Forests in Fairy Tales: What Are Their Place and Role in Stories?

1. Ogres and Cyclopes

In French folk tales, forests are one of the favored settings for marvelous, unsettling, or tragic adventures. Under the “cover” of the trees unfold numerous stories featuring fearsome beings — often man-eaters — who prowl in the shadow of the woods.

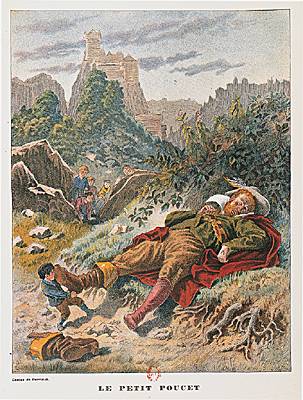

Like the famous Hop-o’-My-Thumb, many rustic heroes find themselves confronted with the fierce hunger of ogres, fond of fresh flesh. This theme appears, for example, in Lorraine around the mid-18th century, in the Essay on the Dialect of the Ban de la Roche (Oberlin, Strasbourg, 1775).

Ce conte en patois, repris plus tard par Charles Deulin dans Les Contes de ma Mère l’Oye avant Perrault, suscite l’intérêt des linguistes et des folkloristes. Sa présence dans plusieurs régions atteste d’une diffusion ancienne — même si beaucoup de versions n’ont pas été collectées ailleurs qu’en Upper Brittany, faute d’avoir été jugées suffisamment distinctes des contes de Charles Perrault.

In Ille-et-Vilaine and the Côtes-d’Armor, traditional ogres are joined by the Sarrasins, whose local name is synonymous with ogre. This assimilation reveals an ancient imagination in which the feared foreigner, a former enemy of France during their invasions of the country in the 8th century, is conflated with the figure of the man-eating giant.

In Lower Brittany, a tale mentions three giants and six giantesses, all greedy for human flesh, living in the heart of the forest. Their enormous appetite serves as the dramatic driving force in adventures where cunning often prevails over strength.

The forest also shelters giants with a distinctive appearance. The Golden-Beard Giant, a notable figure of Picardy, has an imposing palace hidden deep within the woodland.

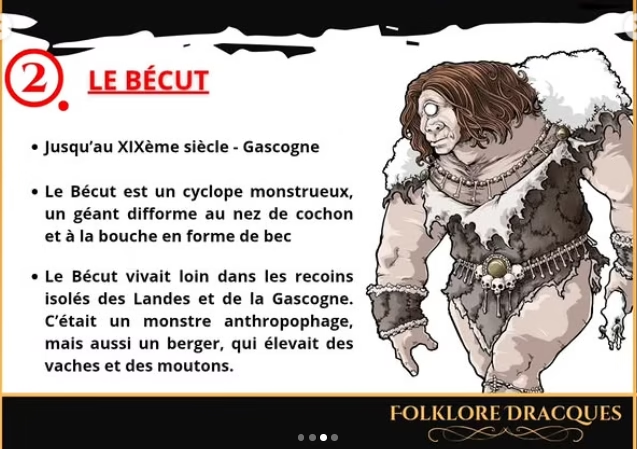

Even more terrifying, the cyclopean giant, with a single eye in the middle of its forehead, appears in a tale from the Côtes-d’Armor. In this local version, a young man manages to shoot out its eye, thus triumphing over the monstrous creature like Odysseus against the Homeric Cyclops.

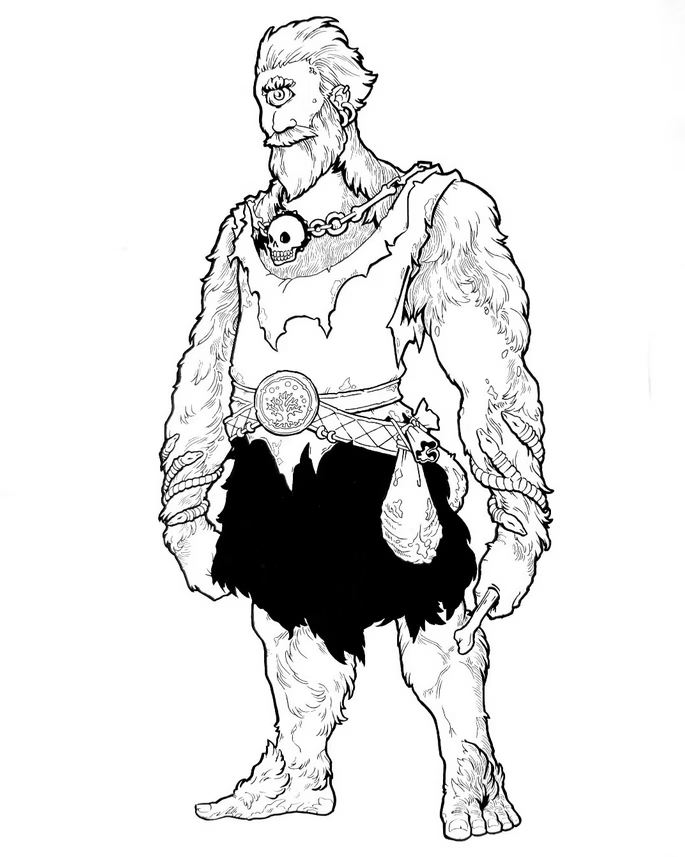

In the tales of the Basque Country, the Tartaro — sometimes called Tartare — appears as a hairy, enormous giant with a single eye in the middle of its forehead. It abducts careless children or lost travelers who come seeking shelter… before devouring them. However, some victims manage to pierce its eye, using strategies reminiscent of the clever Odysseus facing the Cyclops in the Odyssey. This reflects a universal mythological echo.

Another Basque creature, the Basa-Jaun — literally “wild lord” — shares a similar appearance and adventures. In one of the tales, a Basa-Jaun abducts a young girl and carries her off to his castle hidden in the middle of the forest.

In an Alsatian version of Hop-o’-My-Thumb, an old witch living in the woods lures children into a little dough house, whose roof is covered… with omelets. This tempting structure serves as a trap for the unwary, whom the witch captures to eat. This motif strongly recalls the Germanic tradition of edible houses, popularized by the tale of Hansel and Gretel.

The vast forests also serve as the favored setting for the most spectacular monsters of folklore. Storytellers notably place there:

2. Similar to Hop-o’-My-Thumb

The motif of children abandoned in the heart of the forest is one of the oldest and most widespread in European folklore. In France, many versions directly recall the theme of Hop-o’-My-Thumb, while adding regional and storyteller-specific nuances.

In many tales similar to that of Hop-o’-My-Thumb, parents lead their children into the woods to deliberately abandon them. Sometimes, it is not a boy but a young girl who is left: either because she is more beautiful than her sister, or because her jealous stepmother wants to get rid of her. There is also a motif borrowed from the legend of Genevieve of Brabant: men tasked with killing a girl or woman and bringing back her heart to the sender ultimately substitute an animal’s heart, thus sparing their victim. A theme blending betrayal, cunning, and ambiguous morality.

Many of these characters, wandering in the depths of the woods, climb a tree to try to catch a glimpse of a sign, an anchor of hope. Often, they spot a distant light through the branches. This nocturnal beacon then leads them — like the Pearl and her brothers, as well as several other “Hop-o’-My-Thumb similars” — to an ogre’s house, where a new series of trials begins.

But not all share the same misfortune: some tales choose an outcome more magical than terrifying.

3. The king lost while hunting

A recurring motif in French tales features a king lost in the forest, a situation made famous by Collé’s play, La Partie de chasse de Henri IV. This theme has been retold in various regions, sometimes attributed to different monarchs. These stories generally involve kings very devoted to their hunts, known for imposing severe punishments on those who dare to break their rules.

In Upper Brittany, le roi surnommé Petite Baguette, ou roi Grand Nez, reçoit l’hospitalité d’un sabotier. Celui-ci lui sert un lièvre et le met en garde : « ne pas le dénoncer ». L’épisode souligne la discrétion et la loyauté des gens simples face à l’autorité.

In Gascony, a charcoal burner offers Henry IV a wild boar’s head, also advising him not to reveal anything to King Big Nose. The tale highlights the cleverness and kindness of the locals in the face of royal authority.

In Ariège, the encounter is less dramatic but equally significant. The king, hungry, receives breakfast from a charcoal burner who tells him about the miseries of the people, particularly the heavy burden of taxes. This variant emphasizes the monarch’s closeness to the people’s suffering, a moral and social element of the tales.

4. Dangerous Castles

Adventurers sometimes find themselves facing isolated castles, nestled in the heart of dense forests. Although they appear intact and in good condition, these castles often seem uninhabited and conceal unsuspected dangers.

At certain hours, a dwarf of prodigious strength may appear, and visitors have great difficulty resisting him. Other castles, whose tables seem set for an invisible meal, are haunted at midnight by devils, guardians of a transformed princess. These tales create an atmosphere of suspense and danger that characterizes forests in folklore.

Some castles are visible from afar by a dazzling light in the midst of the trees. Legends say that no visitor has ever returned, because an old woman guarding it turns the unwary into statues. In a Basque version, the castle is even more mysterious: it appears only at night, and when day breaks, it vanishes to reveal a cave where a dragon dwells, the ultimate symbol of danger and trial.

5. Forest-Related Trials Imposed on Heroes

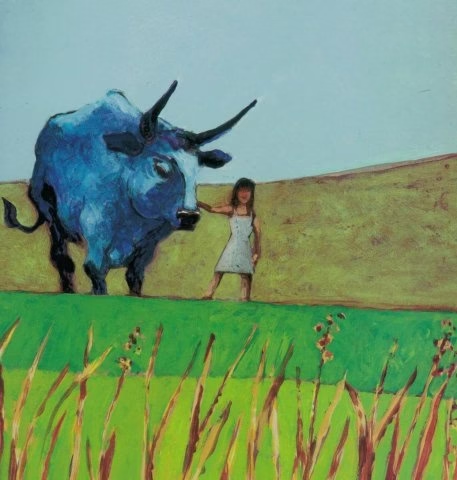

The forest is not just a place of passage, but a true testing ground for heroes. It challenges their courage, ingenuity, and ability to follow often mysterious instructions. In the eponymous tale, the Blue Bull (pp. 15–22) carries a young anonymous girl persecuted by her stepmother. Before crossing three forests, he warns her:

These leaves produce a particular sound when touched, and this sound is capable of awakening ferocious or venomous beasts. Thus, following instructions becomes vital for surviving the forest. When the hero tries to escape from his host, he often rides a talking horse, which advises him during his flight. Along the way, he drops an object from the stable — a sponge or a curry comb — and at the spot where it falls, a great forest immediately springs up.

Heroes and trials in legendary forests: Blue Bull, magical leaves, and forests rising from magic. Discover the fantastic French tales. »

6. Hermits and Thieves

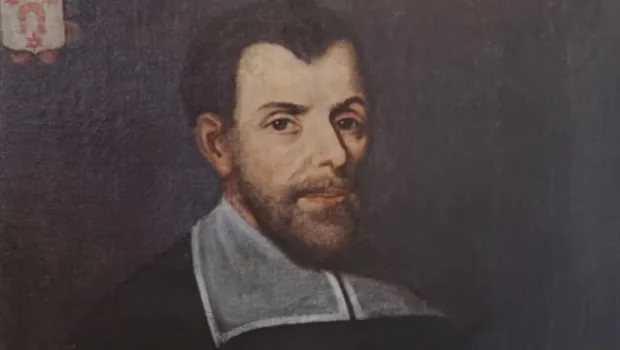

Pierre Le Gouvello, Lord of Kériolet.

In Lower Brittany, the forest serves as a refuge for hermits, who live in primitive huts, leading a life of penance. Despite their austere appearance, these hermits are often endowed with great power, and some exhibit supernatural traits. This tradition is also found in Berry, indicating a fairly wide diffusion of this motif.

The memory of thieves who inhabited the most remote woods has been preserved in folklore. Although these tales are less magical than those featuring fantastic creatures, they illustrate the fear and danger within forests. Just like the Corsican maquis, certain French heathlands served as refuges for outlaws and brigands. These isolated and hard-to-reach areas provided ideal shelter for those fleeing justice. While popular memory has preserved few detailed stories of their exploits, a legend persists in the vast Lanvaux heath in Morbihan, famous in the early 17th century for harboring notorious thieves. According to this still-living tradition, Pierre de Kériolet, renowned for his crimes before turning to penance and being sanctified, would mingle with the brigands alongside his friend Bonimichel.

Thieves often reside in an abandoned house or castle, and may slaughter those who come seeking hospitality, unless the visitors manage to escape through cunning or intelligence. However, there are exceptions: some thieves show compassion for the poor, introducing a moral contrast into popular tradition.

Many tales speak of enchanted beings, often transformed into animals, who undergo their penance in the forests. Among them:

7. Supernatural Beings