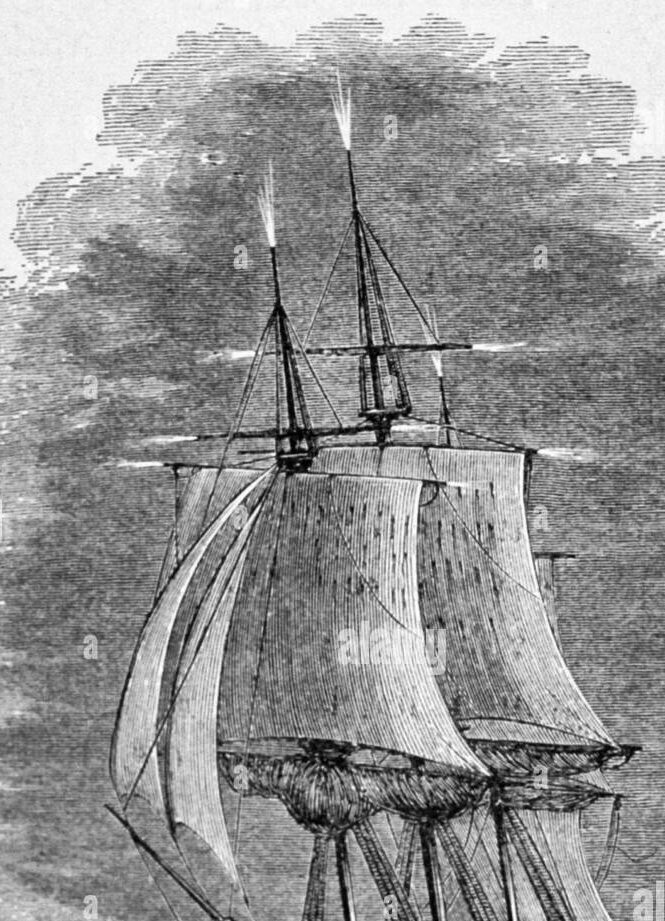

Legendary torrential storms: thunderstorm, rain, and St. Elmo’s fire

1. Names and origins

The St. Elmo’s Fire is a very real physical phenomenon. It appears as small flashes of plasma generated by specific atmospheric conditions. These glows generally appear at the tips of ship masts and on the wings of modern aircraft (see: couleur-science.eu)

In the days of traditional seafaring, it was known by various names: Wandering Fires, Little Flames, Furoles, the Ardent, or even Goualaouenn red (literally “wandering candle” in Breton).

Its glow also inspired more unsettling names, such as Devil’s Fire, linking it to infernal forces. But more often, it bears the names of protective saints:

It is nevertheless the name Saint Elmo (or its many dialectal variants) that became the most famous. It refers to Erasmus of Formia, a martyred bishop of the 4th century and protector of sailors. Over time, his memory became intertwined with the fears and hopes of seafarers.

Beyond its physical reality, St. Elmo’s Fire is also a bearer of legends.

Sailors from Saint-Malo tell that one day, Saint Elmo, shipwrecked in a helpless boat, was rescued by a compassionate captain. Refusing any reward, the saint promised in return to warn sailors of danger by sending them a fire at the critical moment. Since then, this glow appears as a storm approaches, like a sacred warning sign.

On the Brittany coasts, the fire is sometimes seen as a wandering soul, bound by blood to the one who sees it. It is said to implore prayers to ease its torment in the afterlife. In Brittany and Saintonge, these onboard fires are associated with drowned sailors, returning to haunt the ships where they once served.

Interpretations of St. Elmo’s Fire vary by region and era.

Sailors of the English Channel consider it a bad omen. On the coast of Tréguier, it foretells the loss of a loved one. In Finistère, a proverb says:

“The St. Elmo’s Fire on the sea is Death asking to be let in.”

But for others, seeing this fire during a storm is a promise of calm:

Result: good weather is imminent.

From the mischievous sorcerer glimpsed in the 16th century to lightning phenomena explained by science, St. Elmo’s Fire remains a powerful symbol of maritime traditions. It crystallizes ancestral fears, the hope of survival, and the sacred bond between humans and the sea.

2. The Thunderstorm: explaining the sound of thunder and lightning

In many regions of France and Belgium, thunder is perceived as a supernatural manifestation, sometimes diabolical, sometimes divine. In Franche-Comté, it is said that the Devil invented thunder. In Gironde, people address it in prayers: “Storm, be gone to the Devil!” For Walloon farmers, thunder expresses either the Devil’s mischief or God’s wrath. In Lower Brittany, it is said that the storm rumbles when the soul of a wicked person escapes from a hole dug by lightning, carried away by the wind.

The violence of the elements sometimes becomes divine justice: in Auvergne or Brittany, the death of a usurer or a cruel rich person is invariably accompanied by storms, heavy rains, or lightning. The fury of the skies only subsides once the corpse has left the house.

In the Walloon region, thunderstorms were believed to be caused by enormous stone balls rolling across the sky. When two of these balls collide, the impact produces lightning, and fragments fall to the ground: these are the famous thunderstones, sometimes found in fields. But these “celestial games” are not always frightening: they are often explained to children to reassure them, sometimes poetically, sometimes humorously.

In Wallonia, Upper Brittany, Limousin, or Bigorre, God plays skittles when it thunders. In Ille-et-Vilaine, it is Jesus Christ. In Burgundy, the angels. But in Le Perche, it is the Devil having fun.

In Morat, the site of Charles the Bold’s defeat, thunderstorms are caused by the souls of the Burgundians, playing in the skies. In Poitou, God is shaking walnuts; in Hainaut, he is carrying sheaves; in Normandy, he is moving his daughters’ trousseau; in Auvergne, the Devil is threshing his wheat in decas; in the Morvan, children believe that their grandfather is rattling clogs to choose them a pair.

Lightning also has its marvelous tales. In Wallonia, some say: “When it lights up, God is lighting his pipe.” But another, more mystical version claims: “When it thunders, the sky opens slightly, and the lightning is the light of paradise escaping.” It is even said that if someone dared to look through this celestial opening, they would see the kingdom of the blessed… but would be struck blind. Yet in Normandy, young fishermen dared to fix their gaze on the sky at the moment of lightning, convinced they could glimpse the figure of the Virgin in a corner of paradise.

The mystery of lightning remains so deep that it is said to have been deliberately hidden by God, even from His apostles. In Franche-Comté, it is said that when Jesus was teaching His disciples, one of them asked: “Master, what is thunder?” Saint Peter wanted to write down the answer, but Jesus stopped his hand and declared:

“Stop, Peter,

If man on earth

Knew what thunder is,

He would turn to ashes and dust.”

Another touching story comes from the Puy-de-Dôme: Saint John asked to see thunder. God refused, fearing that he would die of fright. Saint John insisted, claiming he had endured the worst torments. God relented… and immediately, John was dazzled, thrown to the ground. This is said to be the origin of epilepsy, or the “Saint John’s malady.” From that day on, God decided that every thunderclap would be preceded by a flash of lightning, to warn mankind.

3. Animism

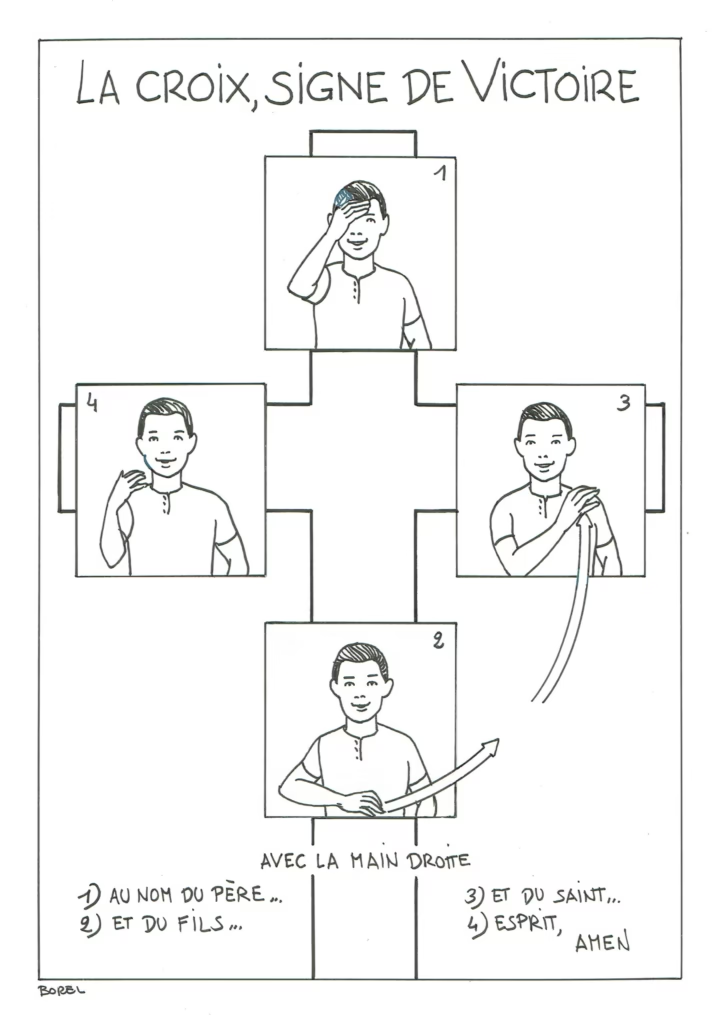

In several traditions, lightning plays a protective role: it signals thunder and allows humans to prepare or take shelter. In Albret, lightning is also seen as a benevolent warning from God. In Wallonia, this role is attributed to the Virgin Mary, who sends lightning to warn that the Devil is about to thunder. In Franche-Comté, it is said that when the Devil invented thunder, the first humans were seized with fear. Then good God said to them:

“Fear not, whenever he is about to thunder, I will warn you with a flash of lightning. Thus, by making the sign of the cross, you will be able to ward off this new evil.”

In several rural tales, meteors are endowed with speech, as if they were animated by their own will, capable of deliberating, getting angry, or showing mercy.

A touching story reported near Hyères illustrates this idea. Two young peasants had taken shelter from a storm under an old wall overgrown with a caramandrier—a plant believed to possess mysterious powers. They then heard a surreal exchange between the elements themselves:

L’éclair dit au tonnerre : « Tiens, brise encore ceci, casse encore cela. »

Le tonnerre répondit : « Voilà, c’est fait. »

L’éclair ajouta : « Tiens, tue les deux enfants. »

Et le tonnerre de répliquer : « Ce n’est pas possible, ne vois-tu pas qu’ils sont sous le caramandrier ? »

"Lightning said to thunder: “Here, break this again, smash that again.”

Thunder replied: “There, it’s done.”

Lightning added: “Now, kill the two children.”

And thunder retorted: “That’s not possible, don’t you see they are under the caramandrier?”

Here, the caramandrier plays the role of a protective tree, a vegetal sanctuary against celestial forces.

In Berry, another remarkable story recounts a dialogue between two storm clouds approaching the village of Thevet: as the storm threatens, the sacred bell, named Martin, is rung. The clouds, ready to unleash their fury, hesitate:

« Nous arrivons ! Avance ! Avance ! »

— « Pas possible ! Martin parle », répond la deuxième voix.

— « Eh bien, prends à gauche et écrase tout ! »

“We’re coming! Forward! Forward!”

— “Impossible! Martin is speaking,” replies the second voice.

— “Well then, turn left and crush everything!”

Immediately, the clouds bypass Thevet, sparing the parish of Saint Martin and pouring fire and hail over the neighboring villages. Not a single drop falls on the lands protected by the bell’s voice.

This story is not isolated. In many regions, ringing the bells during a storm is a deeply rooted tradition. It was believed that the sound vibrations would drive away storm clouds or break their destructive charge. In Saintonge, this practice still continues: the sacristan receives gifts in kind for “ringing the storm” as soon as the sky darkens.

4. The sun is shining despite the rain

In France, rain is rarely seen as a character. But in Upper Brittany, it has a name: Mother Banard, wife of the West Wind. In a local tale, the Mother of the Winds is also the mother of Rain and Frost. In the Côtes-d’Armor, the expression “la pouche est déliée” — used to describe a heavy shower — may trace back to an old belief: that of a mythical figure holding rain in a bag, much like Aeolus, the master of the winds.

The coincidence of rain and sun gives rise to animistic interpretations. The sunbeam is often depicted as a male character, while the rain, more discreetly, is a female figure. In Paris, it is said that good God waters His garden (Henry Carnoy, La Tradition, 1893). In Antiquity, it was claimed that Jupiter and Juno were quarreling when the phenomenon occurred. In Gascogne or Upper Brittany, it is said that the Devil and his wife are fighting. A song from Languedoc illustrates this scene rhythmically:

Plòu e fai sourel (Il pleut et il fait soleil),

Lou diable se bat ambe sa femna (Le diable se bat avec sa femme),

Zounzoun. Amai siegue garel (Cahin-caha, quoiqu’il soit boiteux),

Vai per l’agantà (Il va pour la saisir),

Ambe sas arpas ie fai antau : (Avec ses griffes, il fait ainsi)

Flic ! Flac !

Plòu e fai sourel (It rains and the sun shines),

Lou diable se bat ambe sa femna (The Devil is fighting with his wife),

Zounzoun. Amai siegue garel (Hobbling along, though he is lame),

Vai per l’agantà (He goes to grab her),

Ambe sas arpas ie fai antau : (With his claws, he does this)

Flic! Flac!

This staging, often mimed by adults to entertain children, reveals an imagination in which the elements of the sky become characters in a divine theater.

In the sayings, it is almost always the Devil who beats his wife, sometimes his daughter or his mother. In these cases, rain becomes tears, and the storm a celestial quarrel. Variants even mention the tools of punishment, often linked to rhymes. In Saintonge: with a cap. In the Norman Bocage: with a broom. In Hainaut, the Devil beats her in a basket; in the Ardennes, he punishes his daughter.

In Lower Normandy: with a hammer — perhaps a reference to hailstones, once called hammers in Brittany:

Il pleut et fait solet,

Le diable est à Carteret,

Qui bat sa femme à coup de martet.

It rains and the sun shines,

The Devil is in Carteret,

Beating his wife with a hammer.

In other variants, sun showers are associated with supernatural weddings or domestic scenes: In Upper Brittany, Burgundy, Limousin, Paris: the Devil beats his wife and marries his daughter.

Other traditions involve female or fairy figures:

Finally, in Corsica, the vision is more comical: The fox is making love.

9. Oaths and forbidden acts

In certain regions of France, meteors—especially lightning—are attributed a punitive power, comparable to that of celestial bodies or deities. Thus, they are sometimes called upon in oaths, to seal a commitment or swear vengeance. Thunder becomes here an instrument of divine or infernal justice, and invoking it gives formidable weight to the words spoken.

In Lower Brittany, one does not take lightning lightly. One sometimes hears this dramatic exclamation: “Ann tanfoulftr war n-oul !” (May thunder crush him!). This powerful formula is part of the many “devil’s litanies” in Cornouaille, recited as incantatory curses.

In Provence, the repertoire is just as rich. A few typical examples: “Tron de Dieu!”, “Tron de l’er!”, “Mau tron se ié vau!” (The Devil take me if I go!). These expressions all confirm the ancient connection between thunder, supernatural forces, and popular irreverence.

In Gascogne and Béarn, people swear by: “Pet de périgle!” (Thunderclap). In Wallonia, one exclaims: “Ké l’tonnoir m’accrâs!” (May thunder crush me!). These colorful expressions reinforce the living presence of thunder in everyday language, especially among sailors and peasants.

Among sailors, oaths are often intertwined with the imagery of fire from the sky: “May the fire from heaven strike me down!” In these expressions, the sky becomes judge and executioner, and thunder a destructive agent to which one submits in order to curse, punish, or assert one’s sincerity.

Certain everyday actions can, according to regional beliefs, arouse the wrath of meteors. And sometimes even cause storms or lightning. One must not:

6. Human power over them

While there are rituals, incantations, and magical practices intended to invoke certain atmospheric phenomena, others are considered beyond human reach. These visible and majestic meteors are generally placed under the authority of higher beings, or even deities. Thus, according to traditional beliefs, no mortal can provoke the appearance of:

These phenomena are perceived as autonomous celestial manifestations, beyond the influence of humans, even the most powerful enchanters.

Lightning, for its part, remains under the control of higher entities, but humans can sometimes create conditions that favor it, notably by triggering storms. These storms are said to be capable of:

The witches or storm-makers, very present in rural tales, are often accused of having the ability to invoke bad weather, hence their formidable reputation in the countryside.

The belief in the possibility of stirring the winds or unleashing storms is deeply rooted. These phenomena seem more accessible to human practices. Certain actions—often ritual, sometimes mundane—are reputed to have a direct effect on the wind:

A more marginal idea, now fallen into oblivion, held that certain witches were capable of directing the snow. This belief, notably reported by Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac, seems to have been ignored or abandoned by contemporary oral tradition. This shows that even within meteorological beliefs, some ideas are born, evolve, or disappear over time, according to cultural sensibilities and popular imagination.

7. Tempestaires and wizards

As early as the Middle Ages, the destruction caused by violent winds and especially by hail was attributed to tempestarii, mysterious individuals capable of unleashing the elements… or directing them according to their will.

The Archbishop of Lyon, Agobard, wrote in the 9th century a remarkable treatise, the Traité de Grandine, in which he reported a belief that storms carried their spoils to a celestial realm: Magonia. Hailstones, grains, and rains were said to be transported there aboard airborne ships, guided by blowing spirits. This imaginary geography of the heavens illustrates how medieval humans tried to understand—and control—the wrath of the skies.

Several centuries later, these beliefs remained vivid. In his work Histoire comique des États et Empires de la Lune (1650), Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac imagines a lunar inhabitant recounting that, on Earth, certain witches know: “How to walk in the air and lead armies, hailstorms, snow, rain, and other meteors from one province to another.” This power of celestial travel, as well as the ability to direct storms, confirms that the figure of the meteorological sorcerer was firmly rooted in the mindset of the era.

In 1640, a dramatic weather event shook the region of Dijon (see here):

« ce 14e may 1640 les montaignes de pollonney, malcruy, yseron, St andre,

et pila ont estez couvertes de neige qui a duré jusques au 17 dud[it] quy

n’a faict aucun mal dieu graces sinon aux boys taillis

quy ont estez brulles & les vendredy & sabmedy 13 & 14 juillet

audict an a faict une gellee quy a grandement endomagez les vignes«« La dicte annee 1640 le 16 octobre a faict [une gelée ?]

sy forte quelle a gelle deux doibs despais

et la veille St Simond 27 9bre a nege tout le [jour]

et a dure jusques a la St Andre de la mesme

annee«Témoignages insolites dans les archives du département, Département du Rhône (69) / Rhône-Alpes / Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes

“On the 14th of May 1640, the mountains of Pollonney, Malcruy, Yseron, St. André, and Pila were covered with snow, which lasted until the 17th, causing no harm, thank God, except to the coppice woods, which were burned. And on Friday and Saturday, the 13th and 14th of July of that year, there was a frost that greatly damaged the vineyards."

“That said year 1640, on October 16th, there was a [frost?] so severe that it froze two thick fingers, and on the eve of St. Simon, November 27th, it snowed all day and lasted until St. André of the same year.”

Unusual accounts in the departmental archives, Department of Rhône (69) / Rhône-Alpes / Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes

A late frost and hailstorms ruin the crops. The angry peasants immediately accuse witches of causing this misfortune… and some are thrown into the Ouche, a local river, as a form of expiatory punishment. Even today, in certain French rural areas, these beliefs persist: in Girondine, it is said that some possess the power to summon rain at a precise location, on a day of their choosing—often to harm a neighbor or rival. In Forez, individuals are suspected of rising into the clouds and fog, guiding storms and winds at will.

In the Norman Bocage, tradition holds that the sorcerer walks on the clouds he himself has created, visible at the heart of storms. He is sometimes described as replaced by two black crows, cawing at the forefront of the storm: a scene worthy of a fantastic painting, where the sky becomes a theater for occult forces. And these tales do not stop at the borders of imagination: in the Vosges, two peasant women caught in a storm saw a thick cloud descend to the ground, revealing a woman they recognized perfectly—a neighbor from the village. In Auvergne, an old hunchback woman was seen falling from the clouds in the midst of a violent storm while she performed mysterious gestures.

8. Storm-conducting priests

In the countryside of Berry, Eure-et-Loir, Anjou, and Indre, some believed they could see in the <stronghail-bearing clouds the silhouette of the local priest. Rather than invoking celestial powers to protect their flock, some priests were suspected of manipulating the weather to their advantage. Thus, in Indre, peasants claimed to recognize the priest’s form at the heart of the devastating cloud, like a celestial conductor directing the fall of hailstones.

In the Eure and Orne, priests were believed to use magical formulas taken from the breviary—the liturgical book containing the daily divine office of the clergy—to rise into the air, ascend into the clouds, and bring hail down on the fields of those they wished to punish. This vision of the priest-wizard takes on a spectacular turn in Saintonge, where it was said that priests mastered a magical rope to turn the wind. With this mystical instrument, they could:

Around 1835, in the department of Ain, an amusing yet revealing story circulated: two neighboring priests were reportedly seen high in the sky, arguing over a hail cloud. Each wanted to direct it toward the rival parish, causing a strange meteorological quarrel in the heights. This type of tale clearly shows how human and religious divisions were projected into the sky, where the weather became the arena of a symbolic war between communities.

According to Paul Sébillot, the effectiveness of magico-meteorological rituals often depended on particular locations. Fountains, rivers, or ponds were considered privileged points of contact between the earthly world and natural forces. It is in his work Le Livre des Eaux Douces that the author develops these practices in greater detail, revealing the importance of aquatic sites in weather-related witchcraft.

In the Hautes-Alpes, for example, it was not uncommon for villagers to force their priest to exorcise an impending storm. The priest’s reputation depended on his success: if he managed to calm the tempest, he was celebrated, but if hail or storms repeatedly caused damage, he risked being expelled from the parish. In the Norman Bocage, popular pressure could escalate to threats and violence to compel priests to “charm” the bad weather. In Armagnac, a priest gained a reputation as a sorcerer because no hail fell on his parish for over thirty years, even as threatening clouds often diverted toward neighboring villages.

Priests used various conjurations, sometimes astonishing or even unorthodox. Henri Estienne recounts: “Certain Savoyard priest, having brought the host to stop a storm, and seeing that it could not succeed, threatened to throw it into the mud if it was not stronger than the devil.” (Apologie pour Hérodote, 1580). Around 1835, in a village in Provence, the priest, vested in his ornaments and holding the Blessed Sacrament, would advance under the church’s peristyle and ostentatiously show the host to the clouds to exorcise them.

In the Montagne Noire, it was believed that the priest threw his slipper into the air toward the cloud to prevent hail. A former priest of Germigny (Yonne) would recite the Passion and then make threatening gestures at the clouds. In Provence, some priests threw their hat or shoe at the clouds, sometimes uttering insults to drive them away. This practice may be a survival of an older gesture intended to symbolically strike or repel the malevolent spirit responsible for the storm. A priest in Lower Normandy, nicknamed the “Storm Splitter,” was said to divert storms by turning the tip of his tricorne toward the sky.

In Gironde, certain seers were reputed for their ability to divert storms by blowing from their window or performing conjurations at the boundaries of the communes.

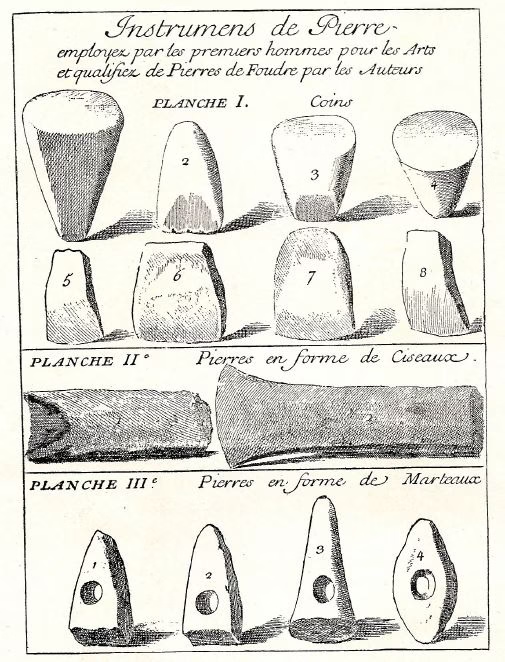

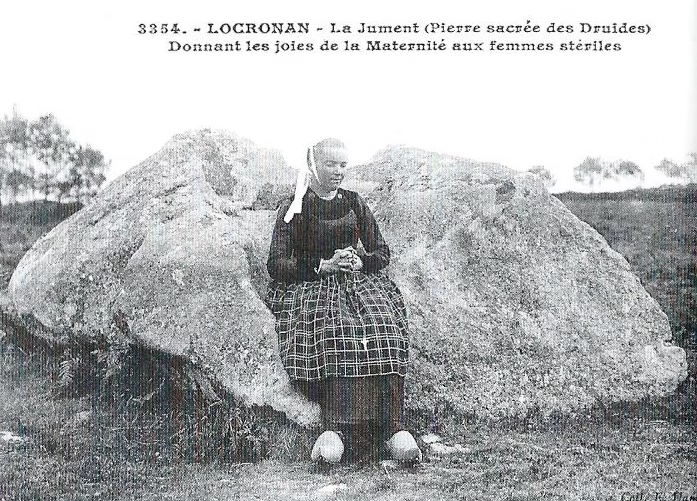

9. The storm, the lightning stones and the iron objects

Among the oldest protective objects are the famous “thunderstones”. These are often split or shaped stones, such as flints, arrowheads, or polished axes, which were believed to have been formed or deposited by lightning itself. They were thought to have the power to protect houses or individuals from thunder. These stones were placed:

Until the mid-19th century, the sailors of Guernsey were not afraid of storms… as long as the “lightning wedge” was hidden in the captain’s cabin. It was a protective object kept on board ships as a substitute for the lightning rod, a symbol of ancient empirical knowledge mixed with ancestral beliefs.

In Upper Brittany, the effectiveness of the thunderstone was enhanced if it was accompanied by a prayer. In the maritime district of Dinan, a simple oral formula was still recited around 1880 when the sky rumbled:

Stone, stone,

Keep me safe from thunder.

In Ille-et-Vilaine, the tradition became Christianized: the stone became a medium for a prayer invoking Saint Barbara (patron saint of firefighters) and Saint Fleur, to ward off thunder and sanctify the object:

Sainte Barbe, sainte Fleur,

À la croix de mon Sauveur,

Quand le tonnerre grondera,

Sainte Barbe nous gardera ;

Par la vertu de cette pierre,

Que je sois gardé du tonnerre.

Saint Barbara, Saint Fleur,

At the cross of my Savior,

When the thunder rumbles,

Saint Barbara will protect us;

By the power of this stone,

May I be kept safe from thunder.

Besides stones, other sharp metal objects were commonly used to protect houses and farms from lightning.

In Brittany, a horseshoe was fixed on the bow of boats, even on those already equipped with lightning rods. In the Basque Country, a axe or a scythe was placed outside the house, edge facing the sky, at the start of a storm. Near Beuvray (Saône-et-Loire), peasants would set up a iron axe, handle against the ground and edge upward, near the threshold, at the first rumbles. In Saint-Gaudens (Haute-Garonne), this custom became partially Christianized: the axe was placed in a plate of holy water, edge facing up. In Gironde, a iron tripod was used in front of the door as a talisman. In Poitou, the three legs of a cooking pot were turned toward the sky in a protective gesture.

10. Embers of the sacred fire

In many regions of France, fragments of the Yule log — or embers from the Saint John’s and Saint Peter’s fires — are carefully kept throughout the year. These pieces of wood, carrying a sacred flame, are considered protective talismans. When a storm approaches, they are taken out of their hiding place while reciting specific formulas to keep the house safe from lightning. This belief is so widespread that it can be considered almost general throughout France.

Even if no written evidence confirms it, it is very plausible that this practice dates long before the Christian era. The bonfires lit at the solstices, in honor of pagan deities, were likely already believed to have the same protective power, passed down from generation to generation.

On the coast of the Côtes-d’Armor, this prayer dedicated to the remnants of the sacred fires was still recited not long ago:

Tison de Saint-Jean et de Saint-Pierre,

Garde-nous du tonnerre ;

Petit tison,

Tu seras orné de pavillon.

Ember of Saint John and Saint Peter,

Keep us safe from thunder;

Little ember,

You will be adorned with a banner.

11. Invocations to Saint Barbara

The most common prayer, with multiple variations, is known throughout France, in both French and regional dialects:

« Sainte Barbe, sainte Fleur,

La couronne de Notre-Seigneur,

Quand le tonnerre tombera,

Sainte Barbe nous gardera. »

“Saint Barbara, Saint Fleur,

The crown of Our Lord,

When the thunder falls,

Saint Barbara will protect us.”

In Upper Brittany, this formula often pairs Saint Fleur with Saint Barbara. They are believed to hold back the thunder with a woolen thread — one white, the other blue. This detail illustrates the richness of local beliefs.

A gwerz Breton (narrative folk song) recounts that the Virgin Mary gave Saint Barbara the choice between ruling over women or thunder. She chose the latter, and since then, she controls lightning with her ring, aiding those who pray to her (Un ami du peuple, Amédée Pigeon, 1896, p. 41). Although some specialists, like Émile Jean Marie Ernault, are unaware of this gwerz, Amédée Pigeon asserts that his translation is faithful to an original Breton text.

In Languedoc, Saint Barbara shares this protective power with other saints, as evidenced by this local invocation:

« Santa Barba, sant’Helena,

Santa Maria Madalena,

Preservas-nous dau fioc et dau tounera. »

(Sainte Barbe, sainte Hélène,

Sainte Marie-Madeleine,

Protégez-nous de la foudre et du tonnerre.)

“Santa Barba, sant’Helena,

Santa Maria Madalena,

Preservas-nous dau fioc et dau tounera.”

(Saint Barbara, Saint Helena,

Saint Mary Magdalene,

Protect us from lightning and thunder.)

In the Pyrenees, devotion to Saint Barbara is very strong. A formula in the local dialect petitions her as follows:

« Ma dauna senta-Barba, / (Madame Sainte Barbe, - Lady Saint Barbara)

De mau periglé Diu nous gardé. » / (De mauvais tonnerre Dieu nous garde. - From evil thunder, may God protect us.)

In Lower Brittany, Saint Barbara is also invoked alone in a prayer asking her to direct the thunder toward the sea to drown it there. In the Perche, it is Saint Catherine who is prayed to stop the devil’s arm when he hurls lightning. In Hainaut, after lighting a candle in honor of Saint Donat, a prayer is recited, beseeching him to divert the storm so it falls “on the water, where there is no boat.” Finally, in the Ardennes and the region of Verviers, Saint Hubert is invoked through traditional prayers to protect against the dangers of thunder, lightning, and the “bad common beast.”

12. Various Observations

For example, in the region of Moncontour in Brittany, while reciting the prayer to Saint Barbara, peasants place a leaf of Palm Bay Laurel on the holy water font and light a blessed candle. In Picardy, the faithful sprinkle holy water with a wooden branch, while in the Vosges, a blessed branch is thrown into the fire, a practice symbolizing purification and protection against lightning.

Lighting a candle, particularly the one for Candlemas, remains a widespread tradition in many regions, even if it is not always accompanied by specific prayers. Other protective gestures, less formal, include placing a Yule log ember in the fire (in Berry and Upper Brittany), or burning a blessed palm, as practiced in the Vosges, the Vivarais, and the Liège region. These customs, blending Christian symbols with popular beliefs, are often performed at key moments of the religious calendar.

In Herve, in the province of Liège, blessed wood is burned in three corners of the room, with the belief that if thunder were to enter, it would exit through the fourth corner, thus avoiding causing damage. In the same region, salt is sprinkled in the four corners of the room as protection against thunder, an ancient practice that illustrates the incorporation of purification symbols into protective rites.

13. Ways to Repel the Storm

In the Yonne, for example, mowers would strike their scythes loudly at the approach of a storm, a gesture believed to drive away lightning. Meanwhile, vineyard workers hung their baskets on branches and struck them with stakes, doubling the blows to ward off danger. In the past, when thunder rumbled, men and women would shout at the top of their lungs, hoping to prevent hail from falling.

In the Albret, storm threats were met with great noise, sometimes including gunshots fired in the direction from which the storm approached, in an attempt to divert it.

In the Montagne Noire, an unusual ritual involves presenting a mirror to the threatening cloud. Seeing itself reflected in the mirror, “so black and so ugly,” the cloud would be frightened and flee, thus protecting the fields from hail.

In several countries, the tradition of firing shots into the air to disperse threatening clouds still persists. It is even said that some “evil beings” hidden in these clouds can be wounded, or even killed, by these shots.

In Eure and Orne, a very peculiar belief persists: it is thought that one can force the “storm priest” to descend to the ground by shooting a blessed bullet at the cloud where he is perched. In Berry, it is common that, following damage caused by hail, peasants report having seen several priests hiding a large number of hailstones in their pockets, as if they were the originators of the storm.

The farmer mentioned by André-Saturnin Morin in his work Le Prêtre et le Sorcier: statistiques de la superstition (1872, p.187), also reports that his neighbor saw a priest perched on a cloud, pouring hail. The neighbor fired a shot into the cloud and saw a crow emerge, pierced by a bullet: the priest, mortally wounded, had transformed into a black bird.

A hunter, believing that witches caused storms, fired at a very dark cloud. At that moment, a shepherd fell at the hunter’s feet: it was he who had made the hail fall to take revenge on a neighbor.

According to Alfred Harou in Folklore de Godarville (Revue des traditions populaires, vol. V, p.381), in several regions it is said that when the sky is very dark, “priests will fall” or “a shower of priests will fall,” particularly in Hainaut. In the 18th century, a similar expression was found:

“The weather is very dark, it will rain priests”

(Philibert-Joseph Leroux, Dictionnaire comique, satyrique, critique, burlesque, libre et proverbial, 1718, Amsterdam).

14. Hail Conjurations and Preventive Measures

In Berry, children still sometimes sing this nursery rhyme to drive away hail:

« La pluie, la grêle, va-t’en par Amboise,

Beau temps joli, viens par ici. »

“Rain, hail, go away through Amboise,

Fair weather, come this way.”

In the Hainaut, a similar, more affectionate formula is recited:

« Y pleut, y grêle, y tonne.

Grand’mère, rochié nos prônes ! »

(Protège nos prunes !)

“It rains, it hails, it thunders.

Grandmother, protect our plums!”

(Protect our plums!)

In the Mentonnais, it is believed that a handful of salt on a child’s back is enough to divert hail. Paradoxically, the hailstones themselves become tools of protection: in the Maine and Gironde, the first fallen grain is collected and plunged into holy water.

A more complex ritual is practiced in the Gers: when hail begins, three hailstones are thrown into the fire; if it continues, seven more are added, and then a shot is fired toward the clouds. The hoped-for result: the storm dissipates.

In several regions of the Midi, women place a medal or a coin with a cross on the threshold to calm hail. In Gironde, the shovel and tongs are arranged in a cross in front of the entrance door.

Some practices are believed to provide long-term protection, even for the entire year: in Franche-Comté, at the first thunder, one must roll on the ground while repeating twice: “I have eaten it.” This action is said to guarantee immunity from lightning until the following year. In the Vosges, peasants plant an egg laid on Good Friday or hang an object on a tree, reciting: “Savior, have mercy on our houses and our fields; protect us from storms through your powerful intercession.” In the Albret, on the morning of Saint George’s Day, one walks around the field before sunrise, while reciting a prayer.

In Franche-Comté, during the Rogation processions, the priest collects stones from the path, attaches small wax crosses to them, and throws them into the fields. They are believed to protect the crops from storms, hail, and torrential rains. They are nicknamed, not without irony, “priest’s manure”.

In the Berry, it is said that fire caused by lightning, called “weather fire”, cannot be extinguished with water. Only certain bell tolls or people who hold the secret of “stopping the fire” can overcome this supernatural blaze.

15. Ways to Ward Off St. Elmo’s Fire

The origin of the names given to St. Elmo’s fire is closely linked to the invocations pronounced at its appearance.

In the Middle Ages and the 17th century, it was frequently called St. Nicholas Fire, a name still used today in Armorican Breton: Tan Sant Nikolas. It was also known as St. Clare Fire, or Tan Santez Klara in modern Breton, because sailors recited a prayer dedicated to this saint when the light appeared on the tips of the masts. In certain regions of Upper Brittany, Saint Clare is still one of the saints invoked during storms, when lightning splits the sky.

In the 19th century, Breton sailors believed they could make St. Elmo’s fire disappear with a simple sign of the cross. This bluish light, which often appeared on the tips of masts or yards, was perceived both as a divine omen and a supernatural manifestation. But in the old navy, the fire was not always seen as benevolent. Some believed it was guided by a sorcerer or even a demon, hence its nickname, “Devil’s Fire”.

Father Georges Fournier, in his work Hydrographie (1667), recounts this astonishing belief:

« Les matelots, sçachant très bien que si c’est quelque sorcier qui leur cause ces algarades se cachant sous la forme de ce globe de feu, il n’est pas pour cela invulnérable, le poursuivent à coups de pique, mille expériences ayant faict connoistre que tout plein de personnes, lesquelles par maléfices et enchantements changeoient de figure, se sont trouvez frappés et mutilés des coups qu’ils ont reçus en telle action. »

“The sailors, knowing very well that if it is some sorcerer causing these disturbances, hiding under the form of this globe of fire, he is not invulnerable, pursue him with pikes, a thousand experiences having shown that many people, who by spells and enchantments changed their appearance, were struck and mutilated by the blows they received in such actions.”

Leave a Reply