Creatures of the Mountains: Genies, Spirits, Demons, and Wyverns

1. Malevolent Spirits of the Peaks

In the French and Swiss mountains, certain supernatural beings are known to be malevolent. These spirits, secret inhabitants of the peaks, do not like people telling stories about their deeds. Local guides therefore remain very discreet when questioned, out of fear of irritating them with indiscretions.

These figures are often jealous of their domain and react violently when humans venture into it. In the village of Lescun, residents watch with suspicion any outsider who climbs Mount Aurie. According to tradition, this peak is the dwelling of Yona Gorri, « the being clothed in fire”, capable of unleashing devastating thunderstorms across the plain to take revenge for any intrusion.

At the summit of Pic d’Anie lives a lonely and melancholy spirit. Its height surpasses that of the tallest fir tree, and it tends a secret garden where plants with supernatural powers grow. Their sap can multiply human strength tenfold and drive back the demons guarding hidden treasures. But anyone who dared to pick these plants or visit the spirit’s dwelling would immediately unleash terrifying storms. These tales remind us that the mountain is not only a place of beauty, but also a sacred and dangerous realm, where natural and supernatural forces intertwine.

In the Aspe Valley and in several regions of the Vaud Alps, people still fear the influence of the mountain spirits. These beings have the power to form and disperse storms, to protect springs and fountains, to guard gold mines and crystal caverns, and to hunt noisily through the precipices they inhabit.

A famous example collected by Abbot Philippe-Sirice Bridel tells the story of a young shepherd from the Ormonts, passionate about hunting chamois despite his parents’ prohibitions. One evening, caught in a violent storm on the precipices of the Alps, he found himself trapped by snow and cold. Suddenly, the mountain spirit appeared in a whirlwind and shouted at him in a threatening voice:

“Reckless one! Who allowed you to come and kill the herds that belong to me? I will not hunt your father’s cows: why do you come to hunt my chamois? I am willing to forgive you this time; but do not return.”

After this warning, the storm subsided, and the young shepherd was able to return to his chalet, learning to respect the rules of the invisible realm of the peaks.

2. Tempest Spirits

In the Pyrénées, local legends tell of a wild man, dwelling in the abysses of the mountains and forests. His body is covered with long silky hair, he carries a staff, and he runs faster than the chamois. He feeds on roots and, it is said, steals the shepherds’ milk, who nickname him Basajaun, or Bassa Jaon. This mysterious figure also serves as a storm warning. As bad weather approaches, he shouts through the mountains to warn the shepherds: “Arretiret, bacquié.”

In the Landes, peasants claim that the Black Man appears on the Pyrenean peaks when hail and storms threaten the crops. The hailstones seem to literally fall from his hand. This role of tempest spirit (storm summoner) is often attributed to an infernal genius, notably on Pic du Nethou, where he conjures hurricanes, lightning, and torrents of rain to protect his domain.

Some mountains in the region are reputed to be inaccessible to mortals. In the land of Barèges, at the end of the 18th century, it was said that only one man had reached the summit of Monte Perdido, but thanks to Satan, who guided him along seventeen steps before hurling him from the peak, stealing his soul in the process. These stories highlight how the Pyrenees were perceived as sacred and formidable territories, where nature and the supernatural intertwine.

3. Spirits of Dangerous Passages

The narrow and perilous passages of the mountains, where a single misstep can plunge a traveler into deep crevices, have long been associated with malevolent spirits. According to the beliefs of the Dauphiné mountaineers, each abyss harbors invisible entities that fix their gaze on passersby to fascinate them and draw them into their damp dwellings. These beings exploit human fear and curiosity to punish the reckless.

In the Pyrénées, every dangerous rock and chasm seems to be under the protection of a malevolent fairy known as the Fairy of Vertigo. With their fiery gazes and wild beauty, these sirens enchant reckless travelers. With hearts gripped by fear, visitors sense the imminent misfortune, but it is too late: their recklessness can cost them their lives, while the laugh of satanic joy mingles with the whispers of the wind.

In the department of Ain, female spirits called the Pierettes haunt the gorge of Hôpitaux, dominated by tall rocks. These entities roll stones onto travelers who venture recklessly onto their lands, reminding that the mountain is not only a place of beauty, but also a space where danger and the supernatural coexist.

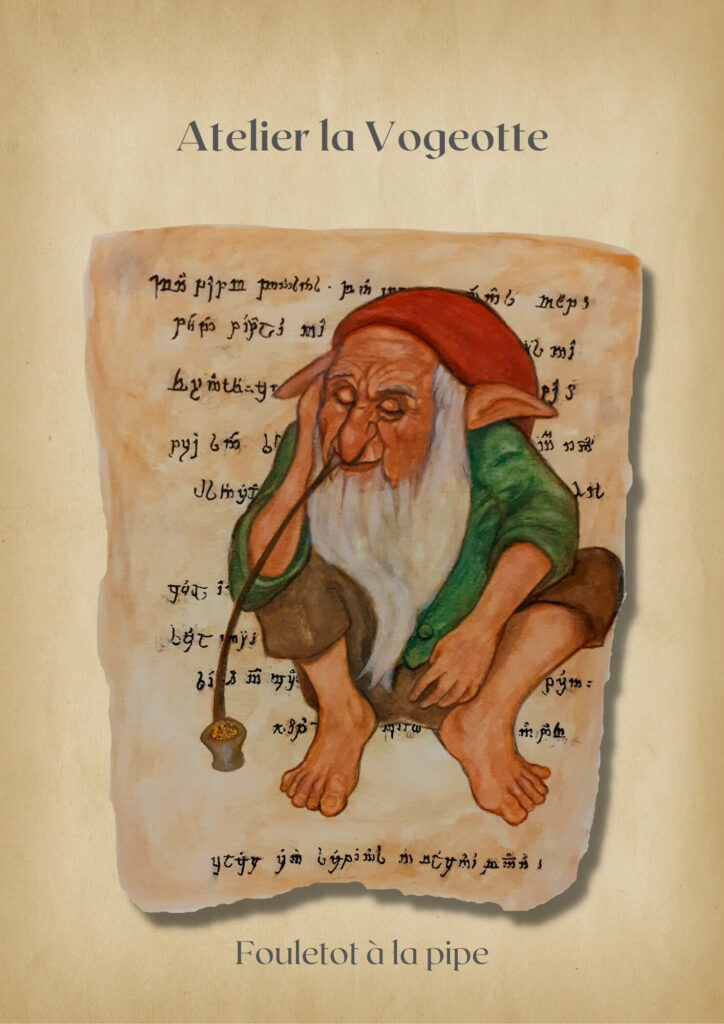

4. Mischievous and Touchy Goblins

In the past, the mountain goblins were numerous and, although sometimes mischievous, rarely malevolent. Stories often portray them as benevolent toward the inhabitants of chalets and pastures, yet very touchy and quick to take revenge on those who disrespected them. In the Alps and the Pyrénées, the “servants” were friendly household spirits who entered homes in the absence of the mountaineers to perform a multitude of small tasks.

In Alsace, around the 14th century, it was said that after the last shepherd left Mount Kerbholz, these dwarfs, accompanied by their livestock and their tools for butter and cheese, would settle in the empty chalets and work there day and night. In winter, they would descend into the valleys to quietly leave butter and cheese of the highest quality in the huts of the poor.

In the Vaud Alps, the goblins protected the chalets and helped shepherds drive the herds. They guided the cows along the steep paths while reciting magical formulas such as:

“Pommette, Balette! Go where I go, and you will not fall from the rocks.”

In the Jura Alps, the fouletots would sometimes lure a cow deep into the woods while the shepherdess slept, then return it well-fed with swollen udders, as a reward for the patience and respect shown to them. In return, the servants demanded a small traditional offering, often the first portion of the best cream from the evening or morning milking.

The goblins did not tolerate neglect: one example at Lac Lioson shows that a young shepherd who forgot to leave the servant’s share saw the herd crushed at the bottom of an abyss after a nocturnal storm, accompanied by a threatening voice shouting at him:

“Pierre, rise, rise to flay!”

Like the fairies, the goblins hated filth. They permanently abandoned certain regions when residents soiled the milk left for them.

5. Malevolent Goblins

In the Vaud Alps, some goblins manifested at night in the form of small lights, marking their discreet yet visible passage to human eyes. At Rubli, the goblins called gommes watched over an underground mine. They were sometimes seen in the form of meteors when visiting their companions on other peaks.

Not all goblins were benevolent. On Mount Coucu, a will-o’-the-wisp would roll enormous rocks onto the paths of passersby, creating a noise like the collapse of an old wall. In the Pyrénées, the spirit targeted the horses in the pastures: it would climb onto their backs, make them leap across the rocks, and wound them with an invisible spear, spreading fear among shepherds and travelers.

6. Giants

According to tradition, giants helped shape certain secondary mountains and loved to stroll there. During the Golden Age of the Alps, Gargantua would stride across fields and forests with enormous steps. When he sat on a chain of hills separating two valleys, one leg would hang on one side and the other descend on the opposite side. In Savoie, he rested on the peaks as if they were a stool the size of his body, played with the fir trees like light straws, and dipped his feet in the lakes. Children in the valleys still imagine the giant of the Servance balloon sitting in front of Mount Them as if before a served table.

Some legends tell that man-eating giants once inhabited the mountains of the Doubs. One day, an exorcist priest dropped a rock so heavy in front of the cave of one of these giants that he remained trapped there for eternity. In Alsace, a huge giant named Roege resided on the hill of Nollen.

The last giant of Vaud tradition, called Pâtho, lived in a cave and only emerged at night or in foggy weather. Shepherds said that his piercing cries made the mountaineers shiver, and that sometimes he carried a lantern to move around.

Some mountains even served as tombs for giants. In Alsace, the giant said to have formed the Munster Valley is buried beneath the majestic peak of Hohenack, called by the mountaineers the giant’s tomb. It is said that, in the silence of the night, he sometimes awakens and his movements produce horrible groans, reminding all of the presence of the ancient colossi.

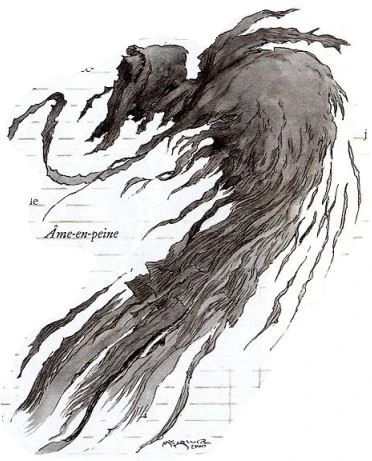

7. Revenants

Some mountains remain haunted by revenants, souls that have not found rest after their earthly life. The drowned, for example, cannot rest in peace if they have not been buried in holy ground, while others are condemned to perform penances where they committed their misdeeds.

On clear nights, it is sometimes possible to see three flames flickering above a crevasse, where three guides were buried under two hundred feet of snow. These flames represent their souls deprived of a Christian burial. As Alexandre Dumas notes in Impressions de Voyages en Suisse, some Rhône glaciers even display areas of red snow, a mysterious sign of invisible presences.

A passage once heavily traveled by Italian muleteers carrying wine tells a legend of punishment. Abusing the trust of the locals, these men drank the wine they were transporting and replaced the deficit with snow and water. As a result, their shadows must wander over the Névé until a compassionate soul ends their torment. To appease them, one simply needs to make the sign of the cross and sprinkle red wine on the red snow, thus performing a ritual of redemption and freeing these tormented souls from the icy purgatory.

8. Posthumous Penances of Thieves and Old Maids

In the Vaud Alps, some revenants are subjected to strange posthumous penances. Goatherds who neglected the care of their flocks would endlessly bleat their calling cry until dawn: “Ta bédjet, tiens chèvre!” As for shepherds who mistreated or threw their animals into the precipices, they return in spirit form until the value of the animal is restored, thus fulfilling their penance.

In French-speaking Switzerland, a shepherd who had stolen salt while tending his flocks would return each winter to the chalet where he had committed his theft. Condemned to grind and regrind endlessly the stolen amount of salt, he repeated this task tirelessly until his wrongdoing was rectified. A legend from Nendaz, a valley opposite Sion, tells of a woodcutter who encountered such a revenant in the attic of Siviez. The dead man, dressed in black rags and smelling of sour milk, asked the living man to ensure that his descendants returned the twenty-five measures of stolen salt, then vanished like smoke into the valley.

In Lower Brittany, the souls of Purgatory manifested through plaintive cries on the mountains. Legends tell that old maids, those who had refused marriage, are condemned after death to perform arduous tasks. On the mounds of Brandefer above Plancoët (Côtes-d’Armor), they must let their nails grow to scratch the earth, under the watchful eye of Saint Verdagne.

In French-speaking Switzerland, girls deemed too difficult to marry are condemned to endlessly climb the slope of a gigantic, constantly crumbling sand scree, visible in Muraz on the left bank of the Rhône. These stories reflect popular beliefs related to posthumous punishments and rites of moral justice in mountainous regions.

9. Restless Souls

On the summit of Boelchen, near Sulz, the souls of surveyors who deceived people in their work return to atone for their sins. Their punishment? Perpetually measuring the mountain, an endless torment that haunts this high place.

In the past, the muleteers of the Loue Valley witnessed frightening phenomena when following the steep path from Mouthier to the summit after sunset. They heard lugubrious cries and saw hideous and formidable specters appear in the air. The damned and suicides sometimes descended near Aven or Ardon, emitting dreadful groans. Their bodies, worn from centuries of wandering over the rocks, bore the marks of their long penances: arms worn down to the elbows or shoulders, and eternal fatigue.

In Alsace, the hill of Hochfeld is known for its mischievous ghosts that lead visitors astray. Even locals familiar with the terrain sometimes get lost for hours in broad daylight, victims of the spirits haunting the area. The revenant surveyors of Boelchen could also mislead those attempting the ascent, adding an aura of mystery and danger to the mountains.

Between the peaks of the chalets of Saint-Pierre and Sarre, in the Aosta Valley, lies the Lake of the Dead. Tradition holds that anyone daring to walk three times around its shores while saying: “Lake of the Dead, where are the dead?” would see a vengeful shadow rise and drag them to the bottom of the water, shouting: “Come see who my dead are!”. According to legend, the lake takes its name from the corpses of fighters who fell during a battle between the living and the dead.

10. Stone Piles on the Mountains

In many mountainous regions, from the Dauphiné to the Swiss and Savoyard Alps, an ancient custom held that travelers would throw a stone at the site where an accident had caused a person’s death. Over time, these piles of stones grew considerable and formed a kind of galgal, a cairn symbolic of memory and respect. In the past, this practice was almost sacred. For example, the chief of the shepherds of the Ariège mountains would swear to place a stone on every victim of the storm. Even in Lower Brittany, where the mountains are modest, this custom persisted, as the following legend shows.

Between the two peaks of Ménez-Hom lies a cairn called Ar Bern Mein, literally “the pile of stones.” Its origin dates back to a Breton king, King Marc’h, powerful but hot-tempered. Devout to Saint Mary of Ménez-Hom, he had the chapel built, which is still visible today. At his death, God, moved by the Virgin’s prayers, condemned his soul to remain in his grave until it was tall enough for him to see the chapel’s bell tower.

One day, a beggar saw near his grave a beautiful lady carrying a heavy object in her dress. She asked him to place a stone where she would put hers. The beggar obeyed and received a gold louis as a reward, with the instruction to pass on this gesture to all travelers. Since then, the pile of stones has grown year by year, each passerby adding their stone in tribute and in memory of King Marc’h and the tradition.

11. Exorcisms of demonic Spirits

Mountains have long been considered places inhabited by infernal spirits, responsible for terrible landslides, sudden storms, or unexplained phenomena. To protect themselves from these malevolent forces, locals sometimes performed exorcisms at the sites where these beings were believed to dwell.

In the Valais, it was said that demons made their moans heard and glowed with sinister little lanterns at night, notably before the disasters of 1714 and 1749. Before these landslides, dull noises and underground explosions were heard in the depths of the Diablerets, signaling the fury of the malevolent spirits.

A Jesuit priest from Sion warned the Valais shepherds: the area was the suburb of the devil and the damned, where two factions of demons clashed—one to push the mountain toward the Valais, the other toward the Bernese. This struggle caused uproars, cracklings, and underground battles, heralding imminent disaster. In 1714, the priest of Fully took action: he positioned himself on the Ardon Bridge and exorcised the demons to protect the village from the wrath of the malevolent spirits.

12. Gatherings on the High Places of Demons and Witches

Depuis longtemps, les montagnes sont perçues comme le théâtre d’actions surnaturelles. Les orages qui éclatent sur le Mont-Blanc étaient autrefois attribués à la colère des esprits infernaux, envoyés par la justice divine pour punir les habitants pour leurs mœurs relâchées. Certaines années, les glaciers semblaient avancer jusqu’aux habitations, envahissant les terres cultivées, obligeant les villageois à recourir aux prières et exorcismes de l’Église.

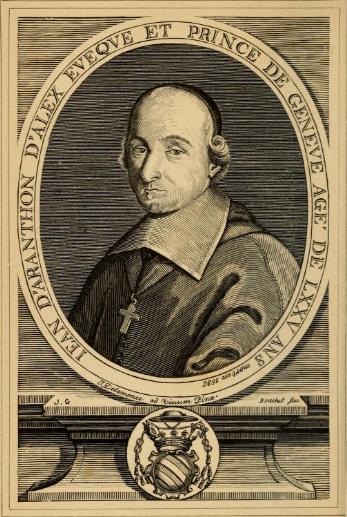

Vers la fin du XVIIe siècle, Jean d’Aranthon, évêque de Genève, s’avança jusqu’au pied des glaciers de Chamonix pour les exorciser. Depuis, les mauvais esprits ne seraient plus réapparus. Mais la croyance populaire attribuait aussi ce pouvoir aux habitants eux-mêmes : en 1719, des paysans du canton de Berne demandèrent au bailli d’Interlachen l’autorisation de faire reculer les glaces grâce à un sortilège, pratique qu’ils auraient appliquée secrètement.

Certains sommets servaient de rendez-vous aux tempestaires, sorciers et démons. Par exemple, le Mont Anie dans les Pyrénées était considéré comme un arsenal d’orages, d’où sorciers et démons lançaient grêle et tempêtes sur les villages. Dans le Béarn, un proverbe disait :

« At soum d’Anie, De brouixs, brouixes y demounsfurie »

Dans de nombreuses régions de France et d’Europe :

Outre les sabbats, d’autres apparitions nocturnes effrayaient les villageois :

Ces légendes témoignent de la peur et du respect que les populations anciennes avaient pour les hauts lieux montagneux, considérés comme des carrefours entre le monde des hommes et celui des esprits, démons et sorciers.

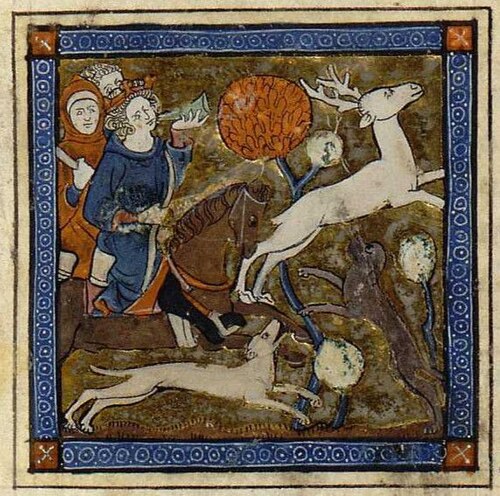

13. Chasses maudites

Certaines montagnes françaises sont réputées pour abriter des chasses maudites, des cavalcades spectrales qui traversent les sommets au galop.

In Lautenbach, par exemple, Hubi, the chasseur nocturne, franchit la montagne de Dornsyle à toute allure sur son cheval. Dans le Cantal, the Grand Veneur parcourt les vallées de Brejons and Malbo avec sa meute et sa suite infernale. Ces apparitions surviennent à des jours et heures inconnus, et celui qui oublie de se signer disparaît à jamais, sans laisser de traces.

In Lauragais, à Vieillevigne, on raconte qu’Arthur, le roi légendaire, chasse chaque année avec sa meute de chiens blancs pendant septembre ou octobre, à l’époque des vendanges. Sa course fantomatique commence aux coteaux d’Es Selves et s’achève sur le coteau d’Escoyolis. Selon la légende, il est condamné à chasser éternellement, punition pour avoir, comme ses semblables des forêts et des airs, quitté la messe au moment de l’élévation pour poursuivre un lièvre.

14. Animaux fantastiques

The montagnes françaises regorgent d’animaux réels, comme les ours, the chamois et les aigles, mais certaines légendes évoquent aussi des créatures fantastiques.

Autour d’Aulus, les habitants redoutaient le Lou’ mmâgré, the loup maigre, décrit comme un être malfaisant et colossal. Selon la tradition, il pouvait, en un instant, anéantir un troupeau entier, et les bergers récitaient des incantations pour protéger leurs animaux contre ce prédateur surnaturel.

Parfois, les légendes prennent un ton plus singulier et mystérieux. Avant la Révolution, la montagne du Mené aurait été le théâtre d’un combat extraordinaire entre chats, laissant plus de mille matous sur place. Une tradition de Givet in 1829 raconte qu’une assemblée de chats s’était rendue à la Tieune des Martias — le Mont des Marteaux — pour se battre, donnant lieu à un spectacle étrange et mémorable pour les habitants de la région.

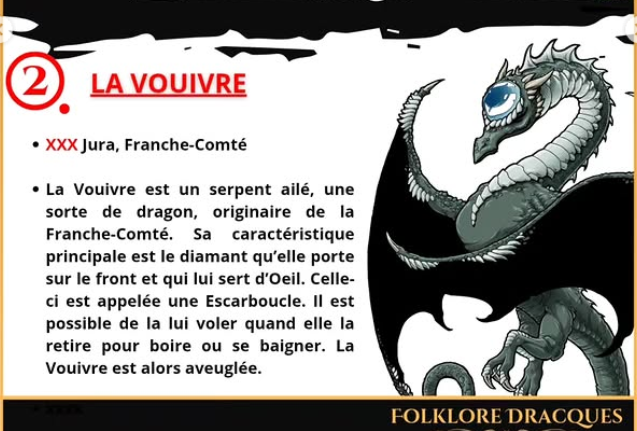

15. Vouivres