delivers justice

Throughout the West and North of France, as well as in Wallonia, the Moon is more than a celestial body. It is a judge and executioner, watching from the night sky over thieves, liars, and perjurers. Popular legends describe it as alive, sensitive to offenses, capable of engulfing the guilty… often for eternity.

In Brittany, several stories follow the same dramatic pattern: a man accused of theft denies the charges by invoking the Moon. It proves disastrous for him. In the first story, a lord accuses a peasant of stealing gorse bundles from his heath. The peasant swears:

“May the Moon swallow me if I took them from your land!”

He was lying: the Moon immediately swallowed him. Since then, Breton fathers show the dark figure visible on the Moon to their children, saying:

“Al laèr lan” — the thief of the heaths.

A version from southern Finistère follows the same motif, set in contemporary times: a man is brought before the mayor, accused of cutting gorse on common land. He exclaims:

“May the Moon swallow me if I have stolen this heath!”

And, at that very moment, the Moon descends from the sky and swallows him.

And, at that very moment, the Moon descends from the sky and swallows him.

In another tale, a man steals bundles of sticks at night. Caught in the act, he declares:

“May the Moon take me if these bundles of sticks are yours.”

The Moon does not hesitate: it takes him immediately, condemning him to carry his burden until the Last Judgment.

Even a child who steals eggs does not escape celestial rigor if he dares such an oath. Another peasant, accused of stealing the bundle meant for the St. John’s fire, exclaims:

“May the Moon swallow me if I took it!”

The Moon swallows him without delay.

In these legends, the Moon acts on its own, without divine intervention, as an autonomous power. In Wallonia, this idea is widespread: the Moon punishes lies, false oaths, or insults.

The thief Bazin, a recurring figure in Walloon tales, one evening tries to steal hay under the cover of darkness. But the Moon betrays him by shining all at once. Spotted, Bazin, furious, exclaims:

“May the six hundred thousand devils take it!”

The Moon, offended, makes him disappear with his bundle of hay. It is said that his shadow is still visible up there.

In the Belgian Ardennes, a young girl, passionate about dancing, had promised her mother to return before midnight. She swears:

“As surely as the Moon lights our way!”

But she forgets her promise. Her mother finds her near the cemetery and calls out to her. The girl, startled, exclaims:

“To hell with the Moon!”

Immediately, she is taken by the celestial body, condemned to endlessly weave the threads of the Virgin, sometimes visible from Earth.

Another, gentler version recounts that the mother, seeing her daughter dancing late, offers a prayer to the Moon, asking it to punish the forgetful child. The Moon answers the prayer: the eternal spinner is born.

The Moon does not punish only lies; it also watches deeds. In the Dauphiné, a barber named Bazin attempts to steal wood for the St. John’s fire, atop a mountain. He is swallowed by the Moon, the sole witness to the crime.

In Lorraine, another figure illustrates lunar wrath: Jean des Choux, nicknamed Jean of the Moon, steals his neighbors’ cabbages. One night, the Moon watches him. To avoid being heard, Jean greases his wheelbarrow with urine. The Moon continues to fix its gaze on him. Exasperated, Jean insults it. The response is immediate: he is sucked up by the celestial body, condemned to push his wheelbarrow forever across the lunar surface.

In some tales, thieves try to get rid of the moonlight, which betrays them. In the Hainaut, a man named Pharaon, caught stealing turnips under the Moon’s rays, attempts to <strong:block it with a bundle of thorns. God prevents him: he is drawn into the Moon. In the Vosges, Gossa, a persistent thief, climbs up to the Moon to extinguish its light. But he remains stuck there for eternity. Another story features Judas Iscariot. Harassed by the celestial body, he exclaims:

« *Open eye watching me, I’ll gouge you out!* » He climbs up to the **Moon**, tries to wound it with a bundle of sticks, but an **invisible hand** pins him there **forever**.

In all these legends, the Moon is a moral force, relentless and punishing, sensitive to disrespect, lies, and perjury. It sees, it hears, and forgets nothing. It is easy to understand why the oath “May the Moon swallow me!” was taken seriously in the countryside—a warning that was at once poetic, tragic, and symbolic.

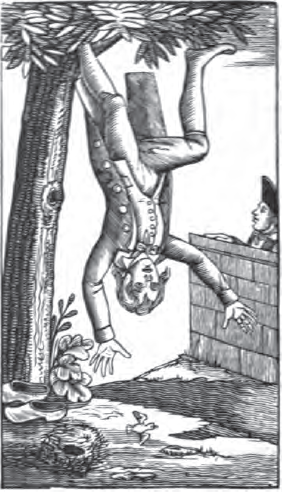

6. Judas, Cain, and the Wandering Jew

Judas Iscariot, the ultimate traitor, is an ever-present figure in lunar legends from eastern France. After betraying Christ, he finds no rest: his punishment is celestial, spectacular, and endless.

Judas Iscariot, the ultimate traitor, is an ever-present figure in the lunar legends of eastern France. After betraying Christ, he finds no rest: his punishment is celestial, spectacular, and endless.

In the Aube, children are told:

“Do you see Judas on the Moon, with his bundle of thorns?”

He is up there, suspended in his torment, bearing the symbol of his guilt.

In the Morvan, he is associated with a basket of stolen cabbages, emphasizing the link between betrayal and theft. In Saint-Pol (Pas-de-Calais), he is depicted hanged by the hair or feet from a elder tree. The same tree appears in the Marne, where it is said that Judas hanged himself on the Moon, among its branches.

One of the most detailed versions comes from Franche-Comté. After his death, the celestial council hesitates over Judas’s fate, unable to place him in any known category of the damned.

Judas then declares arrogantly:

“Wherever you place me, I will not be alone.”

To which God responds:

“Then you shall be placed on the Moon, where you will be alone. For no one else has ever been there, is there, or will ever be.”

His torment takes a physical form: his head is trapped between two bundles of thorns. From this comes the local expression: “To be like Judas on thorns”, used to describe a very uncomfortable situation.

In this same region, children, when looking at the Moon, sing a cheeky rhyme:

“Voilai la lenne – Due lai proumène – Voilai Judas – Merde pour son nâ”

“Here’s the moon – May it walk – Here’s Judas – Damn his birth”

(reported by Charles-Alexandre Perron, Proverbs of Franche-Comté, p.139)

And if a child spits in another’s face, people exclaim: “Judas on the Moon!”

In Belgian Luxembourg, the Moon does not harbor Judas, but Cain, the murderer of his brother Abel. It is said that he flees the sunlight, ashamed of his crime, and hides in a bush. The spots on the Moon are then interpreted as the parts of his body he could not conceal: eyes, nose, ears, and mouth.

An alternative version states that Cain is condemned to push a cart on the Moon until the end of the world, a fate reminiscent of the Lorraine thieves. In Laroche (Marne), he carries on his back a perpetual bundle of sticks, symbolizing his guilt.

In Guingamp and along the coast of Côtes-d’Armor, it is neither Judas nor Cain, but the Wandering Jew who is seen on the Moon. Condemned to celestial immobility, he gathers bundles of sticks each day, with the purpose of setting the Earth ablaze on the Last Day. In these legends, the Moon becomes the reservoir of apocalyptic fire, containing the final punishment to come.

In certain regions, the Moon is not merely a celestial prison; it is directly linked to infernal forces: In Ille-et-Vilaine, God creates the Moon to shine only at night, so that it does not warm the Earth like the Sun. But the celestial body eventually comes to harbor the fallen angel, armed with a pitchfork—an implement forbidden on Sundays, which has become one of the Devil’s attributes.

In Upper Brittany, the Devil is the Man in the Moon, carrying the damned souls on the tip of his pitchfork, which he casts into the eternal fire. In the Côtes-d’Armor, he gathers bundles of sticks to feed the infernal blaze.

Judas, Cain, the Wandering Jew, the Devil… All these legendary figures inhabit the Moon in popular imagination, serving as visible symbols of human guilt. The Moon is no longer a mere nocturnal star: it is the cosmic mirror of sin, the prison of guilty souls, the sentinel of the Last Judgment.

7. Lunar Pareidolia

Over the centuries, the Moon has been given a face. Not just a gentle or romantic one, but a mask burdened with sins, a celestial mirror reflecting human faults back to the eyes of the living. Today, one can see only the swollen features of Cain and the grimacing face of the Devil.

In ancient imagination, the Moon observes, watches over, follows with its gaze. It is no longer a simple celestial body, but a cosmic eye of punishment. It is described as a great face turned toward the Earth, whose dark patches are as many stigmata of crime.

The Shepherds’ Almanac, in the edition of Mathieu Laensberg, speaks of a swollen face, distorted, almost grotesque. And people used to say of those with puffed cheeks or a pale complexion that they looked like the Moon. This image likely comes from the mischievous grimaces drawn by early popular illustrators, in which the celestial body was already caricatured as a human face, mocking and unsettling.

The spots on the Moon, formed by the lunar seas and the shadows of the craters, give rise to strange visions. Depending on the tilt of the Earth, the pareidolia shift: a burdened man, a weaving woman, a thief loaded with bundles of wood, a punished child.

These optical illusions, interpreted according to one’s culture, reinforce the idea that the Moon is not empty, but inhabited by symbolic figures. In popular traditions, these shapes are rarely innocent: they embody guilt, shame, or damnation.

In the Bourbonnais, mothers knew how to turn these tales into gentle educational tools. To calm their unruly children at bath time, they whisper a phrase that is both tender and unsettling:

“Look closely at the Moon; it is a dirty child who refused to wash up.”

Thus, the Moon becomes a warning. It shows what one becomes when one refuses order, cleanliness, or obedience. Even the youngest learn to see a reflection of their behavior in the night sky.

Popular tales do not merely punish faults with cold, loneliness, or endless toil. They inflict a moral torment: the shame of being seen, exposed constantly to everyone’s eyes.

This feeling of shame is so intense that, in a Breton legend, the thief prefers to be locked in the Moon rather than exposed in broad daylight:

“He chooses the Moon rather than the Sun.”

The Sun, blazing, exposes the truth too harshly. The Moon, discreet yet ever-present, casts a subtler light, but one that is just as relentless.

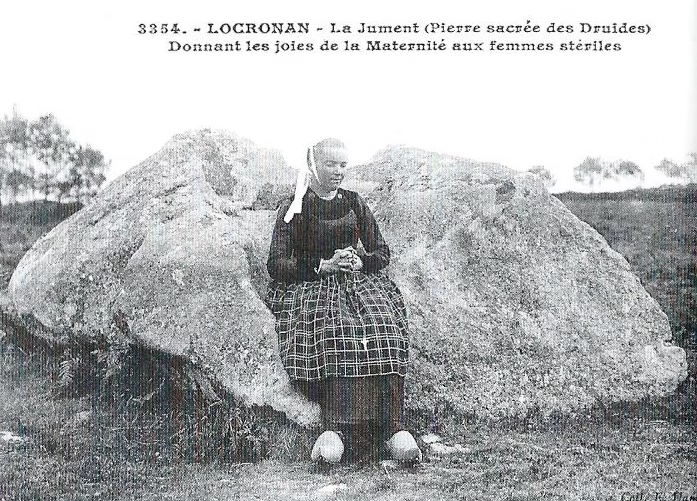

8. Various Legends of Characters Taken by the Moon

In ancient beliefs, the Moon is not merely a cold and distant celestial body. It is a place of banishment, a suspended purgatory, a celestial mirror where the souls of the guilty, the careless, or the irreverent are projected.

On the shores of the Bay of Saint-Malo, an old tale recounts the strange fate of a captain. His wife, rescued from drowning, was led by him to the salt quarries as a gesture of gratitude toward the Sea. But in doing so, he crossed an invisible boundary: the Sea, subject to the Moon, was not to be subjected to the salt of men.

The Moon herself appeared to the captain. She reproached him for this act. And to punish him for salting the waters she governs, she took him away, condemning him to wander forever within her celestial realm. Some say he ascends with a sack, like another miller from Beauce, burdened with a similar fate.

In Lower Brittany, a ragpicker, or pilhaouer, came across a mysterious circle on his path. Spirits were dancing there, singing:

"Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday !"

Caught up in the moment, he added to the rhyme:

“Saturday and Sunday after!”

But his intrusion proved fatal. The dragons of the wind carried him, sack on his back, up to the Moon. There, he was frozen among the stars as punishment for invoking the holy days forbidden for dancing. Yet all is not lost for him: he will be freed if another, by chance, repeats the same phrase to the spirits. A form of redemption suspended on the whim of words.

In the Perche, a tale blends humor and the fantastic: François de La Ramée, a cunning soldier, managed to capture the Devil. He placed him in a sack, had a gigantic cannon built, and aimed it at the sky. With a thundering shot, he sent Satan to the Moon, where he arrived in less than a minute. This tale gives another face to the nocturnal star: no longer the tomb of sinners, but the prison of the Evil One.

Elsewhere, people continue to discern shapes in the Moon’s spots. In the Pays mentonnais, one can see three figures and some brambles. In Lower Brittany, an old priest claimed to see Adam and Eve, exiled up there after their death. In the Bourbonnais, children swear they see a gardener planting cabbages, or a man pulling a large rat by its tail. In Martres-de-Veyre, it is Gargantua.

In Lunéville, the figure visible in the Moon is said to be that of Michel Morin, a sexton with legendary skill in making bundles of sticks, whose story was spread in a popular Vosgian eulogy; the legend is intertwined with a Saracen diabolization and a lineage connected to the giant Mory (see Mythologie française, Henri Dontenville, Maures et Sarrasins).

Each of these lunar pareidolias is a moralized figure, turning the Moon into a living tableau of our mistakes, our pranks, or our defiance of invisible powers.

Whether it is a captain in exile, a ragpicker carried away, a devil dispatched, or mythical beings trapped in the pale light, all these stories share an ancient belief:

The Moon is not empty. It is full of stories, of sins, of sacks too heavy, and of careless words.

It is the night-time memory of the world, where the silhouettes erased by the Sun are recorded.

9. Accessories of the Man in the Moon and His Names

Other objects appear in regional tales, all linked to the nature of the offense: the wheelbarrow, in Lorraine, used to carry stolen goods. In the Luxembourgish legend, it was first that of a simple thief, before becoming the torment of Cain. The basket of cabbages in the Morvan, and the bundle of cabbages on the island of Sein, recall rustic thefts. The satchel, in Morbihan, Beauce, or Perche, evokes the working tool of peddlers or wanderers, often associated with minor pilfering.

In many regions, wood stolen at night is nicknamed “Moonwood”, so much does the act seem already under her gaze and judgment. And the thief does not steal only wood: sometimes it is eggs, vegetables, or hay. The culprit can even be a child, in the moralizing versions told to the young to encourage obedience.

Paul Sébillot, a major collector of oral traditions, reports that many storytellers learned this tale from their mother, who would tell it while pointing to a particular thief in the village. The story then took on a social function, serving to stigmatize or educate.

The lunar character changes names depending on the province, often with mocking, pejorative, or simply local nicknames:

| Nom | Région | Signification |

|---|---|---|

| Bernat the Fool | Languedoc | Simple Contempt |

| Matièu, the Woodcutter | Provence | Direct Allusion to the Crime |

| Brûno | Namur | Popular Variant |

| Nicodème | Ille-et-Vilaine | Corrupted Biblical Name |

| Pierrot | Côtes-d’Armor | Derived from Pierrot of the Moon |

| Jean of the Moon / of the Cabbages | Lorraine | Agricultural Theft |

| Tchun dél lœn | Wallonia | “Moon Dog” in dialect |

| Basi | Dauphiné, Belgium, the Metz region | Familiar name |

| Jean the Huguenot | Aurillac | Mark of religious exclusion |

| Bouétiou le boiteux | Puy-de-Dôme | Mild ridicule or childish twist |

In the Metz region, they say with irony:

« Çat l’Chan Basin aiveu s’ féchin » – « Here is Jean Basin with his bundle of sticks. »

In Aurillac, the name Jean le Huguenot refers to a religious demonization: Protestantism seen as heresy. In Puy-de-Dôme, Bouétiou can be understood as a form of pity or a designated accomplice. When a child asks an awkward question, adults reply evasively:

« Bouétiou dins lo liuno »

A lunar non sequitur, equivalent to the French: “Have you seen the Moon?”

Leave a Reply