Sun: Savior Star

1. Similarities with the Moon

In several oral tradition stories, the Sun is perceived as a powerful lamp, driven by an invisible mechanism or guided by supernatural beings. It travels across the sky above a motionless Earth, illuminating the living with its beneficent light.

The Sun is also the carrier of the Earth’s warmth, essential to life. In Upper Brittany, it is considered a creation of God, while the Moon is said to be a work of the Devil—less bright, and therefore supposedly more harmful. In other regions of France and in Wallonia, the creation of both celestial bodies is attributed to God alone.

Popular tales often personify the Sun and the Moon, assigning them genders (one masculine, the other feminine) and a conjugal relationship. In Limousin and Belgian Luxembourg, they are even viewed as husband and wife. According to one legend: “You, Sun, will be the husband, and you, Moon, the wife. Sun, you will light the world in the morning, and the Moon in the afternoon.” But the Moon gradually encroached upon the Sun’s hours, provoking his anger. As punishment, God decreed that the Moon would shine only at night.

In the south of France in the 19th century, a belief held that God had created two suns. The second one, having become unnecessary, was transformed into the Moon.

In Rouergue, Languedoc, and Comtat Venaissin, it was said that the Moon was a “worn-out sun”, as confirmed by an Occitan saying:

La Luna era un vielh sourel autres cops :

Quand valé pas res per lou jour,

La metterou per la nioch.

In french:

La Lune était un vieux soleil autrefois :

Quand il ne valut plus rien pour le jour,

On le mit pour la nuit.

Ce qui se traduit par :

The Moon was once an old sun:

When it was worth nothing for the day,

They put it to serve the night.

In Nîmes, it is humorously said that the Moon is a sun that has lost its wig—its rays. In Hainaut, some nickname it a “Retired Sun”.

Sailors and peasants—especially in Ille-et-Vilaine—often believe that the Sun and the Moon are of the same size, although smaller than the Earth. This belief is reinforced by the fact that during an eclipse, the two bodies appear to perfectly overlap. In this popular view, the Sun and the Moon are two flat discs, rather than spheres, as science would later confirm.

2. Personified Sun: Names and Epithets

Everywhere, the Sun is given a proper name, affectionate or whimsical:

In many regions, the Sun is not just a luminous disc; it acts, feels, and interacts with the living:

In Upper Brittany, it is said that the Sun has legs when its rays graze the earth.

In Morbihan, if the sky is dark, it is said that “the Sun is ashamed”. And when its rays timidly pierce the clouds, the villagers exclaim:

“Here is the Sun wanting to show us the tip of its nose”.

Finally, a saying from Ille-et-Vilaine reminds us that appearances can sometimes be deceiving:

“If the Sun laughs white in the morning, it laughs black in the evening” — a sign that a beautiful sunrise can foreshadow a storm at dusk.

3. Role in Popular Tales

In many Breton legends, the Sun descends to Earth and takes human form: in Upper Brittany, it is said that it once came down to Earth, burning it in its path, much like Phaeton in Greek mythology.

The folklorist François-Marie Luzel collected in Lower Brittany a cycle of tales entitled Journeys to the Sun. In these stories, we encounter a Sun in love, taking human form to marry a young Earth woman. He takes her to a subterranean palace or the Castle of the Rising Sun, where she lives fulfilled but alone during the day:

“For her husband leaves before dawn and returns only at dusk.”

A more developed version tells of a shepherdess, enchanted by a young man so radiant that she believes she is seeing the Sun in person. He abducts her after the wedding, in a chariot to the Crystal Castle, located across the Black Sea. In Upper Brittany or Ille-et-Vilaine, variants follow the same pattern: a radiant man, absent during the day, returns only at nightfall, leaving the mystery of his double life.

In some tales, adventurers set out to meet the Sun: its home is located on a high mountain or beyond a river separating the world of the living. When they ask it: “Why are you so red in the morning?”, it replies that it is to avoid being outshone in beauty by the Princess of Tronkolaine, whose castle is nearby.

Another version tells of the Enchanted Princess, who stands at her window to watch it pass—explaining the rosy glow of dawn. But at dusk, the hungry Sun becomes an ogre: it wants to “devour a Christian whose scent it senses,” often introduced by its own mother.

This monstrous side of the Sun is reinforced by the figure of Grand-Sourcil, a giant living inside a rock as bright as a star. He too disappears during the day, making him an incarnation of the Sun itself (a tale from Upper Brittany).

But not everything is dark. Sometimes, the Sun gives advice to humans. To a man who was too reckless, he simply says: “Stay away from my dwelling, unless you want to burn.”

In a rare but fascinating belief from Upper Brittany, paradise is said to lie within the Sun.

The ancient peasants and sailors did not believe in the Sun’s immobility. For them, the Earth is fixed, and the Sun travels across the sky: the Channel sailors believe that it sets in the sea to regain its strength there, before shining again the next day. The Provençal book Les Enseignements de l’enfant sage by Raymond Lulle (1233–1316) states that once the Sun has disappeared, it gives its light to Purgatory, to the sea, and then to the East.

In the 18th century, in the Limousin countryside, people said that it traveled during the night from its setting to its rising.

Fishermen from the Bay of Saint-Malo say that when it plunges into the sea, it produces a rumbling sound like red-hot iron plunged into water. On the Tréguier coast, this rumbling becomes a cannon blast.

4. The Sun and Health

Despite its celestial grandeur, the Sun is not the dominant star in popular beliefs: it is often the Moon, its mythical companion, that attracts attention and superstition. “People attribute far less influence to the Sun than to his wife, the Moon.”

In Upper Brittany, a curious belief holds that if the Sun enters someone’s mouth, it gives them… a fever. But conversely, the first rays of dawn are considered beneficial. They are even thought to possess healing virtues: the priest Jean-Baptiste Thiers, in his Treatise on Superstitions (1679), recommends a singular practice: “Standing naked before the rising sun, while reciting the Pater and Ave prayers several times, would cure fevers.” This morning ritual thus blends the natural power of the Sun with religious belief, a striking testimony to the spiritual way elements were once perceived.

5. Ceremonies Related to the Sun

Many folk healing practices were performed even before the Sun rose. This is particularly true for ritual ablutions: “Ablutions performed by the sick at the water’s edge are especially effective before sunrise, as with many magical ceremonies.” In several regions, the time just before dawn is seen as a temporal gap favorable to magical action: purification, healing, and prayers are believed to possess heightened power at this hour.

In Upper Brittany, certain processions to request rain also took place before dawn. The idea was to act before the Sun appeared, a symbol of drying, in order to implore water more effectively.

Sometimes, people even went against the current: when a pilgrim visited, by proxy, the sanctuary of Saint-Yves of Truth (Tréguier region), she had to walk three times around the chapel against the direction of the Sun. This ritual was part of a pilgrimage of hatred, with obscure symbolism, situated between divine justice and moral exorcism.

In certain beliefs, the Sun is the guarantor of a sacred domestic task. Thus, in several French provinces, it is said that Saturdays are always sunny for a very particular reason: In Picardy, “a ray of Sun is always guaranteed on Saturday, because the Virgin Mary needs to dry the Sunday shirt of the baby Jesus.” In Upper Brittany, it is even specified that this ray is meant to “dry her laundry”. This connection between light, purity, and divine motherhood anchors the solar cycle in everyday sacred life, between Christian cosmology and rural traditions.

6. Omens Drawn from the Sun

In some regions, sunlight plays a strong symbolic role during religious weddings. In Walloon Belgium, people watch for a sunbeam entering the church: “A ray of sunlight that sweeps across the church during the ceremony is seen as a sign of happiness.” Conversely, in Luxembourg, a sky darkening at the moment of the blessing is a sinister sign: “If the sun stops shining while the priest blesses the couple, the omen is considered bad.”

In the Liège region, attention is paid to sunbeams striking young people directly: if the Sun shines in the eye of a young girl or boy, it is a sign that the marriage will not take place that year; if a sunbeam strikes a young girl directly, her marriage will be delayed by a year. These meteorological details thus become markers of romantic destiny, often taken very seriously.

By the mid-15th century, a popular wisdom book, l’Évangile des Quenouilles, mentions several warnings related to the Sun. These medieval beliefs, tinged with superstition, reveal the fear of solar wrath:

7. Respect for the Sun

From the beginnings of Christianity, some believers continued to worship the stars, despite the clergy’s prohibitions. Saint Eligius, a 7th-century French bishop (588–660), expressed his outrage in one of his sermons: “Let no one call their master the Sun or the Moon, nor swear by them.” This rejection reflects the Church’s intent to break with the old solar cults inherited from Gallo-Roman paganism.

Yet, in the 15th century, these beliefs were still very present in popular culture, despite ecclesiastical efforts: in the famous Farce of Master Pierre Pathelin, a cloth merchant exclaims: “By the holy Sun that reigns!” (a distorted form of “règne”).

In Nogent-le-Rotrou, a court witness — Filleul Pétigny (identity unknown) — reported having heard a man swear: “I swear by the Sun.” These examples reflect a syncretism between Christian faith and ancient practices, still alive at the end of the Middle Ages.

The popular work L’Évangile des Quenouilles, a compilation of medieval female beliefs, explicitly mentions a benevolent attitude toward the stars: “He who often blesses the Sun, the Moon, and the stars will have his goods doubled.” Here, the stars are seen as sources of prosperity, rather than mere celestial objects without power.

In certain regions such as the Bourbonnais, ancient beliefs even intertwine the Sun with magical-religious practices. To break a spell, one must: “Kneel facing the rising Sun and recite a conjuration while staring at it.” The morning Sun is then seen as a purifying power, capable of undoing harmful charms.

8. Short Prayers Addressed to the Sun

In several regions, the sunrise is preceded by ritual words, sometimes spoken by children, shepherds, or the sick. These poetic formulas often have an affectionate or pleading tone: On the island of Balz:

“Little Sun of the Good Lord,

Rise up in the world,

Put on your little purple hat,

Put your little hat on your head

Before you become a captain.”

A childlike, almost magical language, meant to encourage the star to appear. In the southern Finistère:

“Come then, little blessed Sun,

Come see me,

I will give you a pot filled

With flowered butter.”

Here, one makes an imaginary offering, in the manner of a symbolic barter.

In the South of France, several prayers in Occitan are intended to ward off cold and death, and call upon the Sun to save the weakest:

« Soulèu, souleciel !

Levo-te

Per ti pàuris enfantet

Que nen moron de la fre. »

Translation: “Sun, little sky! Rise for these poor little children who are dying of cold.”

Another prayer:

« Sourelhet ! sourelhet, moun fraire,

Que lou bon Diu t’esclaire ! »

"- Petit Soleil ! petit frère,

Que le bon Dieu t'illumine !"

(“Little Sun, little brother,

“May the Good Lord enlighten you!”)

These invocations show a form of cosmic brotherhood between humans and the star.

In the heaths of Gascony, shepherds sing to symbolically warm children and animals frozen with cold:

« Arrâjo, arrâjo, souréillot,

Pastourét dé su la lâno,

Mort dé hâmi, mort dé fréd :

La hâmi qué passéra,

Mais lou fréd nou pouyra pas. »

French:

« Rayonne, rayonne, petit soleil,

Sur le petit berger de la lande,

Mort de faim, mort de froid :

La faim passera,

Mais le froid ne passera pas. »

Translation:

"Shine, shine, little Sun,

On the little shepherd of the heath,

Dying of hunger, dying of cold:

The hunger will pass,

But the cold will not."

Traduction : « Rayonne, rayonne, petit soleil, sur le petit berger de la lande, mort de faim, mort de froid : la faim passera, mais le froid ne passera pas. »

In the Jura, when the day drags on:

“Soureillo, pull down the cords

So the little shepherds may come home,

Who have nothing left in their little pouches.”

When the sky is overcast and the Sun remains hidden, the herdsmen of Upper Brittany recite a poetic incantation:

« Little sun, awaken yourself

Before the good Lord and before me,

Before the daughter of the king,

Who is more beautiful than I… »

A rhythmic attempt at persuasion, blending Christian faith with popular poetry.

Some health conjurations call upon the power of the Sun and the Moon. In Bourbonnais, a formula against skin diseases said:

“Canker, by the sun and by the moon, get out of here.”

But not all practices are peaceful: in Lower Brittany, a fierce imprecation curses all the stars:

« One hundred thousand curses I give you,

The curse of the Sun,

The curse of the Moon

And of the stars! »

9. Marvelous Aspects of the Sun

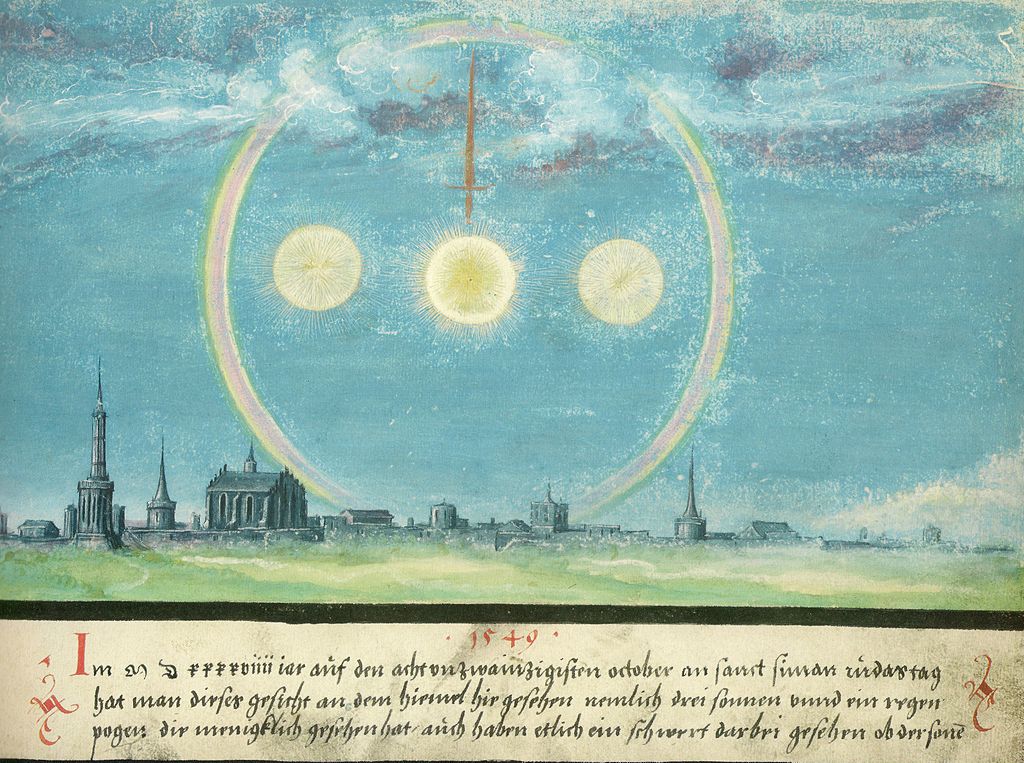

A still-lively belief in Franche-Comté recounts: “Anyone who, on Trinity Sunday — the first Sunday after Pentecost — before dawn, having taken communion and on an empty stomach, climbs Mont Poupet or La Dôle, will see… three suns rise.” This phenomenon, resembling an apparition, is also found in other regions: in the Vosges, it was enough to stand on a high point on the morning of Saint John’s Day. In Normandy, it is the elders who speak of it, and in Lower Maine, people enjoy mystifying by saying that on Saint John’s Day, “three suns fight, and the winner will shine for the whole year.”

This mysterious apparition is in fact a parhelion, an atmospheric phenomenon caused by the refraction of sunlight through ice crystals suspended in the atmosphere (often at high altitude in cirrus clouds). Two bright “mock suns” are observed on each side of the real sun, often at the same height on the horizon. Together, they can give the illusion of three suns side by side.

The struggle between the celestial bodies is another widespread motif: in Maine, the battle between Sun and Moon is said to take place at 3 a.m. on Saint John’s Day; in Poitou, it is said that by looking into a bucket of water on Easter morning, one can see the two bodies “fighting or dancing.”

Often, it is the Sun alone that is seen as dancing, a sign of celebration and renewal: in Creuse and the Limousin, this “dancing sun” is a joyful image. In the past, in the Norman Bocage, people would climb the hills to see the “three suns dancing.”

In Sorèze, villagers waited for the sunrise at the Mandre fountain, holding blackened glasses, to witness the solar dance in honor of Saint John. In the Messin region, on Easter morning, the Sun dances among the colorful robes of angels in the sky.

In Murat, it is said that on Saint John’s morning, the Sun rises black, “like a cauldron.” In Auvergne, on All Souls’ Day (November 2), the dawn does not appear in the West, a mysterious belief that defies the natural order. In the Albret, it is said that on the last day of the world, the Sun will rise in the west, climb until ten o’clock before falling, consuming the Earth.

About a century ago, in the mountainous regions of Provence, traces of a Sun cult were still observed. Numerous ceremonies took place at the summer solstice, often marked by sacred fires. These traditions are seen by several mythologists as the survival of ancient solar cults, bearing witness to a long cosmic memory.

10. Festivals on Midsummer’s Eve (St. John's day) or at the Return of the Sun

Leave a Reply