Cults and Observations on the Rocks

1. The Slide and Love

Even before the erection of megaliths, certain religious practices took place around natural boulders, without any human intervention. These rites, often rough or puzzling, are now classified as pre-megalithic cults. Sliding is the most emblematic example. It is characterized by the voluntary—sometimes forceful—contact between the believer’s body and the stone, which is attributed with particular virtues.

The most numerous examples concern young women wishing to marry. In northern Ille-et-Vilaine, several rocky boulders bear the evocative name of "Crying Rocks". Young women would climb them to slide all the way down — écrier in the local dialect — in order to hasten their marriage. Repeating the rite sometimes polished the stone’s surface itself, a material testimony to centuries of secret practices. In Plouër, young women had, since time immemorial, practiced the ritual of "s’érusser" on the highest block of white quartz at Lesmon, shaped like a rounded pyramid. Before sliding, they had to hitch up their skirts: if they reached the bottom without injury, marriage was guaranteed within the year.

On the Roche Ecriante of Montault (Ille-et-Vilaine), tilted at 45°, the marks left by the sliding were still visible. After the ritual, out of sight, the young woman had to place a piece of cloth or ribbon on the stone. Similar practices existed far beyond Brittany:

It was said that, on the night of May first, young women would climb the great menhir, hitch up their skirts and chemise, and let themselves slide down in hopes of a quick marriage. Sliding was rarely practiced on actual megaliths due to their vertical nature. One exception, however, is mentioned at Locmariaker (Morbihan). This menhir, now broken into four pieces, was still standing in the early 18th century. The practice described is therefore relatively recent, but it may be the survival of a much older rite once carried out on a nearby natural rock.

In Walloon Belgium, the rite had evolved into a more playful ceremony. On the Ride-Cul rock, near a chapel nicknamed Notre-Dame de Ride-Cul, a pilgrimage was held every year on March 25. Boys and girls would sit on the stone, placed on bundles of twigs, and slide down. Any mishaps during the descent served as omens:

"If there is a retournade (interrupted slide), it means one must wait;

if there is an embrassade, it means one is in love;

if there is a cognade (collision), it means one does not love each other;

if there is an embrassade followed by a rolling, it means they are suited for each other."

The trial could only be attempted once.

Near Hyères, the Slippery Stone seems to be the faint remnant of an ancient rite. Young women would place a myrtle bouquet on its summit. Eight days later:

In several villages of the Aisne, there was a Bride’s Stone. On the wedding day, the bride had to sit on it on a wooden clog and slide down. Depending on how she reached the ground, the villagers drew conclusions, often expressed in a bawdy manner. If the clog broke, the cry resounded: “She broke her clog!”

An expression which, elsewhere in France, meant to have lost one’s virginity.

This rite, almost always linked to love, could also concern motherhood. In the Ain, at Saint-Alban, near Poncin, pregnant women would slide down an inclined rock to ensure a happy childbirth. In the Valais, finally, shepherds would slide on the Pirra Lozenza, near the Fairy Stone, adorned with prehistoric carvings—probably the last playful echo of an ancient ritual use.

2. Friction and Fertility

Founded, like sliding, on a deep belief in the supernatural virtue of stones, the practice known as friction is distinguished by its more clearly phallic and symbolically fertilizing character. Whereas sliding involved contact with the posterior part of the body, friction engaged in a direct rubbing, often naked, of the navel, the abdomen, or—even most likely—the genitals themselves. Ancient observers often described this rite with caution, or even understatement, given the explicitness of its symbolism.

Some natural stones, or those erected by human hands, featured a rounded or oblong relief, whose shape roughly evoked that of a phallus. It is likely that this aspect suggested the ritual gesture performed upon it. Originally—and perhaps even into the 19th century—friction was perceived by believers as a bodily offering, a kind of sacrifice to the spirit of the stone.

While sliding gave women a jolt comparable to a “roller coaster,” rubbing against the consecrated part of the stone could awaken sensations of another kind, closely linked to fertility.

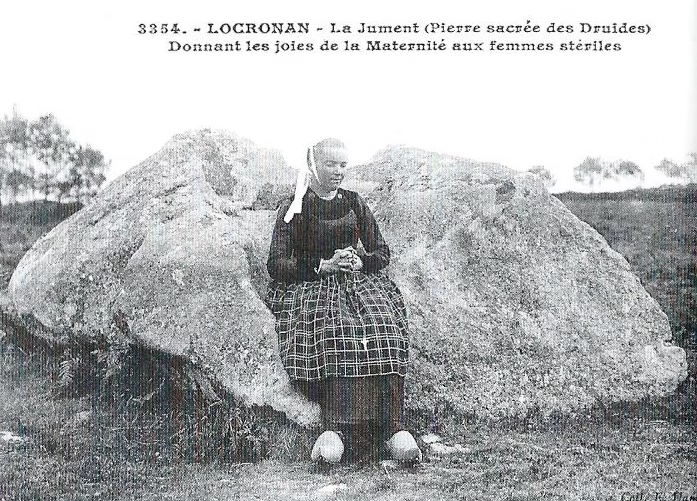

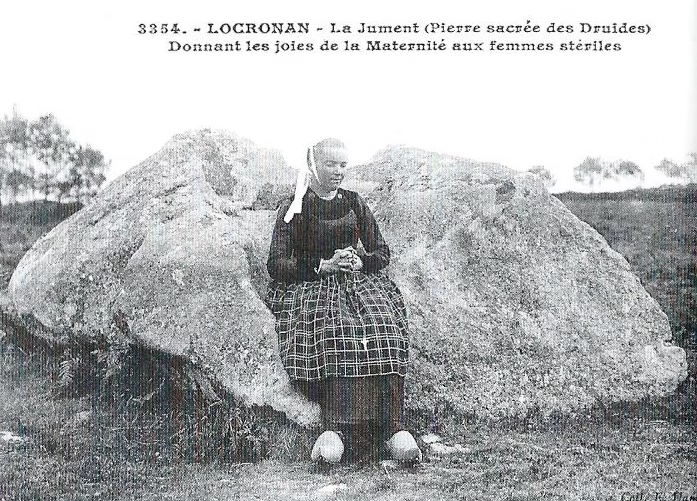

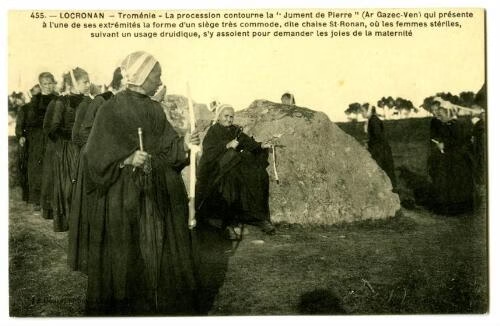

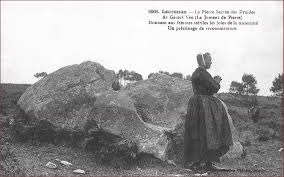

Unlike sliding, friction seems to have been more often practiced on intentionally erected blocks than on mere surface rocks. This distinction becomes even clearer in the study of cults associated with megalithic monuments. At Saint-Renan (Finistère), young brides would, until recently—and perhaps still today—rub their bellies against the Stone Mare, a colossal rock erected in the middle of a moor. Its silhouette evokes an animal from fabulous times, undoubtedly reinforcing its symbolic power. The purpose was clear: to have children. At Sarrance (Lower Pyrenees), women who suffered from being childless performed a similar gesture. They would reverently pass over and over a small rock called the Rouquet de Sent Nicoulas, hoping thus to overcome sterility.

Friction on stones was not limited to matters of love or fertility. It was also practiced to gain strength or regain health. The most significant examples were observed in Breton-speaking regions, where certain stones bear a doubly evocative name:

At Pleumeur-Bodou (Côtes-d’Armor), to give strength to children, their lower backs were rubbed against the Saint-Samson Rock, located near the chapel dedicated to this saint. At Trégastel, a rock of the same name featured a deeply worn notch from pilgrims, tangible proof of the gesture being repeated across generations. In the chapter devoted to megaliths, several menhirs, also called Saint-Samson, are noted as being the object of similar practices.

3. Marriage Stones

Other stones were associated with ancient wedding customs, and some, like the Bride’s Stone of Graçay (Cher), on which the newlyweds would dance on their wedding day, bore a name reflecting this purpose.

In the village of Fours, in the Lower Alps, a conical-shaped rock was called the Bride’s Stone, to which the groom’s closest relative would lead the bride after the religious ceremony; he would seat her there himself, carefully placing one foot in a small hollow of the stone that seemed to have been made on purpose, although it was naturally formed. It was in this position that she received kisses from all the wedding guests (Alfred de Nore, who in his Customs reports the same ceremony, says that the bride placed her right foot there, the left remaining suspended).

In the vicinity of Sorendal, in Belgian Luxembourg, the bride and groom were led, at nightfall, to the marriage stone, where they would sit back to back.

4. Body Contact with the Blocks

Sterile women would also seek fertility from certain stones; in Decines (Rhône), they would formerly squat on a monolith placed in the middle of a field, at a place called Pierrefrite, which was perhaps a menhir; in Saint-Renan (Finistère), until recently, they would lie down for three consecutive nights on the “Stone Mare” of Saint Ronan, which is a colossal natural rock.

In the 16th century, a statue bearing the name of a saint, with several variants (Greluchon, Grelichon, Guerlichon, etc.), to which a phallic significance was attached, was believed to have the same fertilizing virtues as these stones. Here is how a writer of that time describes the pilgrimage to which it was dedicated:

Saint Guerlichon, who resides in an abbey in the town of Bourg-dieu, near Romorantin, and in several other places, boasts of impregnating as many women as come to him, provided that during the time of their novena they faithfully lie in devotion upon the blessed idol, which lies flat, and not standing like the others. In addition, it is required that each day they drink a certain brew mixed with powder scraped from some part of the idol, and likewise from the most indecent part, too shameful to name.

Other acts performed in the immediate vicinity of large blocks are believed to have virtues similar to those that put the believer in direct contact with the stone itself. Husbands who are mistreated or made unhappy by their wives—or, according to others, those who fear being cheated—walk on one foot at night around a rock in Combourtillé (Ille-et-Vilaine). In Villars (Eure-et-Loir), horses suffering from sores are made to circle a rough stone in a field called the Perron of Saint Blaise.

Stone fragments are no less powerful than the large natural blocks or megaliths from which they originate. Love, fertility, physical vigor, or protection against illness. Some stones were reputed to promote love and marriage, to the point of becoming true amulets. In Picardy, young women were told:

« Vos vos marie-rez ech’ l’année ci, vos avez des pierres ed’ capucin dans vo poche. »

"You will marry this year if you have Capuchin stones in your pocket."

This expression referred to a popular belief that any young girl who collected a small piece of the stone on which a Capuchin, imprisoned in the Great Tower of Ham, had left his mark would marry before the end of the year. In the Beaujolais, women suffering from sterility would scrape a stone placed in a chapel isolated in the middle of the meadows. In Saint-Sernin-des-Bois, they would scrape the statue of Saint Freluchot (Gervais), seeking in the very material of the saint a hope for fertility.

Near Namary, in the commune of Vonnas, in the Ain, a stone located in a vineyard was gradually reduced to a small size, so much material was taken from it. Men drank the stone dust, mixed with certain beverages, in order to increase their virile strength.

Other, more discreet practices took place under the cover of night. Some women would go at specific hours to a wood near Selignat, where a particular stone was located. After invocations, they would break off pieces of it, which they administered, mixed into a beverage, to their husbands or lovers.

Stone fragments were also used in the field of folk medicine. To facilitate childbirth, believers would take pieces of a stone that once existed in Avensan, in the Gironde. To be protected from illness, pilgrims collected a fragment of the Caillou de l’Arrayé, visible on the road to Saint-Sauveur, in the High Pyrenees, a stone already believed to possess protective and therapeutic powers.

5. Offerings to Stones

Offerings to natural blocks seem less numerous than those made to megaliths, which are believed to have similar powers. Young women who, to find a husband, slid down the Crying Rock of Mellé (Ille-et-Vilaine) were required to place a small piece of cloth or ribbon on it. When taking children whose backsides are underdeveloped to a large stone in Saint-Benoît, near Poitiers, it is essential to throw a few coins, in an odd number, into the hole of this stone, where the little patient is seated.

Mothers would take children with bowed legs, malformed feet, and other similar infirmities to the Saint-Maurice Rock, in the Griseyre forest (Haute-Loire); this pilgrimage is recorded in 1550. In the 19th century, they would kneel, place the child in a crevice of the rock, recite three times the invocation “Saint Maurice, have mercy, heal him!”, slip an offering under the rock, carve a cross on the bark of a nearby pine, and then depart. The sine qua non condition for the child’s healing was that the first passerby would take the offering, kneel in turn, and pray.

In Haute-Savoie, women who wished to become mothers would offer food to the fairies that appeared near a group of rocks, called the Synagogue; if the offerings left in the evening had disappeared by the next morning, the request was granted.

6. Virtues of Waters

Natural waters are believed to possess therapeutic virtues. Among them, those that stagnate in rock depressions or basin stones hold a special place in popular imagination, often compared to miraculous fountains. Water that has rested in stone cavities was attributed a healing power. In contrast, water that drips slowly from rocks did not always enjoy the same reputation.

A notable exception is reported in the village of Hure, near La Réole. There, a rock formation with strange stony concretions, apparently resembling elongated breasts, was the focus of specific therapeutic practices. Nurses would soak a cloth in it and then apply it to their breasts, hoping to stimulate milk production. Others used the same water to rub their eyes, in order to treat various eye ailments. These practices demonstrate a close relationship between the symbolic shape of the stone and the virtues attributed to it.

Another, even rarer practice appears to originate directly from ancient cults. It consisted of anointing the stones with fats, considered pleasing to the deities believed to inhabit or manifest in these blocks. This is the only recorded practice in France directly linked to large natural stones. In the past, the inhabitants of Ota, in Corsica, would gather at a specific time of year to <strong.tie a huge rock overlooking their village. They would pour oil over it, convinced that this ritual would prevent the stone from collapsing onto their houses.

7. Paid Homages

In the High Pyrenees, guides and passersby had the custom of kissing, while making the sign of the cross, the Caillou de l’Arrayé — literally “the torn stone.” This rock overlooks a huge landslide on the road to Saint-Sauveur. According to local tradition, the Virgin rested there during her visit to the region, giving the stone a sacred character. Similarly, the Cailhaou de Sagaret, in the Luchon region, was the object of genuine veneration, reflecting a lasting attachment to stones perceived as bearers of a sacred presence or memory.

In Saint-Gilles-Pligeaux (Côtes-d’Armor), at the center of the Roc’hl a Lez (the Rock of the Law), now broken since 1810, there was a hole said to hold the post supporting a movable dome. It was under this shelter that judges would gather to administer justice. In the vicinity of Arinthod, the Selle à Dieu, destroyed in 1838, was a rough, isolated stone in a vacant lot. Its peculiar shape — narrower in the middle, like a stemmed glass — provided a naturally formed seat. According to local tradition, the judge of the region would formerly sit there to hear the cases of the people.

In the department of Aisne, several natural stones are mentioned as places where justice was administered in the Middle Ages, and even at periods relatively close to our own. Among the best known are a large flat rock, still visible around 1850 in Dhuizel, in the canton of Braine, as well as the Pierre Noble in Vauregis. From the 16th to the 18th century, legal acts sometimes bear the peculiar note: fait auprès du Grès qui va boire (“made near the Sandstone that drinks”), evidence of the symbolic importance of these natural markers in administrative and judicial practices. Finally, people would formerly pay fealty and homage at the chapter of the Chartres Cathedral at a place called Pierre de Main verte, where four or five large stones in the middle of a field still stand, silent remnants of ancient rituals of allegiance.

8. Stone Dust

Leave a Reply